The loneliness of the taxi driver

Scorsese and Schrader’s film revolves around the search for redemption in figures such as Travis, who are buried in an urban inferno, constantly fighting to free themselves of their sins.

29 APRIL 2016 · 09:30 CET

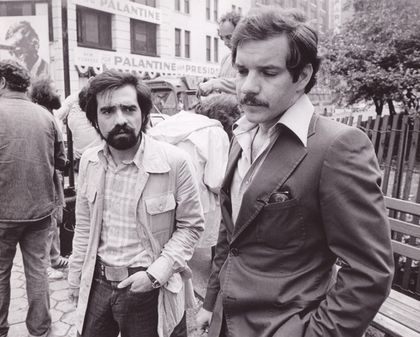

Forty years after the Taxi Driver (1976) film, its re-release reunites the director Martin Scorsese and the screenwriter Paul Schrader, two American film makers who swapped theology for cinema, producing a cult film for the marginalized the world over. Together they presented a restored version of this complex and disturbing film at the Tribeca festival in New York, along with the actors Robert DeNiro, Jodie Foster and Cybill Shepherd.

The professor of the University of Maryland, Robert Kolker, wrote a book for the University of Oxford that describes the films of the 1970s as being part of “a cinema of loneliness”. For him, nothing describes the loneliness of contemporary man better than Taxi Driver. The book cover shows Robert DeNiro walking through the streets of New York, passing by the posters of the long-gone porno theatres that filled the city centre, before the arrival of the video.

There have been many interpretations of the film since it came out in 1976. Some consider it to be a fascist and violent film, understanding it to convey a deeply conservative message. Others see it as a reflection of the tumultuous time that America was going through in the 1970s, providing us with an unusual portrait of the nightmare that unfolded after the decline of the hippie dream. The truth is that the film doesn’t give us any answers, it only raises questions.

Its screenwriter, Paul Schrader, believes that “Travis’ – the character of the taxi driver played by Robert DeNiro – is not a societally imposed loneliness or rage, it's an existential kind of rage.” This harrowing film brings us face to face with the crisis of faith of the Catholic Scorsese and the Protestant Schrader, who abandoned their studies in theology to dedicate themselves to the cinema.

FROM THEOLOGY TO CINEMA

Much ink has been spilt about the failed attempt by Martin Scorsese (1942), a catholic of Italian extraction, to enter the seminary of the Cathedral of the Upper West Side in New York. It appears that, in reality, all that he did was attend a preparatory course at the Seminary for a few months, prior to being expelled. Paul Schrader (1946), comes from a strict Dutch Calvinist family, where he was not allowed to see any films until the age of eighteen. However, his theology course was also only an introductory course at Calvin College in Grand Rapids (Michigan, US), given that he was not in the University’s Seminary. The work of both men is, however, incomprehensible without understanding their Christian background.

“I think that what makes the film so vivid is what has made all my collaborations with Scorsese interesting – says Schrader, who has worked with the Italian-American director on films such as “Raging Bull” and “The last temptation of Christ” – which is that we both have essentially the same moral background - a kind of closed-society Christian morality, though mine is rural and Protestant and his is urban and Catholic; mine is North European and his is South European”. They are both seen as victims of a morality found in the strictest of Christian societies, waging a battle of reason against sin, which represents a blot or offense requiring expiation, to the point of trying to purge it through physical chastisement.

The most common description of Scorsese and Schrader’s work is that of a search for redemption. Their tortured and obsessive characters show us the condition of contemporary man, trapped in his own contradictions. These are figures such as Travis, who are buried in an urban inferno, constantly fighting to free themselves of their sins, in a catharsis of violence and horror.

Schrader’s spiritual preoccupation led him to do a doctoral thesis at the University of California on the transcendental in the films of the Japanese Zen Buddhist Ozu, the French Catholic Jansenist Bresson and the Danish Lutheran Dreyer. The book is dedicated to the evangelical professor Nicholas Wolterstorff, who taught him philosophy at Calvin College, and remained in touch afterwards. When he found himself alone in New York, Schrader entered into a profound crisis, which led him to write Taxi Driver after a stay in hospital, where he had been treated for an ulcer.

LONELINESS AND ALIENATION

The taxi driver played by Robert DeNiro is introduced to the accompaniment of music by the Hitchcock master, Bernard Herrmann, as a veteran of the Vietnam War who suffers from insomnia. In the loneliness of his rickety and solitary apartment, he writes: “Thank God for the rain which has helped wash away the garbage and trash off the sidewalks”. But his hope is that “Someday a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets”, while in his garage he cleans the semen and blood off the backseat of his taxi. In the morning he spends his time wandering through the city and going to porno theatres, while becoming obsessed with weapons.

“At the time I wrote it”, says Schrader, “I was very enamoured of guns, I was very suicidal, I was drinking heavily, I was obsessed with pornography in the way a lonely person is”. For the writer, “all those elements are upfront in the script”. The film maker recalls that “the book I reread just before sitting down to write the script was Sartre's Nausea, and if anything is the model for Taxi Driver, that would be it”.

After pursuing a gorgeous blonde (Cybill Shepherd), who works on a senator’s electoral campaign, Travis’ life becomes a nightmare. She no longer wants to see him, after he takes her to a porno theatre. He then becomes obsessed with saving a young prostitute, barely past childhood (Jodie Foster), who is being exploited by a pimp (played by Harvey Keitel). In his paranoid loneliness, Robert DeNiro’s character enters into a spiral of violence, which ends up in an orgy of blood.

IN SEARCH OF REDEMPTION

Travis gravitates between sin and guilt, in search of redemption. Schrader says that anyone who has been given a deeply Christian upbringing will be interested in the themes of guilt, redemption and salvation. The question for him with regards to the Bible continues to be the same: “How can we atone for our sins?”. He was educated with the Scripture teaching that blood must be spilt, whether it is our own or that of our representative, Jesus Christ. There is no other way for him, of “atoning for sin”. Accordingly, no matter how old it is, the issue of sin, redemption and grace will always be fundamental for him.

Taxi Driver, along with “Hardcore” or “Light Sleeper”, are urban epic stories about sin and evil that contrast with the thirst for purity felt by Travis. All that remains is a trace of existential desolation as desperate as the character of Harvey Keitel in Scorsese’s film Mean Streets or that of Richard Gere in American Gigolo, by Schrader. These are morally disoriented characters in a neon hell, who fight against their very selves, to overcome their misery and find some kind of peace.

However, the only victory over sin comes through the Grace of God. In Christ we “have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of sins, in accordance with the riches of God’s grace” (Ephesians 1:7). The cross is the triumph of grace, which frees us from that terrible solitude to reconcile us with a God, who “in love […] predestined us for adoption to sonship through Jesus Christ” (v. 5). Away from him, there is nothing but desolation.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The loneliness of the taxi driver