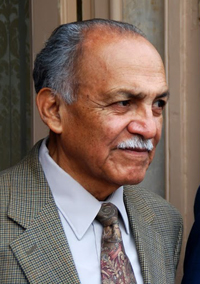

Samuel Escobar: ‘Let’s avoid victimhood, we should learn to live as a mature minority’

The Peruvian theologian gives his perspective on mission: “We must build relationships with secular journalists, which is something that requires time and energy.”

SALAMANCA · 21 APRIL 2015 · 12:35 CET

Samuel Escobar is one of the most distinguished Spanish-speaking theologians and evangelical essayists. He makes us ask ourselves how much the church should be interested about what goes on outside of its walls, because as Dietrich Bonhoeffer said: “The Church is the Church only when it exists for others […] Our own church will have to take the field against the view of hubris, power-worship, envy and humbug, as the roots of all evil. It will have to speak of moderation, purity, trust, loyalty, constancy, patience, humility, contentment, and modesty […]”

Escobar is Professor Emeritus of Missiology at Palmer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania (USA) and a professor at the Protestant School of Theology (UEBE), Madrid. Some of his most known works: Decadencia de la religión (Decline of Religion) (1973), Evangelio y Realidad Social (The Gospel and Social Reality) (1988), Tiempo de misión (Time for Mission) (1999), The New Global Mission (2003), Cómo comprender la misión (How to Understand Missions) (2008) o En busca de Cristo en América Latina (In Search of Christ in Latin America) (2012), among others. He has been a key participant in the three Lausanne Congresses that have been held since 1974. He also formed part of the committee that prepared the Lausanne Covenant.

Evangelical communities –especially in the countries where they are a small minority - need to be proactive, connecting with society. An example are local and national media, according to Escobar: “We must build relationships with journalists, which is something that requires time and energy. We must insist that they fix stereotypes that journalists might have about minorities.”

Escobar answered to questions of Jacqueline Alencar in this interview with Protestante Digital.

Answer. We have to learn to relate causes of the financial crisis to the moral and ethical roots and not to the actions that those roots produce. To do this, we need to develop a specifically evangelical perspective. For example, the passionate defense of abortion that a sector of Spanish society is proposing reveals, in my opinion, a certain moral decline in the understanding of the role of human sexuality. But also the traditional attitude of the Catholic Church, with its opposition to birth control or the celibacy of its clergy, reflects a vision of sexuality that as evangelicals we cannot accept.

The attack on public health and schools reflects an elitist attitude and a poor concept of equality, typical of the traditional Catholic morality rooted in Spanish culture. The Protestant vision of social issues has always been more democratic, less elitist, and closer to the Biblical perspective.

But even more than just learning to raise our voices in protest or in solidarity, we must remember the value that our small daily actions can have, and that through them the evangelical churches can show solidarity with those in need. In time, this could lead to the creation of institutions or procedures that could seek more global answers.

When labor relations are considered, for example, very few people know that the International Labor Organization was originally created by a Swiss Protestant industrialist named Daniel Legrand (1783-1859), who in the beginning of industrial capitalism saw the need for dialogue between workers and employers about justice in their workplace relations.

Q. After 40 years, have you noticed any changes in the world since what we now refer to as the Lausanne Movement began in 1974?

A. I believe that there have been changes, but we must be careful not to attribute them to the Lausanne Movement without sufficient information. I believe, for example, that today’s evangelism style is closer to the Biblical model and to Christ’s example than to sales techniques or religious manipulation. On the other hand, a great number of institutions have been created to channel the potential for social work in the evangelical communities and in cooperation with networks like the Micah Network. It is difficult, however, to measure the impact of these processes.

Q. What has the presence of so many Christians from other latitudes meant for the evangelical Spanish body?

A. I am going to limit myself to discuss Latin American immigration only. On one hand, receiving the immigrants or providing for their material needs has been a challenge to the social consciousness of Spain’s evangelical churches. It seems to me that a large part of these churches has responded quite well, with generosity and without great debate or hesitation. On the other hand, amongst the immigrant believers that have come, their custom of going out to evangelize and utilizing the media, for example, has invigorated many churches and encouraged them to not shut themselves in, which began to happen as a result of their years of persecution and marginalization. In any case, to me, the final outcome seems positive, from the viewpoint of fulfilling the mission.

Q. How much do we lack and what should we do to have more presence and recognition in both the evangelical and secular media outlets?

A. About evangelical media there isn’t much to say, because those outlets take note of the diverse presence of the evangelical churches and generally are open to recognizing those churches that are doing things worthy of being broadcasted.

On the other hand, in the secular media there is a long way to go. We have to learn how to give an account of the churches in a secular language that is accessible to the non-evangelical reader or viewer. We must build relationships with the journalists, which is something that requires time and energy. We must insist that they fix stereotypes that journalists might have about minorities, such as writing “evangelists” instead of “evangelicals” or “mass” instead of “worship or service”.

We must know how to find the most interesting angle on the church’s activities and then highlight it. We must always be alert and know what the right to information implies. All of this requires training for a minority that has lived and continues to live enclosed in its “small world.”

Q. How much more do we lack until we reach having full religious freedom in Spain?

A. Although the application of the religious freedom law needs to be regulated, I believe that there is freedom of expression and practice of personal faith in Spain. There is still much ground to be won, given traditional Catholicism’s majority presence and the power ploys of the bishops. We must always be attentive to the attacks against religious freedom, but also we need to avoid an attitude of “victimhood.” Spanish Protestantism has to learn to live as a mature minority.

Q. Do you think that the churches of today are turning into centers of change, understanding that they have a commitment to society?

A. The contrast between the church being a temple and a centre of change that surrounds your question calls for an explanation that is impossible for me to give at this time. But yes, I see churches here and there that do not limit themselves to the fulfillment of an evangelical ritual each Sunday, but that are trying to respond to various human needs in a creative way, whether that be in communicating the message of Christ, giving attention to its new generations, or in its service to the community.

Q. Does the church need to go through another Reformation?

A. For the time being, evangelical churches need to return to a renewed understanding of the principles of the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century and of the call for spiritual awakening of the 18th and 19th centuries. In the context of our diverse societies, doing so could lead us to a new Reformation. Even better, a creative return to the Biblical source, which has a unique potential for reform.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - europe - Samuel Escobar: ‘Let’s avoid victimhood, we should learn to live as a mature minority’