The monster within me

The monsters and ghosts in “The Shining” are real, but they live within us.

22 MARCH 2017 · 10:12 CET

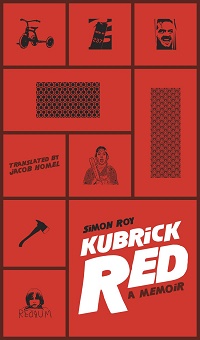

“You can move away from a stranger. You can’t move away from yourself”. The monsters and ghosts in “The Shining” are both real, but they live within us. The obsession for the novel by Stephen King – taken to the cinema by Stanley Kubrick – has made some people discover their darker side, as the literature professor Simon Roy observes in his memoir “Kubrick Red”.

With “The Shining” (1977), King went from being the “king of horror” to being the author of “the great American novel”. Although he was disregarded at the beginning of the century by Harold Bloom, the author of the “Western Canon”, when he received the US National Book Foundation Award in 2003, prestigious media outlets such as the New Yorker and the New York Times Book Review suddenly began to recognise his work. In a parallel situation, Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” (1958) would never have come to be considered the best film in the history of cinema, over “Citizen Kane” (1941), had it not been for a handful of French critics.

It was thanks to my friend Julio Martinez that I discovered the more sentimental King of nostalgic stories about lost childhoods. As in the films by Hitchcock – the “Master of Suspense” and possibly the only name that I can think of when I’m asked who my favourite director is–, the truth is that I would not be able to say which of King’s books or films is my favourite: among his novel “Dead Zone”, “22/11/63”, “It”, “The Shining”, “Joyland”, and his films “The Shawshanks Redemption” (Rita Hayward and Shawshanks Redemption), “Dead Zone”, “The Green Mile”, “Stay By Me” or “The Shining”.

THE BOOK OR THE FILM?

As Rodrigo Fresán says, three types of people watch Kubrick’s “The Shining” (1980): those who have only seen the film; those who have read the book and watch out for the changes; and those like myself or Roy who “went from the colourful darkness of the cinema to seek refuge in the black and white of the words” that cover the corridors of hotel Overlook. I am becoming increasingly convinced that there is no sense in the hackneyed question about whether the book or the film is better. A book is not a film and vice versa. They are two different things.

King hates Kubrick’s film because it is not his book. What few people know is that it isn’t an original story by King. “The Shining” was born from a short story that the late author of the “Red Badge of Courage”, Stephen Crane (1871–1900), published a few months before dying at the age of 28. “The Blue Hotel” (1898) relates to something that happened to him in Lincoln (Nebraska). It is about a group, including a mentally disturbed person, that is cut off in a mountain resort hotel. Rejected by the main reviews at the time, Harper’s and Collier’s, Crane published it in a book entitled “The Monster and Other Stories”. King knew of him as a literature professor who had influenced stories including Hemmingway’s “The Killers”, which even borrowed The Swede’s name for his character.

Kubrick was also familiar with Crane’s story, because he had worked on the series “Omnibus” when James Agee adapted it for television in 1953. They were in fact, therefore, both inspired by Crane’s short story, where the protagonist’s fears focus on the idea that a murder took place in one of the hotel rooms, conjured up by the photo that the owner shows him of his dead daughter – coincidentally called Carrie, like King’s first novel, taken to the screen by Brian De Palma. If this were not enough, the ending takes place in a luxurious bar, where The Swede is having a friendly chat with a waiter. All very familiar.

DANGEROUS ENMITIES

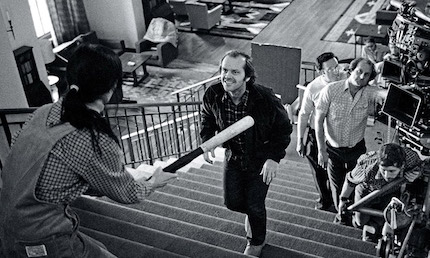

King wrote a cinematographic treatment on his own novel that was however rejected by Kubrick, who went to another literature professor, Diane Johnson, to write the film’s script. She had written a book about four characters in a house in Sacramento. Not best pleased, King did his own adaptation for television with his friend Mick Garris in 1997. It was a miniseries, not a film. Kubrick saw the problem of taking such a long book to the normal length of a feature film. It would have lasted for four or five hours, which would make it impractical for cinema distribution. As it was, 20 of the 140 minutes had to be cut for the European version.

Novel and film coincide in describing the main character, Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), as a troubled man. He is an ex-alcoholic, like King, who is trying to overcome his failure as a writer. He uses his time working as the winter caretaker of the Overlook hotel to write a new novel. He moves there with his wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and his son (Danny Lloyd), who he has abused in the past and who has developed an exceptional sensitivity, expressed through an imaginary friend on his index finger. The film plays down this fantastical element, suggesting that the ghosts are also in his mind. That is one of the criticisms made by King.

ROOM 237

The inspiration for the exterior and interior decoration comes from the Timberlake hotel in Colorado, which Kubrick turned into a giant set where he repeated take after take – with a record of 147 takes for one conversation –. His perfectionism extended to technical experimentation, whereby after having filmed by candlelight for the first time in “Barry Lyndon” (1975), he filmed almost the whole film with a new camera, the Steady-cam, which allowed shooting without rails. The delay that all this caused was compounded by a fire that broke out on the set in January 1979.

The film has been given an element of mystery by Kubrick’s obsession for numbers and geometry. In addition to the repeated use of the number 42, he changes the room number 217, for a number that does not exist, 237. It may have simply been at the request of the owner who might not have wanted a cursed room in his hotel. The fact is that the number has led to a whole series of speculations. It is the title of a documentary on various conspiracy theories thrown up by the film, upheld with great coherence in interviews and scenes to support the most ludicrous interpretations.

In the feature film directed by Rodney Ascher, “Room 237” (2012), we find out that the hotel that inspired King – the Stanley of Estes Park, Colorado –, was built on a tract of land linked to the genocide of the Navajo people. This would explain the continuous references to native Indians. Another theory puts Kubrick behind the supposed moon landing hoax, with the film allegedly providing clues. There’s another theory that links “The Shining” with the Holocaust, playing with numbers such as 42, the date of the Nazi’s “Final Solution”, as well as hidden words and symbols. Above all, the most frequent interpretation of the film hinges on the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, but in general the documentary suggests that any wacky theory is possible.

OUR PAST FOLLOWS US

What is clear both in the book and the film, is that our past follows us. Professor Simon Roy, a Canadian born in 1968, can’t write objectively about this story without identifying himself with the danger that Danny is in. Roy saw the film when he was 11 and when he heard the voice of cook Halloran – dubbed into French –, communicating telepathically with Danny, he felt that he was talking to him. He did not have the courage to watch it again until he was a teenager, when his mother tried to commit suicide. The first time was when he was 16, but she did not manage it until 2013, when she died of an overdose.

Roy’s mother was traumatised by her psychopathic grandfather, not unlike Jack Torrance. He murdered her grandmother by bludgeoning her to death with a hammer. Her aunt then disappeared in mysterious circumstances. She was her mother’s twin sister, just like the dead girls in the hotel. This Quebecois literature professor has seen the film 42 times, the number that is repeated over and over throughout the film. His book is something between an essay on cinema, a sociological treatise, a compilation of interesting facts, and a personal memoir. Published first in 2014, “Kubrick Red” is a chronicle of a voyage to the heart of darkness.

As some have said, this is not a horror story, but a story about horror. The film creates the possibility that the manifestations may not be real, but only ghosts in Jack’s delirious mind, unleashed by his alcoholism and madness, or in Danny’s childhood fantasies. Kubrick told Michel Ciment that he had liked the book because of the way that King entertained a certain ambiguity as to Jack Torrance’s perceptions. The monsters are not external but internal and, to use a Freudian figure, they conjure up the image of the father.

THE FATHER’S IMAGE

Every life is a universe. No father is alike, but in the end their imprints are alike. “We children come on scene late in our parents’ lives”, says Marcos Giralt Torrente – author of a book about his difficult relationship with a father that he barely knew –, but “it takes us even longer to realise it”. Parents, however close they may be, are always somewhat of a mystery. We never fully know them. They tell us stories of their life, but that’s all they are, stories, “a story by which they try to justify their lives depending on their failings and unfulfilled dreams”.

At the end of the day, what is a father to his son? Giralt Torrente asks. “Someone who we first try to imitate and from whom we then try to set ourselves apart”, to only discover later that we are everything that we hated in them. Giralt Torrente concludes that “at bottom, the conflict with the father figure, is the same as our conflict when facing reality: when childhood stories come crumbling down and we discover, horrified, that in life the good people don’t always come out on top”. Then, over the years, we end up accepting an imperfect world, trying to co-exist with our ghosts, even though we keep on trying to find an explanation for the inexplicable.

The doctrine of adoption is fundamental in understanding Christianity. It is when we know that we are God’s children and that He is our Father, that faith becomes a vital reality (John 1:12) that shapes our lives. The God of the Bible is a Father who has loved us from the very beginning, so that we can be his children (1 John 3:1). There is no other explanation for it other than the affection of his will (Ephesians 1:5). It is the difference between a slave and a son (Galatians 4:7). We are not his children through obedience, but by his adoption. He is our Father, whatever we may do. We may dishonour him and bring him shame, but we are his children. This realisation– that we have a Father who loves us – should transform our lives.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The monster within me