Shaped by the future

The future has a curious power to shape us.

20 OCTOBER 2018 · 17:00 CET

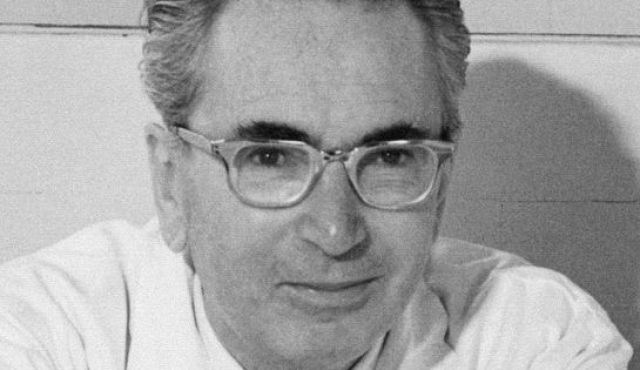

A prisoner like Viktor Frankl learned quickly the signs that someone had given up.

The suffering and humiliation ministered at World War II concentration camps took hold of a person’s soul at last, stripped him of all values and identity and meaning and hopes, and he lost the will to live.

He abandoned himself to the despairing circumstances. Basic acts like smoking a prohibited cigarette or refusing to get dressed in the morning were signs that someone had capitulated. He would die in a few days.

As Frankl observed his inmates giving up on life, he curiously concluded that the moment of surrender consisted not in one’s attitude to his present sufferings. Instead, someone lost his soul when he lost his vision of the future.

The prisoner who had lost faith in the future – his future – was doomed. With his loss of belief in the future, he also lost his spiritual hold; he let himself decline and became subject to mental and spiritual decay… No entreaties, no blows, no threats had any effect. He just lay there, hardly moving.

The experienced hardships were large enough to engulf that person’s sense of present and then his vision of the future: expectations became too dim to remain a guiding candlelight. “Woe to him who saw no more sense in his life, no aim, no purpose, and therefore no point in carrying on. He was soon lost.”[1]

The future has a curious power to shape us. We are what we hope: we live in the future so we can live in the present.

The future arrives before the present, at least for one’s mental sanity, because when we cease to hope, we lose our reason to live..

“It is a peculiarity of man that he can only live by looking to the future – sub specie aeternatatis.”[2] Only when the future is concrete enough does our present acquire its true contours. The strength of our vision of the future, therefore, is the strength by which we engage with life.

Concentration camps were like a severe laboratory to expose human nature. For the people who experienced such harsh life, only a firm future could stand in the face of extreme evil and have the resolve to carry on.

We are creatures of eternity, people with a destiny to fulfill or to ignore, but with a destiny awaiting us nonetheless. Every now and then one of us succumbs to adversity or to easy comforts, and settles.

We let ourselves get enclosed by time and squeezed out by minutes and seconds. We miss the vast plains of eternity, and miss ourselves. We forget to look ahead and we close our eyes.

We nestle in the moment and stop asking ourselves why we exist, or what do we live for, as someone too cosy to care.

Frankl saw a way out. He held steady so he could have a story to tell. He endured blows for the sake of the people who remained peacefully outside, to share lessons only pain could teach.

And his advice to prisoners in concentration camps then and urbanites in comfy couches now remains as fresh as the earliest news of liberty.

What was really needed was a fundamental change in our attitude toward life. We had to learn ourselves and, furthermore, we had to teach the despairing men, that it did not really matter what we expect from life, but rather what life expected from us. We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life, and instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned.[3]

[1] Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning (New York: Washington Square Press, 1984), 95, 98.

[2] Ibid., 94

[3] Ibid., 98.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Culture Making - Shaped by the future