The centenary of the author of ‘A Contract With God’

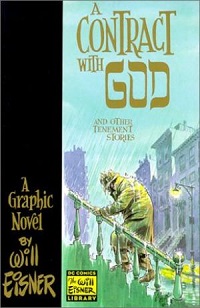

Will Eisner invented the comic for adults in 1978 with a story about the crisis of faith of a Jewish immigrant.

30 MAY 2017 · 08:42 CET

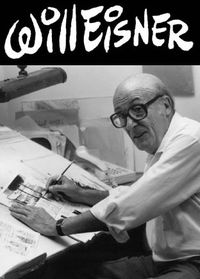

Exhibitions and re-editions have been celebrating the centenary of the creator of the graphic novel, Will Eisner (1917-2005). Thish Jewish cartoonist from New York invented the comic for adults in 1978 with a story about the crisis of faith of an immigrant in A Contract With God.

Until the end of the 1960s, few considered comics as anything other than a form of entertainment for children. Today, however, authors like Eisner have been recognised as artists in their own right. Eisner started out in a studio in New York in the 1930s, working alongside the creators of Spiderman and Batman.

Eisner not only invented the masked detective called The Spirit, but he also wrote manuals on Comics and sequential art and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative. His masterpiece, A Contract with God, is part of the trilogy, Life on Dropsie Avenue.

This book is to the comic what Citizen Kane was to cinema. His main character is an orthodox Jew, who on returning from the funeral of his daughter Rachele, decides that God has failed him…

AN ORTHODOX JEW

“All day the rain poured down on the Bronx without mercy…” The drains flood and water covers the sidewalks. The buildings look as if they are about to be carried off by the whirlpools. It reminds Frimme Hersh of Noah’s Arc, as he splashes his way home: “only the tears of ten thousand weeping angels could cause such a deluge”…

They were blocks of tenement flats, without corridors and with rooms set out like train wagons. They typically provided housing for lowly employees, construction workers, officer clerks and their families.

This story reminds us that, at that time, it wasn’t uncommon for a father to lovingly raise a child, only to lose her, plucked away by an invisible hand, “the hand of God”. Although this is something that happens to many people, Frimme Hersh feels wronged because he had had a long-standing contract with God. What is this contract?

DISAPPOINTED BY GOD?

A Contract with God gives us the story of many Jewish families like that of the cartoonist, who lived through the terrible waves of anti-Semitic pogroms, in Russia, in his case, following the death of Tsar Alexander II in 1882.

As a result, Eisner’s father left from Austria, to make his living in New York by painting sets for the Yiddish theatre. The character in his book escaped from one of these massacres, growing up as an orphan in a village, where he stood out as a kind and helpful boy, doing many good deeds and constantly hearing the words: “God will reward you”…

Out of gratitude to the young man, the villagers save up to send him to America, believing that God is on his side. The rabbi who takes him to the port assures him that God is just and omniscient, since justice is in His hands and God is omniscient.

That night, in a cold forest, he makes a contract with God, written on a stone that he afterwards always carries in his pocket. After being introduced into Hasidic society in New York, he acquires a religious education and pursues a life of good deeds. He believes that he is fulfilling all the clauses of the contract faithfully and reverently.

As a respectable member of the synagogue, Frimme is not surprised by the trust that an anonymous mother places in him by abandoning her daughter on his doorstep. That is why he accepts her as part of his contract with God.

Hersh adopts her and names her after his mother, Rachele. But one day she suddenly falls ill and dies, causing Frimme to cry out to God: “NO! Not to me! You can’t do this…We have a contract!”.

He accuses God of violating his part of the contract. “If God requires that men honor their agreements…then is not God, also, so obligated??”. Furious, in the middle of a storm, he throws the stone out of the window, as the building shakes…

He becomes a ruthless landlord, earning enough to buy the house next door, and then on to build a whole empire. He meets someone, while he makes money from buying and selling buildings as if they were baseball cards.

However, he always refuses to sell his old house. This is how his wife finds out that there is a “black hole” inside him, that neither alcohol or other forms of entertainment can fill.

One afternoon, Hirsch decides to return to the synagogue and meet with all the elders to return the bonds and interests, demanding a new contract with God on the basis that the last one was possibly badly written.

If the elders help him to write it, with all their knowledge of the will of God, in accordance with the law revealed in his Word, he will put up the money to buy the synagogue building.

They therefore draw up a document to help him live in harmony with God. Prepared to begin a new life of charity, that night he reads the document over and over, convinced that it is a genuine contract, that God cannot now violate. That is when a pain in his chest bowls him over. He collapses and breathes his last…

WHAT CAN WE NEGOTIATE?

This story’s epilogue tells us that this time it isn’t just the building that trembles but that a fire destroys all the houses around it. A Jewish orthodox boy behaves heroically, saving many people from the disaster, but shortly afterwards he is surrounded by three other boys who throw stones at him for being Jewish and wearing a funny hat.

As he tries to defend himself by throwing his own stones, he picks up the one on which Hersh wrote his original contact, which that same night he also decides to sign…

Is history repeating itself? As the elders in the synagogue say “all religion [is] a contract between man and God.”. So we are left wondering, did God not hold up his side of the bargain? Does religion stand for nothing?

Eisner is not thought to be a believer, since he asked his second wife, Ann, not to hold a funeral service for him. There is, however, something supernatural about this story, in the trembling building, which is absent from the other stories in this book, which otherwise becomes increasingly sordid.

A few years ago, a book by a New York rabbi, entitled When bad things happen to good people, became a bestseller. It is true that life is full of bad things, but the question is whether we are in fact good people.

Eisner’s character had no doubt about his own righteousness. His good works made him feel sure about himself, but what are good works? Philanthropy, often only covers up great pride; acts through which we try to win God’s favour. But God cannot be bought.

We cannot make a contract with Him, like Hersh did, and think that God is obliged to comply with it. His pact with Israel was bound by grace alone. It had nothing to do with anything that they had done; it was simply the will of God (Deuteronomy 7:7-9).

The problem does not lie in God’s justice, but in our injustice given that “there is no one righteous, not even one” (Romans 3:10). The amazing thing is not therefore that bad things happen to good people, but that God provides so many good things to bad people like us.

That is the marvel of his alliance, by which “if we are faithless, he remains faithful” (2 Timothy 2:13), given that God does not treat us as we deserve. His love and his goodness is shown precisely in the fact that he saved us, “not because of righteous things we had done, but because of his mercy” (Titus 3:4-5).

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The centenary of the author of ‘A Contract With God’