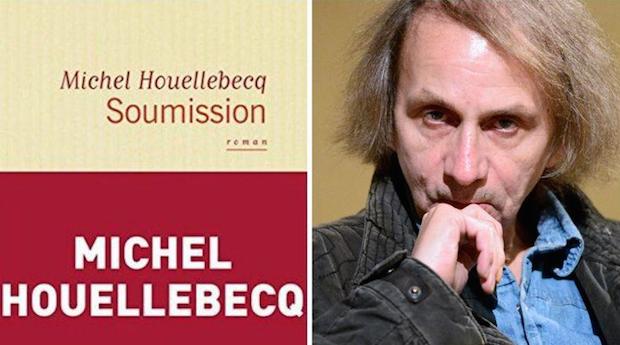

What would happen if Islam came to power in France?

Rather than being a book against Islam, Michel Houellebecq’s “Submission” shines a light on the moral agony of Western cultural decline.

25 NOVEMBER 2015 · 17:38 CET

In Houellebecq’s last novel “Submission”, France has a Muslim president. The book was released on the day of the attacks against “Charlie Hebdo”. However, if there is something that the author cannot be accused of, it is of being an opportunist. Michel Houellebecq is the least politically correct author in Europe. You either love him or you hate him, but he could never be described as predictable – he is always a surprise!

Michel Houellebecq, born in Saint-Pierre (Reunion, France) in 1959, is an indomitable trouble maker. He has so many enemies that he is always accompanied by a bodyguard. Since 7 January 2015, the French Government has ordered that he be accompanied by two plainclothes policemen. There has been so much debate surrounding his book that the prime minister talks about it as if it were a matter of state. You can imagine how many people have thought about it since the recent attacks in Paris.

The book is set in 2022, at a time when France is dominated by fear. The country is immersed in continuous episodes of urban violence that are deliberately hidden from the media. Right and left-wing parties have been overtaken by a new party, the Muslim Brotherhood, led by the young and charismatic Mohammed Ben Abbes, who succeeds in entering into an alliance with the socialist to form a government. Politics and the economy are controlled by secular leaders, but education and values are laid down by Islamists, on the strength of anti-racist arguments.

After one round of elections, cancelled due to electoral fraud, Ben Abbes is elected president. He takes a moderate and tolerant position. He commits himself to protect the three “religions of the Book”, being pretty generous with the Catholic Church. He does however defend patriarchy. He accepts polygamy and requires teachers to teach the Islam. He promotes employment for men and crime begins to disappear. That is the stage on which the Houellebecq’s novel opens.

A COMEBACK FOR RELIGION?

The book’s protagonist, François, is a harmless Sorbonne literature professor, who converts to Catholicism following the example of Huysmans, the nineteenth century author in which he specializes. Like him, he retires to Ligugé Abbey, following a life of dissipation, in which he has tried to bear the tedium of existence with his sexual adventures. Inspired by the Virgin of Rocamadour, he stops having affairs with his students to take up the pilgrimage of faith.

His deacon, Rober Rediger, who was a defender of the Palestinian cause, converts to Islam, going on to become the dean of the university and then minister in Ben Abbes’ government. He finds himself a teenager to be his second wife and lives in a small palace, where the erotic classic “The Story of O” was written. In that novel, the author finds the pleasure of submission portrayed by the Grey novels, while Islam here is portrayed as offering the total submission referred to in the title.

In an interview with The Paris Review, Houellebecq said that the original title of the Novel was “Conversion”. As Auguste Comte argued, part of the author’s conviction is that society cannot live without religion. The author believes that “there is a real need for God and that the return of religion is not a slogan but a reality, and that it is very much on the rise”. Although he flirts with Catholicism, he observes that “in North and South America, Islam has benefited less than the evangelicals”, but “in Africa…you have the two great religious powers on the rise – evangelical Christianity and Islam”.

A WESTERN CRISIS

More than a book against Islam, “Submission” shines a light on the moral agony of Western cultural decline. It provides a mirror image of the existential emptiness of Western decadence. Its ending is heart-breaking because the protagonist fails to find any hope in Catholicism. Houellebecq says that the key scene in the book is the moment when he looks up at the black virgin of Rocamadour and feels her spiritual power for a moment, but then this fades as he walks back to the car park disheartened.

This also appears to have been the authors’ own experience, similar to another French left-winger, Emanuel Carrère, who has also spoken about his disappointment with “the Kingdom”. It is said that the previous pope, Benedict XVI, became a conservative when he saw the revolutionary fervour of the 1968 student protests in Paris, the echoes of which were felt in his Tübengen. By contrast, he admired the confidence in Christianity of European medieval culture, before the Enlightenment separated reason from faith. The question is whether the answer to the West’s crisis is simply to pile on more religion.

Houellebecq represents the confusion felt in Europe today, especially regarding that strange combination in French culture of intellectualism and eroticism. His message is scientific, but just like Carrère, he is also very closely linked to the rock scene. He is passionate about religion, but his novels are full of explicit sex, he gives interviews in a partner-swapping club and his TV appearances are a mixture of long silences and abrupt insults.

THE ATTRACTION OF FAITH

The author of “Submission” says that “I tend to believe when I go to mass, but as soon as I leave, it’s over. So now I avoid it, because the anti-climax is unpleasant. But mass in itself is very convincing; it is one of the most perfect things I know. Funerals are even better, because people talk a lot about life after death and seem to be totally convinced. The truth is that my atheism was not left unscathed by the death of my parents and my dog Clément.”

Despite his scientific education he believes that “in reality, reason is not so clearly opposed to faith. If we look at the scientific community, there are many atheists among biologists but astronomers can be Christians without great difficulty. The reason for this is that the universe is well organized. In the case of living beings, things aren’t quite so clear. They aren’t well organized, and they are a bit repulsive. A mathematician doesn’t have any particular difficulty in believing in God. On the contrary, working with equations goes well with the idea of an order, and therefore of a creator of order.”

However, what interests him is eternal life: “Saint Paul makes this very clear: if Christ is not risen, then our faith is in vain. So that was why Christ came. To promise us that death had been conquered. Love isn’t specific to Christianity. And as for the forgiveness of sin, it is a subject of greater importance for Protestants. In Catholicism, the forgiveness of sin is something more or less automatic. Ego te absolvo, and you are all set.”

LOVE THAT DRIVES OUT FEAR

Houellebecq shows us that religion is not the solution to Man’s problems. Man wants the benefits of faith, without the love and the forgiveness on which it is based. That is why the West’s answer to the threat of Islam cannot be a return to Christendom. We should not fool ourselves. Religion has brought much violence to the world. That is however also the case for atheism and not only Islam produces fanatics. You only need to listen to how some Christians talk about sound doctrine on the subject of sin, family values and homosexuality. Some of them are frankly frightening.

If terrorism shows us a religion of hate and violence, the answer isn’t to indulge in even more resentment and intolerance. Christians have already suffered a lot from fanaticism. Martin Luther King reacted to Afro-American Muslim groups, in favour of violence, with a call for the “creative force of love”. Given that “returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.”

Faced with the strategy of terror, we need the hope that only the love and God can give us in Jesus Christ. John says in his first letter that “there is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear” (1 John 4:18).

As Tim Keller observes, when he encountered racism, Martin Luther King did not call on the churches in the southern States to become more secular, but to return to God’s justice, as seen in the Bible’s prophets. As Keller argues: “Fanatics are not so because they are too committed to the gospel but not committed enough”. That is why we don’t need more religion but more gospel. Nothing else has the power to save us.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - What would happen if Islam came to power in France?