God speaks in “Silence”

According to Endô, the Catholic Japanese author whose book is the basis of Scorsese’s new film, “Silence” isn’t about God’s silence, but about how God speaks through silence and trauma.

31 JANUARY 2017 · 12:10 CET

According to Endô – the catholic Japanese author whose book is the basis of Scorsese’s new film –, “Silence” isn’t about God’s silence, but about how God speaks through silence and trauma. Whoever thinks that this is a story for Catholics doesn’t know Scorsese. Endô himself say in the appendix to the second edition of the book, that his “faith is closer to that of protestant Christians”, since he considers it to be something personal between himself and God, that can only be explained by grace.

It has taken almost thirty years for this story to be brought to the cinema by a director who confesses that his life has been “movies and religion. That’s it. Nothing else!”. Born into an Italian-American family, Martin Scorsese’s life has been shaped by the church and cinema. As an asthma sufferer, he couldn’t do sport or play in the streets of New York’s Little Italy as a child, but he enjoyed being an altar boy and watching films.

Both things came to him through the young priest, Francis Principe, who started working in the parish. He would accompany him to the cinema, while at the cathedral’s junior seminar he thought of going out to the Philippines as a missionary.

When he failed to get into the Jesuit university of Fordham, Scorsese enrolled to study cinema in the University of New York, with the idea of returning to the seminar afterwards. Surrounded by the culture of “rock” and after trips to England and the Netherlands, he entered the world of cinema. He says that he is a “frustrated catholic”, because ever since his youth he has experienced continuous tension between his faith and his fascination with sex and violence.

He had a close shave with death in 1978 as a result of drug abuse. Scorsese believes that God answered his prayers in hospital, saving his life. That accounts for the reference to the gospel of John (9:24–26) at the end of “Raging Bull”, about the blind man who recovered his sight.

The words weren’t part of Schrader’s script, who did not understand why he had put them there. He was then 35 years old, but now at 74, his experience makes him present himself as a “Christian with a few doubts”.

There is such theological depth in this story that, compared with films promoted in the Christian world, it contains more doctrinal content in one dialogue than in all of them put together. Even if you have read the book, it is difficult to assimilate the number of ideas that each scene suggests. It is not surprising to see the bewilderment that it produces in many spectators that expect a colourful film in the style of “The Mission” (1986) and instead encounter a dark reflection on grace and apostasy.

THE PASSION OF SCORSESE

Published in 1966, “Silence” was translated into English a number of years later when it garnered the praise of Graham Greene – another writer who converted to Catholicism, but whose doubtful morals caused embarrassment to the Church–, and whose book “The Power and the Glory” has many parallels to this one.

The fascinating interview published in the New York Times with Scorsese, on the nature of his faith, begins with a reading of “Silence” in a Japanese bullet train. He had just filmed “The Last Temptation of Christ” (1988), when the archbishop of the US Episcopal church – in other words Anglican – gave him the book

The Last temptation of Christ, based on the novel by Kazantzakis, adapted by Schrader, and directed by Scorsese, brought together three men with different theological backgrounds – a Greek orthodox, a reformed Christian together and Scorsese, a catholic –, reflecting their battles between the flesh and the spirit and causing furore and protests against the film among Christians.

Demonstrators came out, not only with megaphones and pickets, but set a cinema in Paris on fire. In Greece fines were given for each projection of the film, and in Milan an attempt was made to kidnap Scorsese’s lawyer, while millions of dollars were offered to Universal to destroy the negatives of the film and its copies.

The accusation from Christians of blasphemy led Scorsese to identify himself with the dilemma of apostasy faced by Jesuits in 17th century Japan in the novel “Silence”. Impressed, he acquired the rights for the book, which had already been made into a film in 1971 by Masahiro Shinoda.

The problem was that no one in Hollywood wanted to make the film: bankruptcy and a fatal accident on set made people think that the film was cursed. The only thing that saved it was the money earned with “The Wolf of Wall Street” and a young Mexican catholic producer called Gaston Pavlovich. It was launched modestly. In fact, it didn’t premiere anywhere, except from in a few cinemas in New York and Los Angeles, at the end of the year in order to to qualify for the Oscars.

It is such a personal film, that you could say that it presents the way in which Scorsese wants to see all his work: in the light of his initial religious vocation. When promoting the film in churches, people have talked about it as an example of the persecuted church, when in reality it is about the problem of faith and apostasy, a subject that has divided Christians for centuries. It is no wonder that such a film awakens passions even among Christians. As with many great stories, it can be read in many different ways.

THE HEART OF DARKNESS

In 1633, father Valignano sends two Jesuits from Portugal to Japan to find father Ferreira, who is rumoured to have abandoned the mission that took him into “the heart of darkness”, reminiscent of the 19th century colonising mission in the novel by Conrad that inspired Coppola’s film, “Apocalypse Now”.

We know that we are seeing a journey that will not only show us the darkness of this world that not only rejects the light of Christianity, but also the light in the heart of these envoys, which will soon be subject to doubt and terror.

Another story that finds parallels with Scorsese’s film, is another of the obsession of the “new Hollywood” generation: “The Searchers”. It is the story of the daughter of settlers, who is kidnapped by Indians and who John Wayne sets out to search for with an unexpected result. The film was directed by John Ford, but was remade several times in the 1970s.

The New York critic, Richard Brady, observes that Scorsese is taking up the same theme again in “Silence”. The journey travelled by this generation continues going in the same direction, looking for salvation, when they don’t want to be saved…

The surprising thing is that, for once, the cruelty of the inquisitor is not at the hand of the Church, or in defence of Islam, but at the hand of something so respected in the West as Buddhism. While many naively believe that it is free of all form of intolerance and repression, there is no religion that does not have a history of violence and oppression.

In the first part of the film, the audience is moved by the suffering of persecuted Christianity, but it isn’t long before we start to see some more disturbing elements. If all that is required is to step on an image of Jesus or Mary – the so-called “fumi-e”, which have entered the history of art in Japan –, what does it matter what do with those symbols? Is it so serious to step on them?

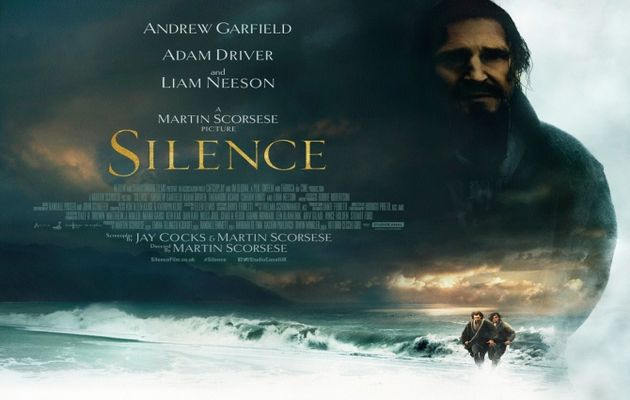

In one of the most revealing comments made by the missionaries played by Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver, one of them says that these persecuted Christians “value these poor signs of faith, more than faith itself”. In order to understand the problem, we need to understand the role of physical reality for a religion as dominated by sacraments as the Roman-Catholic faith, whereby the literal transformation of the host in the Eucharist became one of the main points of contention with the Reformers. The basis of the belief is of course founded in the incarnation, a doctrine which is absent in both Judaism and Islam, as in the rest of Eastern religions.

¿IMAGE OR REALITY?

Garfield – a Jewish actor who has recently had to play other Christian characters, such as a seventh-day Adventists in Mel Gibson’s most recent film – says that in order to play his role he had to go on a 30-day spiritual retreat with a Jesuit named James Martin. He came to the point of “walking, talking, praying and suffering with him”.

This is an image that is seen in each representation of Christ by el Greco, who observes him in his moments of doubt and solitude, hope and fear. The interesting thing is that we see it in the water as a reflection of the missionary’s own face. That is how he sees the deep love of Jesus for him. He looks at him and tells him that he will not abandon him.

What the catholic Endô sees as “closeness to Protestantism”, is not only the personal nature of his faith and the supremacy of grace, but the questioning of the need of those signs that are valued more than faith itself. One of the artists who has most helped us to understand the work of Endô, is Makoto Fujimura, a Japanese painter who was baptised in an evangelical church in 1988, when he was 27 – Endô was baptised when he was 12 when his mother became a Christian in Kobo in 1932, following her divorce–. Fujimura has written several books in English, published by the US Inter-Varsity Press. The book that he dedicated to Endô contains a prologue by Philip Yancey.

THE CHURCH THAT SUFFERS

As a Japanese catholic, the author wonders what it means for Protestants in Spain to be a minority that only accounts for 1% of the population, in a culture that is so defined by its Catholicism, as Japanese society is by Buddhism.

One of the most repeated sentences in this book, is when the inquisitor says that is not the fault of missionaries that Christianity has not put down roots in the land of the rising sun but in the swamp of our world.In countries where the strength of the Church is measured in its social and historical roots, what is the role of this Church, as a minority?

The problem of Christianity in the West is not so different from the situation faced by those Catholics in Japan. In this part of the world, the Church is not used to being a persecuted minority. It continues acting with its dreams of grandeur, as if it could determine the morality of nations for which there are no other values than those recognised by secular society.

When it has as much strength as in the United States, it wages “cultural wars”, such as the one that Scorsese experienced in the 1980s in reaction to the “Last temptation of Christ”, using his film as a symbol. However, it does not know how to handle the marginalisation and contempt that religion faces in Europe. Endô says that it is in that suffering that God speaks to the world.

By giving up his glory, God came to this world to show his power in his weakness. Taking the form of a servant, he humbled himself to the point of accepting the punishment of death on a cross (Philippians 2:7–8), but that which seems to be madness for the world, is the power of salvation for God (1 Corinthians 1:18). “For when I am weak, then I am strong”, says Paul (2 Corinthians 12:10).

Christians may be moved by the torture and martyrdom of the Christians in this story, who in losing their lives, find them (Matthew 16:25), but Endô also shows us that God speaks to us through silence and that the subtlety of a film like this is much stronger than films that try to teach us “values”. Its apologetics do not point to the simple reasoning that “God has not died”, but the strength derived from the fact that God is with us, in the midst of frailty, doubt and suffering.

Pain does not distance us from God, but draws us nearer to Him. Following Jesus is a matter weakness, sacrifice and love. We should seek not persecution, but it may come; it should not be taken with pride or violence, but with the silence of He who “did not open his mouth” (Isaiah 53:7). The fact is that we cannot save the world, because even if we seek to be like Christ, only he can do it. As “Silence” reminds us, we are like Peter and Judas – we both need God’s salvation and that only comes through his grace.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - God speaks in “Silence”