Caesar: Cash is king

Money is one of the tools of that centralised authority, open to all the abuses that control over its supply enables. The coin in Jesus’ hand was the perfect example of those dangers.

24 MARCH 2016 · 18:05 CET

Caesar is the most influential character never seen in the New Testament. The Roman emperor does not make a personal appearance in the accounts of the disciples and the early Church, but he stands behind the scenes of almost everything that occurs. He can be considered Jesus’ opposite number, the personification of all that is evil and wrong with the world – a theme most clearly seen in Revelation with its imagery of Babylon (Rome) and the Antichrist.

There were several Caesars in the century or so covered by the books of the New Testament, and at no point is a good word spoken of any of them. There was Augustus, who ordered the census of Luke 2:1, and who ruled for 40 years until 14 AD. His successor, Tiberius – mentioned in Luke 3:1 in the backdrop to John the Baptist’s ministry – reigned until 37 AD and was therefore emperor throughout Jesus’ ministry. The cruel and insane Caligula’s brief reign followed, then in 41 AD Claudius came to power, expelling all the Jews from Rome – probably in 51 or 52 AD (Acts 18:2). Then there was Nero, who brutally persecuted the new sect known as Christians, and whose reign saw the start of the Romano-Jewish war that ended in the Fall of Jerusalem. The Greek word for ‘calculating’ the number of the Beast in Revelation 13:18 is a specific method for which Nero’s name is one of its solutions.

But all of these characters are conflated into a single shadowy and dark force pulling the strings of the Roman Empire. Individual identities barely matter; like the Dread Pirate Roberts or Dr Who, there is always a new Caesar. However, perhaps it is not quite fair to say Caesar is never seen in the New Testament. There is one occasion when Caesar’s face does make an appearance:

‘Then the Pharisees went out and laid plans to trap him in his words. They sent their disciples to him along with the Herodians. “Teacher,” they said, “we know that you are a man of integrity and that you teach the way of God in accordance with the truth. You aren’t swayed by others, because you pay no attention to who they are. Tell us then, what is your opinion? Is it right to pay the imperial tax to Caesar or not?”

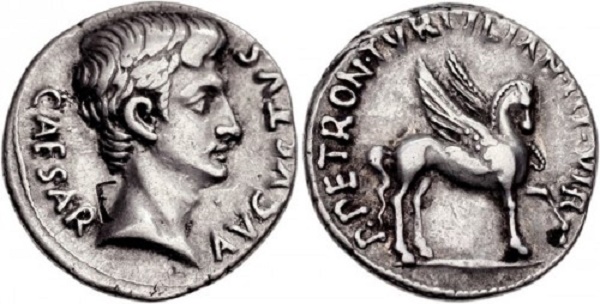

‘But Jesus, knowing their evil intent, said, “You hypocrites, why are you trying to trap me? Show me the coin used for paying the tax.” They brought him a denarius, and he asked them, “Whose image is this? And whose inscription?” “Caesar’s,” they replied. Then he said to them, “So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.” When they heard this, they were amazed. So they left him and went away.’ (Matthew 22:15-22)

Jesus’ response – typically ambiguous and raising more questions than it answers – opens a discussion about the nature of power and our relationship to it.

PAGAN RULE

The silver denarius bore the head of Tiberius, emperor since Jesus’ teenage years. Behind the Pharisees’ question lies the Pythonesque ‘What have the Romans ever done for us?’ Behind Jesus’ response is the catalogue of public services and protections enjoyed by the Jews. It is Caesar’s coin, both produced by and funding Caesar’s state machinery, so Caesar has a legitimate claim to it.

But the remark is, like the coin, double-sided. What does belong to Caesar? What belongs to God – and what happens when the two claims come into conflict?

Jesus’ listeners likely recognised that the answer to those implicit questions lay on the same coin. The Roman denarius bore the likeness of Caesar. Thus the demonstration of ownership was also a direct breach of the second commandment, ‘You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below.’ (Exodus 20:4) The denarius was the most common coin used in Jesus’ time, the standard wage for a day of labour (Matthew 20:2). It would have been a constant reminder of pagan Roman rule and infringements on the Jews’ religious freedom – raising the same uncomfortable question that the Pharisees asked every time it changed hands.

Moving beyond the most obvious implications, there is a wealth of significance just under the surface of this episode. The small coin symbolises not just Caesar, but every government and human power of any kind. As explored in previous Engage articles, the Jews had had long and painful experience with centralised authority. It was ingrained upon their collective memory thanks to their years as slaves in Egypt, and contact with numerous belligerent nations in the centuries afterwards. As a result, Israel’s own structures of power were to be more dispersed and less prone to abuse (Deuteronomy 17, 1 Samuel 8:11-20).

‘HE WHOSE COIN IS CURRENT IS LORD OF THE LAND’

Money is one of the tools of that centralised authority, open to all the abuses that control over its supply enables. The coin in Jesus’ hand was the perfect example of those dangers.

The denarius was originally minted towards the end of the 3rd century BC. It was made from almost pure silver and weighed roughly 4.5 grams. In the time of Augustus, a few years before Jesus’ conversation, its silver content had been reduced by around 13 percent. This meant Augustus could mint coins with the same face value, but that cost less in silver to create – a discrepancy that represented an attractive source of income to him and subsequent emperors.

Before about the 7th century BC, money usually took the form of pieces of precious metals, typically silver for everyday commerce. The purity of these could be checked on a touchstone and they would be weighed out at the point of transaction. It was dependent on standard weights, but took place firmly in the hands of the end users of money. Coins were probably only introduced to the Israelites in the 6th century, after their return from Babylon. With this convenience also came debasement for personal and political gain. The state had a monopoly on this process, and exercised it to an extent impossible for an ordinary merchant or customer. Centralising money creation resulted, as night follows day, in the state extracting wealth from its people.

Debasement and inflation was only one of the abuses to which the Roman Empire subjected its citizens, but it was part of an overall package of evils by which those in power controlled their subjects. The denarius was the closest that most Jews would ever get to Caesar. It was not a ringing endorsement for his rule. Jesus’ answer could then also be interpreted as something like, ‘Caesar has defrauded you and lied to you. He forces you to handle idolatrous images of him every day. What does such a man deserve?’

REAL POWER

Finally, the exchange over the denarius highlights the different approaches to power embodied by Jesus, on the one hand, and earthly authority on the other. ‘Then Jesus said to his disciples, “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it. What good will it be for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul? Or what can anyone give in exchange for their soul?’ (Matthew 16:24-26) Although this is presumably meant figuratively, there was only one person who could claim to have gained the whole world: Caesar.

The idea of voluntarily giving up power, of course, would have been anathema to Caesar. Rome was the global superpower of its day, a sprawling, expanding empire kept in check by a huge military machine, funded by oppressive taxation and an ever-more debased currency. But, as Paul writes, ‘the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength.’ (1 Corinthians 1:25)

APPLICATION

Jesus’ exchange with the Pharisees over a denarius suggests several areas of application for us.

1. Hold money lightly. Inflation is an earthly reminder of what money is really worth in the long-term: nothing. In the long run, as Keynes said, we’re all dead. ‘Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven.’ (Matthew 6:19-20)

2. Identify the ‘Romes’ in your life. Are there institutions, organisations, structures of power, and so on, in your life, which exert an undue and unwelcome influence on you, simply because they set the rules for the way you engage with the world? It might be own our monetary system, your employment, even the consumer culture we take in through different media. How can we reduce their influence on us?

3. Rethink ‘leadership’. Much has been written about Christian Leadership, though this is often conventional management/leadership techniques with a thin Christian gloss. The contrast between Jesus’ and Caesar’s approaches to leadership suggests that it should involve giving up power rather than accumulating it – a difficult challenge for those in any position of authority or leadership in any sphere of life, large or small.

Guy Brandon is Research Head at the Jubilee Centre (Cambridge).

This article was republished with the permission of the Jubilee Centre.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Jubilee Centre - Caesar: Cash is king