Salinger, the rebel in the rye

Salinger was born in New York to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother. This mixture set Salinger off on a continuous quest for answers from different creeds.

05 JUNE 2018 · 15:38 CET

Few authors have been as mysterious as Salinger. He already eluded us before his death in 2010, which together with the obsession of various criminals with “The Catcher in the Rye” (1951), has made him into somewhat of a legend for various generations of readers who have found in this book a story of initiation. A film now looks at his youth in New York.

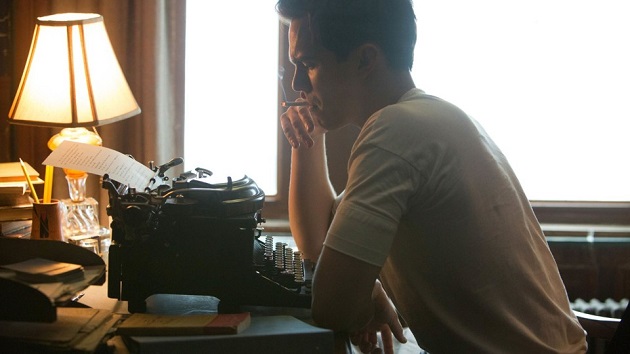

The other night I went to see “Rebel in the Rye” (2017) with my daughter. It is quite a conventional and stylistically indifferent film about an author who was anything but conventional and whose style was unique.

The Director’s experience of Salinger’s novel, age 14, was similar to the feelings that we all had when reading “Catcher in the Rye” as adolescents: “It was the first time I ever read anything in a voice that related to me”, Danny Strong remembers. “It seemed so real, unlike other books I read, which I never thought of as unreal, but they were just stories”.

The film deals with the circumstances in which the book was written in such a monotonous and polite way that it doesn’t allow for any empathy with this tormented boy, nor any identification with his rebellion. It flits through the darkest parts of his life as if they were mine fields, without dealing with the complexity of his darker side. The author of the biography on which the film is based describes his books as love letters to people that Salinger would never have wanted to meet.

LOST IN THE CITY

Salinger is said to have spent ten years writing “Catcher in the Rye” and the rest of his life regretting it. This regret did not only result from the murder of John Lennon, the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan, or the murder of the young television actress Rebecca Schaeffer, all by neurotic people in the 1980s who identified themselves with Holden Caufield. According to certain journalists, it was the trauma of the Second World War and the practice of Vedanta Hinduism that made him turn invisible.

In our teenage years, many of us have identified with the non-conformist Holden Caulfield, who wanders around New York, after being expelled from school, shortly before the Christmas holidays. I must confess that, just like Lennon’s paranoid murderer, I have walked around the places described in Salinger’s novel, one autumn that I lived next to Central Park, near the Dakota building. I didn’t ask myself, as Holden does, where the ducks go when the pond freezes over, but I have felt as perplexed as he does, trying to understand where my life is going.

As in the song by Paul Simon, “A winter's day / in a deep and dark December”, many of us can say with Holden, “I am alone /Gazing from my window to the streets below / On a freshly fallen silent shroud of snow”, since “I've built walls/A fortress deep and mighty / That none may penetrate”, making us feel like “an island” (I Am A Rock, 1965).

A LONER

The main character of Salinger’s novel is a loner. He lives isolated in his own world and doesn’t show his vulnerability. He isn’t closed in on himself because he has had his heart broken but because he harbours a hunger for an intimacy that he has never experienced. In his apparent cynicism, he despises the world and avoids having friends, because he has learnt from the death of his brother that love causes pain.

The directness of the “Catcher in the Rye” draws you in from the first page. That is what makes it mandatory reading in the English secondary school system, despite its evident obscene language and vulgarity. Its disarming honesty makes us forget the obvious. The narrators voice doesn’t talk colloquially, or think aloud, but it transmits the painful sensitivity of an affection-deprived adolescent, who has given up on everything. Behind his coarse language and merciless sarcasm, stands a boy tired of a life he hasn’t yet begun.

“If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them. They're quite touchy about anything like that, especially my father. They're nice and all--I'm not saying that--but they're also touchy as hell. Besides, I'm not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything. I'll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas”… When a book starts like that, how can you not read on?

SPIRITUAL QUEST

Salinger was born in New York to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother – a couple that would not have been very common at the time. The problem was resolved when she converted to Judaism. That did not however stop the break-up of a family with a double heritage. Two religions, two ideas of God and life are not easy to juggle. This mixture set Salinger off on a continuous quest for answers from different creeds.

In the 1940s, the author started to adopt certain Hindu ideas and practices, after declaring himself a “failed zen Buddhist”. In 2000, his daughter told The New York Times that this was only a phase. He later got into scientology, homeopathy and Christian science. Salinger was a true spiritual seeker. He was always interested by religion and his writing reflected that continuous anxiety to find out who God and Jesus are, what love is, and what makes this life worth living.

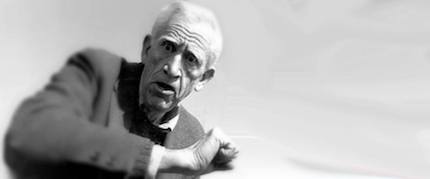

Despite having a certain amount of success in the 1940s – he published various stories in journals of the prestige of The New Yorker –, Salinger became disillusioned with the world of publishing and left Manhattan. He bought a house in New Hampshire, where he lived as a recluse until his death, giving only one interview in 1980. We only have a couple of photographs of him. This has raised speculation regarding his real identity. The most recent image of him is as an old man, lashing out at someone who wanted to take a photograph of him, invading his privacy.

STRANGE FAMILY

After publishing a collection of stories, Salinger put two of them together to form the short novel "Franny and Zooey" (1961), which, although no “Catcher in the Rye”, has received greater literary acclaim. My daughter has studied the characters in detail. They are part of a strange family found in all his stories: the Glass family. They live in an apartment in the Upper East Side of New York – the richest area of Manhattan, stretching from Central Park to East River.

Franny is the youngest daughter of the family, a student and actress, who suffers an emotional and spiritual crisis when she reads “The Pilgrim’s Tale”, an anonymous nineteenth century Russian book based on the Jesus’ Prayer. This oriental orthodox prayer is inspired by verse 10:10-14 of the Gospel according to Luke and goes: "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner”. The repetition of these words and the study of the Greek orthodox book on spirituality, known as "Philokalia", is supposed to help you “never stop praying” (1 Thessalonians 5:17).

Each member of the Glass family seems to be influenced by a different religion. The older brother, following the death of Seymour – a brilliant professor in Columbia University, who committed suicide –, is given the name of Buddy, and teaches Mahayana Buddhism. His younger brother, Walker, is a Carthusian monk and is the twin brother of Walt, who died after the war in occupied Japan. They are followed by Zooey, a television actor influenced by oriental mysticism, who at the age of twelve already sounded like Mary Edy Baker, the founder of Christian scientology.

FRANNY AND ZOOEY

Just like “The Catcher in the Rye”, the action in “Franny and Zooey” covers no more than a couple of days. It portrays Franny as a disenchanted student who is as selfish and “phoney” as the people that so annoy Holden. The book begins with her weekend date with her boyfriend Lane, at the University of Princeton. While they are eating at a restaurant she has a nervous breakdown, which leads them to talk about prayer and the search for spiritual illumination in the Christian Eastern orthodox tradition.

The second part of the book – named after her brother Zooey–, shows Franny in the middle of a crisis, at her parent’s house in Manhattan. In this section there are a lot of references to spiritual texts, which show Salinger’s preoccupation at that time, after various years of studying zen Buddhism and Vedanta Hinduism. He was looking for the renunciation of masters such as Ramakhrishna and Vivekananda. It is in that light that we should understand the famous conclusion of the book which identifies a “fat lady” – whose ugliness and vulgarity represent the audience, for whom they were acting as child prodigies on a radio competition – with Christ.

“Who in the Bible besides Jesus knew–knew–that we’re carrying the Kingdom of Heaven around with us, inside, where we’re all too goddam stupid and sentimental and unimaginative to look?”, Zooey says. “You have to be a son of God to know that kind of stuff”. That is why he upbraids his sister saying that “When you don’t see Jesus for exactly what he was, you miss the whole point of the Jesus Prayer”, which Franny tries to repeat over and over. “If you don’t understand Jesus, you can’t understand his prayer”.

JESUS AND HIS DISCIPLES

Salinger sought God throughout his life but understood that the mystery of divinity revolved around the figure of Jesus. Holden tried praying after the episode with the prostitute in his hotel room, but he can’t. “In the first place, I’m sort of an atheist”, he says, and second, “I like Jesus and all, but I don't care too much for most of the other stuff in the Bible”. He isn’t talking about the Old Testament, but about Jesus’ disciples, who “were all right after Jesus was dead and all, but while He was alive, they were about as much use to Him as a hole in the head”. Because “all they did was keep letting Him down”.

PERPLEXITY AND UNCERTAINTY

Salinger’s constant religious anxiety shows us the paradox of a mysticism that is seeking spiritual peace in an experience of the vision of God through a prayer – as in the case of Franny–, or a philosophy– in the case of Zooey–, but which does not manage to bring peace to the soul. His work shows the intellectual and emotional anxiety that we see in "The Catcher in the Rye”. The characters try to transcend reality but end up blocked in that uncertainty.

In life there are moments in which we feel frankly perplexed. We feel like that perpetual adolescent that Holden represents. That distant attitude that increasingly cuts us off in a seclusion like Salinger’s, who would occasionally seek the affection of women – even though they then betrayed him–, but always felt bitter and disenchanted. His writing reflects a deep despair, because it reflects a spirituality centred in on itself.

FUTURE GRACE

The Bible shows us that the only life that is left for us to live is our future life. The past is no longer in our hands to offer or alter. It is history. All God’s expectations are directed towards the future. Grace is not so much a mere past reality, but also a future one. Believers know that it has brought them “safe thus far” – as the hymn says –, but that it will also lead them home.

As with Franny, we see ourselves as fundamentally weak beings. In our frailty, we don’t find strength within and we ask God to have mercy of us, through Jesus Christ. God’s grace is revealed, however, in our weakness (2 Corinthians 12:9), which shows us God’s love and strengthens us through His Spirit.

Grace is to forget oneself. Our tragedy has been to stray from God and to seek satisfaction in ourselves. The proud spend their time looking down on others, but the way of fighting arrogance is to submit to the sovereignty of God and to trust in his infallible promise to show us his power in our favour (2 Chronicles 16:9).

Both disdain and self-compassion are manifestations of pride, one linked to our success and the other to our suffering. Self-compassion does not look like pride but, in reality, it is born out of a wounded ego. It isn’t a feeling of unworthiness, but rather a desire for one’s worthiness to be recognised.

In the proud person’s heart, anxiety is to the future what self-compassion is to the past. We should therefore apply what it says in 1 Peter 5:6–7 : “Humble yourselves, therefore, under God’s mighty hand, that he may lift you up in due time. Cast all your anxiety on him because he cares for you”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Salinger, the rebel in the rye