Way to heaven

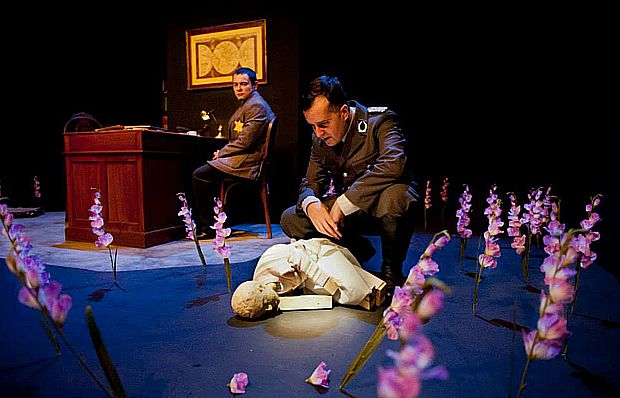

The main character of Himmelweg is a Red Cross worker who is an accessory to manipulating History, by covering up the truth of what really happened in a Nazi concentration camp.

22 FEBRUARY 2017 · 09:29 CET

Juan Mayorga is an oddity in Spanish theatre. With an academic background in mathematics and philosophy, his theatre is one of ideas, closer to the Central European school than to his own Spanish roots. The play for which he was awarded the Enrique Llovet prize, Himmelweg (Way to heaven) has returned to theatres is Spain, this time presenting Raimon Molins in the Fernán Gomez theatre in Madrid. The subject of the play, the Holocaust, is one that is rarely touched upon in Spain. The main character is a Red Cross worker who is an accessory to manipulating History, by covering up the truth of what really happened in a Nazi concentration camp.

The playwright was born in Madrid in 1965 and made a name for himself when he received the Born theatre award for his play “Love letters to Stalin”, first staged by the Spanish National Dramatic Centre, in 1999. His play surprised many by its criticism of communism, but also by its intellectual stance at a time that was all about entertainment and spectacle. His attention to words has also made him one of the most published playwrights in recent years, first with “El jardín quemado” (The Burned Garden); then with “El traductor de Blumenberg” (The translator of Blumenberg), or “El sueño de Ginebra” (The Dream of Geneva), a play that has featured a lot on alternative circuits, as well as “Animales nocturnos” (Nocturnal Animals).

Since then, Mayorga has not stopped winning prizes, including the 1997 edition of the prestigious Spanish Calderón de la Barca prize for this play “Más ceniza” (More ashes). The publishing house Anthropos has also published the philosophy thesis that he wrote in Germany, “Revolución conservadora y conservación revolucionaria, política y memoria en Walter Benjamin” (Conservative Revolution and Revolutionary Conservation: Politics and Memory in Walter Benjamin).

Having made some incursions into comedy with “El Gordo y el Flaco” (The fat man and the thin man) and “La boda de Alejandro y Ana” (The wedding of Alejandro and Ana), he has also made his own recreation of the poetry of the Spanish poet Rafael Alberti. This was directed by Helena Pimenta, who is known for her adaptations of Shakespeare for the Spanish Society for Cultural Commemorations. The play was based on one of Alberti’s lesser known books, “Sobre los ángeles” (Concerning the Angels), written between 1927 and 1928, in the midst of a deep personal crisis.

THE HOLOCAUST

The play that Gerardo Vera chose to open his term in office at the head of the National Drama Centre, takes place in 1942, in the midst of the extermination of Jews by Nazi Germany. For Mayorga, “Himmelweg (Way to Heaven)”, acts as something more than a historical play that addresses something as specific as the Holocaust: it investigates the essential problem of truth. Mayorga says that he uses it to refer to “events, regardless of whether they are in a fiction or based on a time-specific event”.

“Himmelweg” is about a Red Cross worker who wants to help people. Appointed to be a neutral observer, he enters a concentration camp, and although he feels that something is amiss, he submits a positive report of what he has seen. The lynchpin is a ramp, leading to some kind of hangar. They tell him that it goes to the infirmary, but all the Jews call it the way to heaven, because no one ever comes back down it. If he had had the courage to go up the ramp, and open that door, he would have discovered the great lie that the Nazis were covering up.

Mayorga identifies himself with that character, who wants to help, but who lacks the courage to open doors. He trusts in what others tell and show him. That is why he fails to see that the way to heaven is actually a door into hell.

LOOKING WITHOUT SEEING

The main character in the play constantly finds himself at a crossroads. “It is about a man who is like almost everyone I know”, Mayorga says. His desire to help is sincere; he is a charitable man who is horrified by other people’s pain”. And “yet, as with almost everyone I know, he is not strong enough to see with his own eyes and put things into his own words, making do with the images fed to him by others”. For this reason, Mayorga believes that “art should open doors, and look into the eyes”. And in this sense, art and philosophy coincide in their objective, their mission being truth. That is why Paul Klee said that art does not imitate reality but rather reveals it. Reality is not something obvious, but something that we have to make an effort to see. But what can we do to discover that truth?

The Nazi commander in Himmelweg is a cultivated man who reads Calderón and Shakespeare, and is actually more interested in books than in people. He represents “the enlightened naïve dream”, says Mayorga, “that culture would tame the jungle and save humans from brutality”. But the truth is that it “turned into a nightmare, and we have come to realise that culture and brutality are compatible, and that a certain type of culture may be actually incubating brutality”. This is the question that Adorno asks: how can you listen to music by Mahler in the morning and torture by night? The author is trying to find a critical culture that mistrusts even itself. Here, education is forged through questions and mistrust.

This play is a master piece that launches a full-blown investigation into the evil that begins with a relentless and anguished confession, and ends with a terrible journey towards death. When the main character returns to that den of iniquity, he finds that a forest has been planted in its place. Wandering through it he goes over the whole thing, overwhelmed by a bottomless feeling of guilt, with no choice but to see himself as an accomplice in the horror. This heart-rendering introduction is delivered through a long and painful monologue. The action then moves to the days of preparation to create that false citadel, got up by the Nazi commander, who covers up the real devastation with the help of the Jewish collaborator Gottfried.

THE PROBLEM OF EVIL

Juan Mayorga is a member of the group directed by the philosopher Reyes Mate, called “Judaism, a forgotten tradition”, which is not only interested in Jewish perspectives on the world, but in the meaning of philosophy after the Holocaust. The biblical worldview on which Judaeo-Christian thinking is based is no longer particularly popular, as it is based on a radical conception of the evil of humanity, while it is the belief of the Enlightenment in the innate goodness of humanity that led us to the nightmare of the Holocaust. Our problem is not a lack of science or knowledge, as the philosophers of the Enlightenment believed, but it is that we do not want to face up to the reality of the perversion that lives in our own hearts.

That total depravation that is present in all human beings is what the Bible calls sin. That is our main problem, even though we try to find excuses at every turn, blaming others or our circumstances. We do not want to see ourselves for who we really are. That is why we shut down any sense of guilt, imagining that, at the end of the day, we are not as bad as all that. But our problem isn’t a superficial reality, like a simple layer of dirt on our car window. It is something that we cannot get rid of, a corruption that accompanies us from the moment that we come into this world and that affects our whole lives.

Jesus came to the world to save sinners like us, of whom, Paul says, that he is the foremost (1 Timothy 1:15). Sin is something real and objective, that stands between me and my Creator. The God who governs this universe is not an impersonal energy. He is a moral being, a holy judge, who we have offended.

What are we going to do with our guilt? Are we going to continue hiding it hypocritically? The Bible teaches us a better way, which is to face up to it. We should approach God as the people that we really are. “If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves and truth is not in us”. But “if we confess our sins, He is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:8-9). His love and compassion are never failing.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Way to heaven