The Pitfalls of Legalism and Licence

How to overcome two fierce spiritual monsters.

19 MAY 2018 · 11:00 CET

Greek mythology told the story of Scylla and Charybdis, two deadly sea monsters which manoeuvred about on opposite sides of the Strait of Messina.

Sailors who steered too far away from Scylla risked getting devoured by Charybdis whilst those who distanced themselves from the latter were easy prey for the former. How to steer a middle course between the two marine beasts?

The Christian life is likewise beset by two lethal fiends which are by no means mythological namely, legalism on the one hand and antinomianism (or licence) on the other.

What’s the difference?

Legalism is the idea that puts ethics in the place of God’s grace.

Licence is the notion that justifies immorality in the name of God’s grace.

These two opposing principles were both at work in the apostolic church and in the Reformation. So let’s take a closer look at them.

1.- Legalism

Perhaps the best-known example of legalism in the New Testament comes to us from the epistle to the Galatians. The apostle Paul hit out at false teachers in Galatia who were preaching “another Gospel”.

The essence of their “Gospel” went something like this: to be accepted one must believe upon the Son of God and be circumcised. In other words, those who were circumcised could, in some sense, depend on their religious work to justify them eternally before God.

Paul was furious because this type of preaching belittled the cross of Christ. He states in no uncertain terms, “I do not frustrate the grace of God: for if righteousness comes by the law, then Christ is dead in vain” (Galatians 2:21).

The point of Jesus dying, reasons the apostle, was to deliver humanity from the need of self-righteousness. So those who were preaching a new “Gospel” of faith plus circumcision were spitting in the face of Christ.

This same legalistic spirit popped up again at the time of the Reformation. Medieval Catholicism had so undervalued the doctrine of the perfect priesthood of Christ that salvation was ultimately left in the hands of sinners.

How could one be accepted by God? By faith in Christ, of course, but also by fulfilling a long list of religious exercises commanded by the Roman Catholic Church!

Such an oppressive system led the young Augustinian monk Martin Luther to the abyss of desperation.

It was not until the he clearly understood the sufficiency of the atoning work of Christ applied to the soul by faith alone that the German could boast of feeling truly “born again” having entered the “open doors” of the kingdom of heaven.

It should come as no surprise that one of Luther’s major works was his commentary on the epistle to the Galatians. As Paul before him, Luther explained that the legalistic spirit was an outright denial of Christ crucified.

If salvation is Christ plus “anything else”; that “anything else” is of the anti-Christ.

Salvation, then, according to Paul and Luther, is solely in Jesus Christ. It is by no means in us.

2.- Licence

Various New Testament epistles hone in upon the other spiritual brute, namely, licence or antinomianism. Here are but some allusions to it:

- As we be slanderously reported and some affirm that we say: “Let us do evil, that good may come?” (Romans 3:8).

- What shall we say then? Shall we continue in sin that grace may abound? (Romans 6:1).

- They are enemies of the Christ of Christ: whose end is destruction, whose God is their belly, and whose glory is their shame, who mind earthly things (Philippians 3:18-19).

- There are certain men crept in unawares, who were before of old ordained to this condemnation, ungodly men, turning the grace of our God into lasciviousness and denying the only Lord God and our Lord Jesus Christ (Jude 1:4).

The apostles were well aware of impious men sporting the Christian label who abused the grace of God employing it as a pretext to sin.

The message of the New Testament is that the grace of God does not produce a life of disgrace but of obedience to the Lord (Titus 2:11-14).

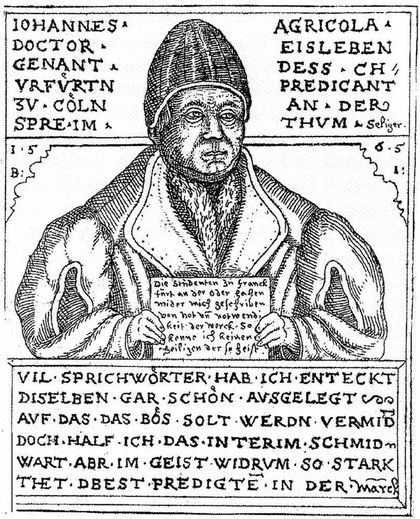

At the time of the Reformation, Luther also had to deal first-hand with the wicked root of licence springing up in the heart of one of his own students, viz., Johannes Agricola. There was such a dispute between the two that Agricola had to leave Wittenberg.

Agricola’s doctrine went something like this: since Christians are entirely justified by the grace of God, they are under no obligation whatsoever to keep the Ten Commandments! Christians are free, therefore, to do as they wish.

Luther and his cohorts were incensed. Although they were convinced that justification is indeed by the free grace of God (and by nothing in sinful humanity), they were similarly persuaded that the saving work of regeneration produced a life of obedience unto the Lord, as the prophet had foretold (Ezekiel 36:26-27).

Both the New Testament and faithful Lutherans preached that saved souls obey God.

Wrapping Up

The only way to steer a middle-course between legalism and licence is recalling the correct relationship between the biblical Gospel and ethics.

To the legalist within, we say: “Christ’s merit is sufficient”.

To the antinomian within, we say: “The Christ who saved me now calls upon me to obey Him”.

The spiritual key, then, is to realize that our obedience is never the cause of our salvation but the consequence of it.

And that truth is a mighty weapon that Scylla and Charybdis can by no means swallow.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Fresh Breeze - The Pitfalls of Legalism and Licence