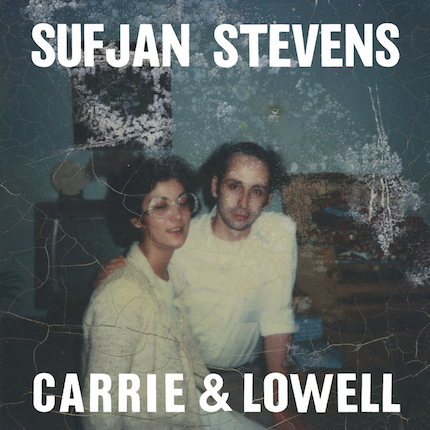

Death and faith in “Carrie & Lowell”

In his last album, Sufjan Stevens explores the loss of his mother in a way that is emotionally devastating.

28 SEPTEMBER 2015 · 10:51 CET

We only have one mother. In his last album, Sufjan Stevens explores the loss of his in a way that is emotionally devastating. She left him, when he was one year old. She had become an alcoholic, drug addict and schizophrenic – today we would say bipolar –, and she suffered from severe depression. She remarried her high-school sweetheart, Lowell, when Sufjan was five years old, but they split up again pretty quickly, when he was six or seven. That was how he and his five brothers ended up growing up with his father and step-mother. He saw his mother again before she died of cancer in 2012.

He got a call from his aunt: “Carrie’s in the ICU, she’s probably not going to live, if you want to see her this is your last chance”. He had a few days with her, in hospital, before she died. After she left them, he would only see her when he went to his grand-parent’s house in Detroit. The only stable times that he had with her were the three summers that they spent in Eugene (Oregon) when she was married to Lowell, at the beginning of the 1980s.

He wants to think that “she was a good mother [...] but she was really sick”. He thinks that “she had nothing but love for us and the best intentions”. He believes that “even as children [...] we were very grateful for the limited time that we had with her." In that sense he says that "we had no delusions or expectations". As an adult, they would meet occasionally for lunch, “but outside of a few letters, we didn’t see each other that much. And I didn’t make an effort to see her".

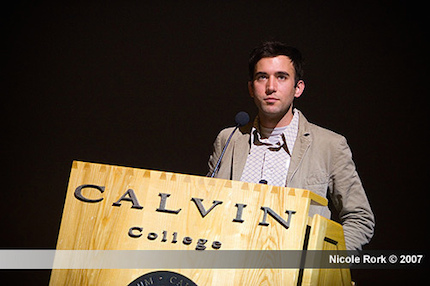

Stevens had a Christian education. He went to the Harbour Light Christian School in Petoskey and studied at a university with roots in Michigan's strong Dutch reformed tradition. There he started to play in a folk-rock band called Marzuki, and he played in a garage band at parties, publishing his first album with his step-father’s record company when he was a student. His life changed when he left for New York, where he now has a studio.

ART AND FAITH

His Christian faith has influenced his music over the last fifteen years although it doesn’t always appear explicitly in his songs. His work is personal and intimate, imprinted by pain. His melancholic tone recalls Elliott Smith's first albums and Paul Simon’s softer ballads. As with all real artists, he is better at asking questions than at giving answers.

Stevens started to draw the attention of Christians in 2004 with his album, “Seven Swans” – although his previous album (Michigan) already included a song that he had written for his friend, the Presbyterian pastor Vito Aiuto–. It contains songs inspired by the Bible – about Abraham and Isaac and the Transfiguration –, with a devotional tone that is expressed in worship songs like “To Be Alone With You”.

This doesn’t mean that he is an evangelical musician. Although he has performed on many occasions at Calvin College of Christian Reformed Church, Stevens goes to an Anglo-Catholic church – an Anglican branch that rejects the liberalism of the North-American Episcopal Church–. He has never had anything to do with so called “Christian music”. He doesn’t record with a company directed to that audience and doesn’t perform in churches, or in other venues on the Christian circuit.

CHRISTIAN MUSIC?

The concept of “Christian music” emerged in America in the middle of the last century. Until then, the divide between the sacred and the secular hadn’t affected the musical work of Christians. Liturgical music was created by and for the church but it wasn’t just music. Some of it was created by Christians, some of it wasn't.

“The Jesus Movement”, in the 1960s, produced music geared towards a younger audience as an expression of Christian worship and witness, bringing together gospel and rock, in what was dubbed “contemporary Christian music”. Jesus music saw the rise of figures such as Larry Norman but, born in such a specific context, the “flower children” movement had its days numbered.

The record companies that were established at that time did not value originality or creative excellence, but saw Christian music as a form of evangelization that spoke to popular culture. The aim was not to produce art, but propaganda. Christians imitated popular songs with as little talent and at the lowest production costs as possible. Songs about Jesus couldn't be distinguished from mainstream love songs. You only needed to swap "Jesus" with "you" to change the connotations.

NOUN OR ADJECTIVE?

In the words of Gregory Thornbury, professor of the King’s College in New York: “Christianity is the greatest of all nouns but the lamest of all adjectives”. After half a century of talking about Christian art, literature or cinema, we have to ask ourselves if there is any sense in using the term as an adjective when all that individuals can do is take others to the cross and follow Christ, regardless of their occupation or personal talent.

Some might say that “Christian songs do exist”. The question is then whether the pain that underlies this album makes for “Christian songs”. Obviously, it isn’t the subject chosen by most of today's “psalmists” – unlike those we find in the Bible–. There are similarities with the music of artists like Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash who, at the time of the “Jesus Music” movement, chose a different path. They made no distinction between their faith and work, their sole aim being to write good songs. Their inspiration was not to convert the world through their music.

“It’s not so much that faith influences us as it lives in us. – Stevens says – In every circumstance (giving a speech or tying my shoes), I am living and moving and being. This absolves me from ever making the embarrassing effort to gratify God (and the church) by imposing religious content on anything I do.”

SOMEWHERE BETWEEN ALREADY AND NOT YET

The Gospel has an important role to play in personal and cultural life. It relates to the whole human experience – what Schaeffer calls the “totality of life”–. Stevens does not deal with religious subjects. In the album before “Carrie & Lowell” he talks about love, sex, death, illness, anxiety and suicide. That is why he attracts a wider audience, regardless of their beliefs. These are human issues that can be of interest to all.

As my friend Brett McCracken says, this is Saturday music. On Good Friday we think about the horror of Christ’s death on the cross and on Sunday we celebrate his resurrection with joy, but Saturday comes in the middle. It is the tension between death and life, loss and victory, suffering and health. That is where we live, like mortal creatures in a decadent world, diseased with sin, while our redemption is ensured by the risen Christ. We will be made new again.

Art is a gift from God to enjoy on Saturday. This speaks even to the Jewish critic George Steiner. In his “Real Presences” he says that “ours is the long day's journey of the Saturday. Between suffering, aloneness, unutterable waste on the one hand and the dream of liberation, of rebirth on the other.” Faced with the inexplicable horror of Friday, “even the greatest art and poetry are almost helpless”.

THE SHADOW OF THE CROSS

For Christian artists, there is a great temptation to move on too rapidly to Sunday. Generally joyful worship music and saccharine sweet evangelical films do not do justice to the Gospel by presenting a world where Christians are always happy. Christ’s humiliation, pain, shame and struggle on the cross cannot be overlooked.

The Jesus who suffered is someone we can relate to because if we experience anything in this world it is pain. “There is no shade in the shadow of the cross,” Stevens sings. In his songs there is no place for clichés and artificial posturing, only for the honesty of being himself. He embraces and imitates the cross.

You gave your body to the lonely

They took your clothes

You gave up a wife and family

You gave your ghost

To be alone with me

You went up on a tree

To be alone with me "

(To Be Alone With You)

“Jesus, I need you, be near me, come shield me”, he sings in “John My Beloved”. He suffers and wishes for something better. Accordingly, his last song has an eschatological theme.

His hope is in heaven: “Lord, touch me with lightning!”. The best art that a Christian can create is there with Christ on his cross, waiting for the coming glory.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Death and faith in “Carrie & Lowell”