The death of death

The Christian narrative leaves us remarkably healed from fear and free to enjoy the delights of this world and long for the eternal ones.

15 APRIL 2017 · 19:55 CET

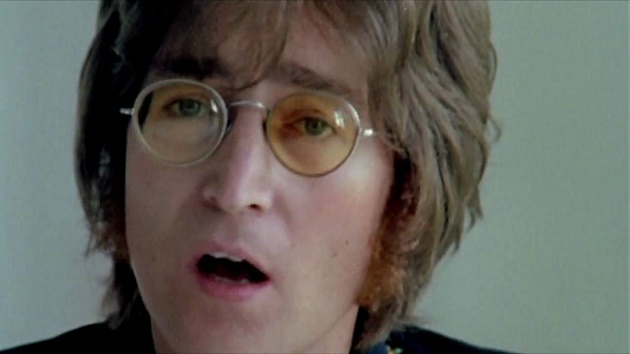

With words that inspired a generation – and that animated a core moment of the Closing Ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics – the Beatles’ most enduring song set people’s hearts aglow with a new vision of the world.

In Imagine, John Lennon asks people to visualize a world with no possessions, greed or hunger; a world with no countries and where everybody lived in peace; a world with nothing to kill or die for. And, as the opening paragraph suggests, the defining feature of such a world is that there would be no hereafter, and people would live for today.

Imagine there’s no heaven

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us only sky

Imagine all the people living for today[1]

In the sixties, this scenario sounded like an impossible utopia, and John Lennon even added the caveat, “you may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one.” Yet, some decades later, possessions, country, hunger and greed indeed continue, but the first paintbrushes of John Lennon’s picture have held firm in our collective imagination: the vast majority of people live indeed with no prospect of a hereafter, with no heaven, hell or some other existence in sight. Many people live actually as if death were an illusion too, and old age and decay a distant future.

This is a very curious development, and it has profound implications for our lives. In the Pulitzer-prize winning The Denial of Death, Ernest Becker analyses this phenomenon, and one of the implications he highlights is the way our immanent understanding of reality impacts the way we love. If death ends everything, if human existence is no more significant than the meaning we concede to it right now, then our hunger for eternity needs other escape valves, and one of then is what Becker calls the Romantic Solution.

[The modern secular person] still had to merge himself with some higher, self-absorbing meaning… If he no longer had God, how was he to do this? One of the first ways that occurred to him, as Rank saw, was the ‘romantic solution.’… The love partner becomes the divine ideal within which to fulfill one’s life…. Man reached for a ‘thou’ when the world-view of the great religious community overseen by God died… After all, what is it that we want when we elevate the love partner to the position of God? We want redemption – nothing less.[2]

The secularization of our lifetimes leads to the sacralization of other things, and one of them is romance. Why else would we sing so many songs and tell ourselves so many stories – our modern-day legends – of romantic quest and fulfillment? Love is how we try to find redemption and meaning; if there is nothing beyond the grave, at least we search for the beauty of timeless yet brief and fragile moments of romance.

But if John Lennon thought the hereafter was crushing with its ominous expectations, our absolute belief in the here–and-now is heavier still. We expect frail moments to carry the full load of human meaning and aspirations, and when they can’t do it, as they inevitably do, we have only nihilism to crash on. Beyond a few memorable moments, life is empty, insignificant, inconsequential, as the Nobel Prize-winning poet Czeslaw Milosz observes in his essay “The Discreet Charms of Nihilism”. If there is nothing after death, we may do as we like.

And now we are witnessing a transformation. A true opium of the people is a belief in nothingness after death – the huge solace of thinking that our betrayals, greed, cowardice, murders are not going to be judged… [but] all religions recognize that our deeds are imperishable.[3]

This would be the moment for some good-ol’ people-bashing. You know, talk of the inevitability of death, of growing up and accepting life, of the foolishness of the Beatles, romantic comedies, and the latest love song. But I find it curious that, actually, the Christian narrative does not ridicule our fear of death. Nor does it deny our desire for both this world and for the eternity we long for. The Christian narrative actually affirms both, and leaves us remarkably healed from fear and free to enjoy the delights of this world and long for the eternal ones.

The Christian solution to our fear of death was captured by the title of a book by one of the good-ol’ Puritans, John Owen: The Death of Death in the Death of Christ. In Christ’s death, Christians believe, death died too. Death died when the Author of Life expired his last breath; death was taken into life, or, as Paul puts it, the mortal was taken into immortality, when Christ offered himself to die in our place so he can infuse us with his eternal life through faith.[4]

The death of Jesus is so significant for Christianity, and the cross became the ultimate Christian symbol, because we believe that it resolved our existential anguish, it atoned for our sins and reconciled us back to God, and gave us a truly splendorous hill from which to reimagine life.

Calvary is our most compelling song – better still than the melody of John Lennon’s Imagine I so like – because here is our reason for this life as well the next one, here is redemption worth living and dying for.

[1] John Lennon, Imagine. Lyrics available at: http://www.lyrics007.com/John%20Lennon%20Lyrics/Imagine%20Lyrics.html

[2] Ernest Becker, quoted in Timothy Keller, Counterfeit Gods (New York: Dutton, 2010), 28.

[3] Czeslaw Milosz, quoted in Timothy Keller, The Reason for God: Faith in an Age of Skepticism (New York: Dutton, 2008), 75.

[4] I Corinthians 15:53

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Culture Making - The death of death