There is no balm in Atwood’s Gilead

“The Handmaid’s Tale” portrays the nightmare of a society governed by fanaticism and intolerance.

22 JUNE 2017 · 16:35 CET

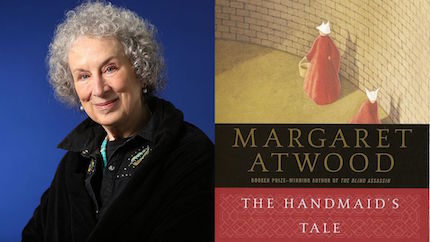

What would happen if the evangelicals came to power in the United States? The Canadian writer Margaret Atwood had only to look at the Puritan colonies of New England to imagine the reestablishment of the "Christian America" in Reagan´s time.

Her novel "The Handmaid’s Tale" (1985) has now become a series, made by the Hulu platform, portraying the nightmare of a society governed by fanaticism and intolerance.

I have made best use of a few post-op recovery days, to watch the series now made of this book that I first came across in the 80s. It was published in Spanish in 1986l - a time when religion was no longer considered a threat in Spain.

The background of the Moral Majority with which Atwood writes his story, is based on the Reconstructionism of a theonomy, which is at the base of the "dominionism" that has inspired American evangelical politics in recent years.

The bitter division that North American society has lived since the last elections can be traced back to the arrival of a Hollywood actor to the presidency of the United States, but especially with an increasing presence of the religious element which had been absent in previous administrations like Nixon´s presidency.

Many today forget that it was the Republicans who ushered in the freedoms that are now being resisted by conservative Christianity.

There are clear differences between Reagan and Trump. The actor had at least been governor of California. And his manners are not comparable with those of this former playboy who has made his fortune in casinos.

However, both of them wooed the evangelical community even promising an end to abortion and bringing the Bible back into the centre of the American way of life. No wonder they drew the vote of many conservative Christians who have made the defence of such issues a matter of faith.

THE MORAL MAJORITY

I came across this story in the early 80's. Although I had read Orwell's "1984", I did not know what dystopia was (the anti-utopia of an undesirable society) but I was passionate about Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World" (1932), a book that warned of the dangers of liberal society.

He imagined a dystopia based on a totalitarian regime like Nazi Germany or Soviet communism, but he had never thought of a conservative, Bible-based government such as we see in "The Handmaid´s Tale". Pious sounding phrases, coupled with that fertility cult, which condemned homosexuality and feminism, sounded too familiar to make me feel comfortable.

Atwood wrote his book whilst living in Berlin. She had studied Puritan America at Harvard and discovered that she had an ancestor accused of witchcraft in New England, namely Mary Webster, who survived the gallows.

That's why she developed her story in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The clothing worn by the unforgettable Peggy of "Mad Men" (Elizabeth Moss), is that of the Puritans who founded Harvard and we can see its library in the series serving as Gilead's secret service headquarters.

When the first president of Harvard, Henry Dunster, became a Baptist, he caused such a controversy that he was expelled from the colony.

The persecution of Baptists, Quakers, and Catholics that we see in the novel does not refer only to Puritan America. The parents of the Reconstructionist theonomy of the 1980s were conservative Presbyterians such as Rushdoony, Bahnsen, North, Chilton, or DeMar, who sought not only to implant the Mosaic Law, but also to persecute Baptists and heirs of the radical Reformation, with whom they disagreed theologically .

Few imagined then, that this sectarian fanaticism would become an evangelical movement as influential as "dominionism" - which takes its reference from Genesis 1:28, more than to the imposition it defends.

This connection with the Moral Majority advocated by Baptists such as Falwell or Robertson, coupled with Wagner's apostolic charismatic theology, leads onto a homeschooling movement that has already been the subject of many sociological studies in the United States.

"DOMESTIC FEMINISM"

One of the conclusions of the Reconstructionist social analysis is that feminism has ended the family order and upset the labour market. It idealized traditional society where women were not only homebased, but lacked legal rights, and whose biblical function was that of bringing children into the world.

The paradox is that those who extend this vision are women like Serena Joy who, in the book, appears as a former televangelist, married to a commander who is one of the architects of the Gilead Republic – a role interpreted by Joseph Fiennes, the actor who played "Luther" -. Her book on 'domestic feminism' serves to propagate these ideas, although later on it will not be read by women, who are not allowed to read at all.

The laws of Gilead will seem exaggerated to some. However, they are similar to those we met in Spain during the Franco regime. There is a legal limitation for women's freedom to employment as she needs the husband's permission to carry out any type of work or economic activity.

Women are snatched from their children for moral reasons. Not only is divorce and home abandonment prohibited, but adultery, contraception, prostitution and lesbianism are criminalized. The similarities with the evangelical agenda that has made abortion and homosexuality its "battle cry" are shocking...

What appears even more foreign to the Christian reader and viewer is the introduction of "the ceremony" in response to the infertility brought about by the deterioration of the environment - on which, it can be said, conservatives never seem to be very conservative.

Since "maids" are not only servants of the household, but surrogates of the wife, like Rachel using her servant Bilhá, they want to conceive a son for Jacob´s line through their maidservants (Genesis 30: 1-3).

This act is shown in a more sordid fashion than as an erotic piece. The series is accompanied, for the first time, with nothing less than with the soundtrack of the anthem "Onward Christian Soldiers". This confusion is difficult to swallow for any sincere Bible reader, who knows that this practice on the part of the patriarchs was more evidence of unbelief, than faith in the Promise.

The indoctrination method is carried out by "aunts" like Lydia in the Rachel and Leah Centre, a type of women who embody this system of brutal oppression by violence and cruel humiliation sprinkled with out of context biblical verses.

Aunt Lydia always repeats the blessedness of the meek, but as Offred says, she forgets the second part, "that they shall inherit the earth" (Matthew 5: 5). Domestic work is also left in the hands of "the Martha’s", women who have passed fertility and are referred to as “the friends of Jesus” like Mary and Lazarus (Luke 10: 38-42).

THE LAW'S INCAPACITY

A clear example of Atwood´s focus on the Reconstructionism of theonomy is his way of representing the death penalty. One of the vindications of this movement is its campaign for the reinstatement of the death penalty in all those cases established under Mosaic law instead of the contemporary penal system as the latter is not a biblical model and US prisons are full to the brim.

Another variation that they defend, given the current State application of the death penalty, is the victims' participation in the execution, as seen in "The Handmaid's Tale." This act of collective violence is, together with “the ceremony”, another of the story's more emblematic scenes.

Apart from a feminist focus or a liberal warning against the dangers of fundamentalism, one can also see "The Tale of the Maid" as a metaphor for the impossibility of the law to change people. As Paul shows in Romans 7:14-25, the law not only does not transform people. It simply cannot.

This is the difference between the Law and the Gospel. As Martin Luther said, confusing the two is the source of all the problems of the Christian religion. That is why evangelical legalism is a contradiction in terms. It seeks to obtain by the Law that which only Grace can achieve.

The title of Atwood's account actually reminds us of Galatians 4:21-31, where the freedom of Abraham's faith is contrasted with the bondage that Hagar represents. The apostolic warning is that we cannot return to the Mosaic bondage to achieve Christian freedom. It is only the Gospel that will set us free.

The Old Testament Law has a moral value for the Christian, but it has no judicial function for the world around us. If we continue to dream of imposing Christian ethics on society, what we will achieve is the hypocrisy lived in Gilead, where evil remains hidden in this "Christian nation," where there are still prostitutes like "the Jezebel." It is the double morality found within religious culture.

The ugliness of this world shown up under this cold light exposes the reality of religion without the Spirit. There is no shortage of pious expressions and biblical verses, but there is nothing of the power of the Word that makes all things new.

It is a law without mercy and a morality without grace. There is no balm in Gilead to heal any wound. That is only in Christ Jesus, because only the power of the Spirit of God can change our hearts. And he does this by his Grace, not by the force of the Law.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - There is no balm in Atwood’s Gilead