The environmental causes of the Syrian crisis

The huge investment in agriculture transformed the semi-arid Al Badia region into fields of maize and cotton, by means of subsidies to farmers and the drilling of thousands of wells. This added to the pressure on water resources.

08 OCTOBER 2015 · 10:51 CET

It is easy to think that the crisis of refugees from Syria and neighbouring countries, which is now beginning to affect us directly, has its origins only in the ethnic and political conflicts in this part of the Middle East.

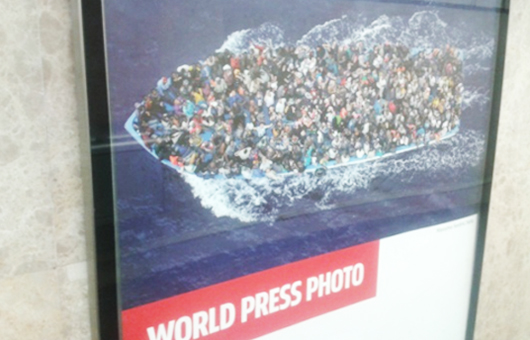

The media has bombarded us daily with images, first of the military conflict and the barbaric scenes provoked by extremist groups such as Daesh (ISIS), to then replace them – although cities keep falling and atrocities continue to occur, producing even more refugees - with images of those who are attempting to enter the ‘Promised Land’ of Western Europe after a long and exhausting journey through a number of countries.

The country of Syria is characterised principally by semi arid steppe lands (about 55% of its territory, called Al Badia), dry plains that receive rain infrequently and irregularly, with livestock farming as the main economic activity.

In the last few decades the Assad government had invested hugely in the modernization and mechanization of agriculture and livestock farming. Thousands of wells were dug to tap underground aquifers. Little by little this unsustainable exploitation of the hydrological resources resulted in a fall in the underground water level in the rocks, leading to a decline in river discharge, the latter already seriously affected by the increase in water use and abstraction upstream in Turkey.

Environmental crises do not normally appear in the media until the situation has become catastrophic. The impact is gradual, but the long term effect can be even more devastating than a natural disaster. One only has to remember the great Sahel Drought that affected a large tract of terrain across northern Africa from Senegal to Ethiopia between 1968 and 1973.

In the Middle East the focus was on the armed conflict, the arab-israeli tensions in Palestine, weapons of mass destruction and the Arab Spring. Syria was considered by international experts in risk analysis as a country with a limited probability of suffering internal revolt. The experts focused only the country’s urban problems, related to sectarian and ethnic differences.

The huge investment in agriculture since the 1960’s transformed the semi-arid Al Badia region into fields of maize and cotton, by means of subsidies to farmers and the drilling of thousands of wells (from 135,000 in 1999 to 213,000 en 2007). Livestock numbers increased from 2,6 to nearly 12 million. Rapid population (2.6%) and urban growth added to this pressure on water resources. This type of overexploitation of water resources was already well documented in other parts of the world, such as in the former Soviet states and in the American West.

In many dry areas the groundwater is ‘fossil’, having accumulated in wetter periods thousands of years ago, only recharging in the ‘wetter’ years, and the water level drops rapidly with heavy water use. Wells are dug deeper, and apparently no change occurs, until the whole system collapses. This is what hydrologists, geographers and geologists are auguring for the American West today.

A rapid change of the balance between the supply and demand of water, such as in a severe drought, leads to rivers running dry, artificial reservoirs and desertification accelerates. There is little margin for more imbalance, and with the onset of other problems, of a political and social nature, a disaster is inevitable.

Syria experienced the worst drought in decades between 2006 a 2011: rainfall was lower than that necessary to maintain dryland agriculture, and the groundwater reserves were almost dry. 85% of the livestock died and 2 to 3 million farmers faced extreme poverty in a matter of months. Despite this the response of the national government was negligible. The Ba’ath party had come to power years before on a wave of great popular support, promising land redistribution, but at the turn of the millenium lack of sensitivity and support by the national government, the alliances of powerful urban families related to the government, the corrupt practices of businessmen and traders and the nepotism within the military hierarchy excluded the farmers, seen as an inferior ‘caste’, who found themselves having no other choice but to emigrate to the main cities in Syria, changing rural for urban misery.

The cities, already crowded with hundreds of thousands of poor Palestinian and Iraqi refugees, could no longer cope, suffering already from the lack of work and a decaying and insufficient infrastructure. It was not surprising then that it only needed a small spark to ignite the revolt against Assad: Starting in Daraa, one of the cities which had suffered a huge influx of refugees, the flame spread rapidly to towns with similar characteristics. Poor management and sensitivity could only lead to the situation getting out of hand.

The drought was not the only cause of the present crisis, but we can see that it was a major factor in the origins of the conflict.

Where selfishness, injustice, and lack of solidarity reigns, the social differences in areas like the Middle East, where water is a major essential resource, increase rapidly, creating social and political instability. For years this region has been an area of continual conflict due to the converging interests of the countries with high energy consumption due to its abundance in another underground resource, petroleum. But analysts today see the conflicts over water supply as the principal causes of instability, open conflict between neighbouring states, and massive population displacement.

The repercussions of the Syrian crisis are not now limited to the surrounding states. The ‘Promised Land’ of Europe is being challenged seriously, for perhaps the first time in decades, with a crisis that questions it values, its unity and the very stability and comfort that its inhabitants have taken for granted so easily. The problems of the Syrians have always been our problems. In a globalized world, what happens in one part of the globe has serious repercussions in other regions.

A Christian response must necessarily always reflect the values of a greater kingdom than those of this world. Love, compassion, solidarity, sacrifice, and a trust in the King of the eternal kingdom, whose promised do not fail, and who holds the destinies of the nations in His hands, are the values that His people must show in these times of crisis. Christians must not be dragged into the current mindset, one of fear and entrenchment that prevails in the societies that just see social and political changes in the light of the comfort they may gain or lose. The challenge of the disciples of Jesus in Europe today is to take seriously Christ’s words, commands and view of the world. Are we prepared to stand up and be counted?

Michael Wickham is a teacher. He has a degree in Geography (Oxford).

Sources:

“Syria’s war has environmental origins”, Global Risk Insights: http://globalriskinsights.com/2013/09/syrias-civil-war-has-environmental-origins/

“Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria, Peter H. Gleick, Pacific Institute, Oakland, California, http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Features - The environmental causes of the Syrian crisis