Schaeffer, a legacy of tears

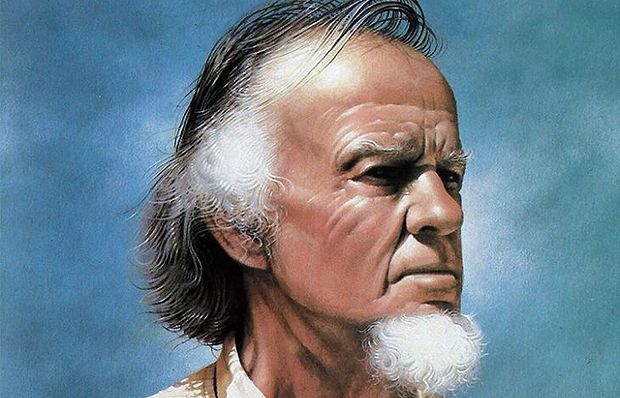

In search of authenticity (5). Schaeffer taught me how to mourn for the world, instead of judging it. He was a man of God who served as a prophet for his generation, which he understood so well.

18 OCTOBER 2017 · 11:40 CET

Evangelical Christianity finds sadness difficult to deal with. If you have found happiness in Christ, how can you be sad? It is like denying your faith, making you doubt your salvation.

Let´s not kid ourselves! Schaeffer was not the cheerful type. He wasn´t happy living in a lost world. Many of us can relate to that feeling, but I had never read how to hold on to both truths with the same passion that comes from the hope that faith gives us together with our despair for a lost world. Schaeffer taught me how to mourn for the world, instead of judging it.

I am going to wind up this series of articles dedicating some space to Schaeffer´s influence on my life. Anyone familiar with his work will note that he has been my role model in relating faith with the cultural world through its films, novels, songs, plays and art that speak of the death of a culture in a city that agonizes….

I remember when my mother, who died at an early age, was reading a book on the Madrid underground back in 1974 as we returned from school – I was around ten years old at the time – a book which had a black cover crossed over by a blue spiral and with the words “Death in the city” written on it.

A couple of years later I read these surprising expositions of Lamentations and Romans – which had been given as lectures at Wheaton College by Schaeffer in 1968 and published by Grau in Barcelona in 1973. I had never read anything like it. They were words bathed in tears.

WEEPING FOR THE CITY

God loved us when we were his enemies, even to the point of giving up his Son for us (Romans 5:10). That is why Jesus teaches us to love our enemies (Matthew 5: 38-48).

In order to love we must attempt to understand others although we can still love those we don´t understand. The singer-songwriter John Fischer, reflecting on Schaeffer's legacy in Christianity Today, discovers that his legacy of tears is something which evangelicals have not learned much from: "Too many of us are too busy beating up feminists, secular humanists, gay activists, and liberal politicians, to consider why they think the way they do." As they seem to be a threat to you, your children and the society around you, you cannot sympathize with them.

Our clear lack of empathy led Schaeffer to try to understand the culture of his time. As his own controversial son has said, "Dad was interested in secular culture not as a means to an end - to criticize or condemn it - but because it really did interest him."

In order to mourn for your own soul´s condition, as Fischer says, you have to "understand more fully its depravity and the depth with which the grace of God has reached us" as "you can´t cry for the world, if you have not cried before for your own condition".

HIS LAST BATTLES

Ranald Macaulay, his son-in-law and close associate– to whom I owe so much, not only for the knowledge he has given me about Schaeffer, but for his friendship and support in recent years - has written: "His social and passionate aversion to abortion during the latter years of his life has been sadly misunderstood , when it has been applied with less care and thought than he would have cared for, as he repeatedly warned, for example, of the danger of "shrouding Christianity with the American flag".

His son's accusation of being "the intellectual architect of the American religious right" not only places too much importance on Schaeffer, but forgets that it was precisely Schaeffer who pushed him into his political activism.

It is Schaeffer who puts him in touch with evangelical leaders "who knew practically nothing about him, such as Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, James Dobson, James Kennedy and the other televangelists, who would “use their power in ways that would have made my father vomit."

According to Franky himself, "Dad could scarcely have imagined how these would later assist to get into power a whole generation of false power-hungry evangelical public figures who immediately became corrupt such as Ralph Reed, who won his fortune in casinos."

I believe that when Schaeffer made his famous distinction between "alliance" and "co-belligerence," he was certainly not thinking of supporting a political agenda like that of the Moral Majority in the Reagan era.

On the contrary, he spoke of the civil disobedience preached by the Puritan Samuel Rutherford in "Lex Rex" (1644). When the conservative agenda becomes even more nationalistic in the Bush era after September 11 - though still only a shadow of what the Trump era has become - Franky recalls the phrase his father used to repeat about how "The next generation will follow anyone who promises peace and wealth, because if they ask you to choose between freedom and security, you will always choose security."

Franky may not be the most reliable source for understanding the Schaeffer's family relationships as he was the spoilt son who made life impossible for everyone, but as his father said over and over again, he was his greatest partner in the social and political battle of the last years.

The tendency to depression which he is said to have suffered seems to have worsened at the time of his illness, when he was about to die and was surrounded by "lunatics, psychopaths and extremists." He assures us that he said "if these idiots, who were by his side, win, America would have serious problems". His son said that the problem was that "I did not have time to change my life and find new friends."

PROPHET OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

He also talked about Bergman's and Fellini's films at Wheaton College, when students were still struggling to view Disney movies like "Bambi" or "The Love Bug." While Schaeffer was being passed a "joint " at a Jefferson Airplane concert, which he imperceptibly passed on to the hippy at his side – he bought several of the group´s albums the next day - Wheaton students and graduates continued to sign an agreement right up to 2003 whereby they could not drink, smoke or dance.

Those who consider him "the father of the American religious right" might like to read his book on the ecological crisis, published by the Baptist Publishing House in 1973, "Pollution and the Death of Man".

The contempt for environmental care, which began in the Reagan era and led to a deep scepticism about climate change during the Bush era, has now resulted in Trump's withdrawal from international agreements for reasons purportedly of "national political and economic interest". It is obvious that the current conservative agenda has very little to do with Schaeffer's thinking

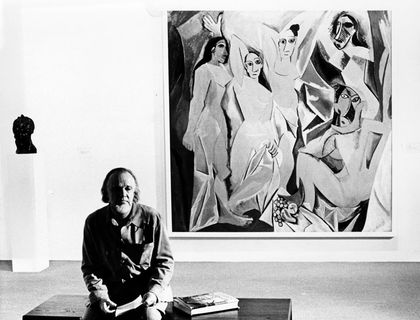

And if we mention the world of art, we would not only have to say that the evangelical world continues to be unable to grasp Rookmaaker´s idea, so often repeated by Schaeffer, that “art needs no justification”, but additionally the subculture which has developed within “contemporary Christian music” during the 1980s, has become a big business concern within the Latin context of " praise music ".

As Grau said, the Spanish speaking world does not understand Schaeffer's work. The Catalan theologian and publisher doubled the circulation of these books, precisely in order to reach Latin America, but they sold less than any other of his books. Schaeffer’s work still remains “a subject pending” - as Grau used to say - for the Spanish-speaking evangelical world

Grau, being a cessationist, never called any of his contemporaries a “prophet” except in Schaeffer´s case, because he saw in him a discernment and foresight that appeared to him to be of supernatural inspiration.

I, like my teacher, also think that the founder of L'Abri was a man of God who served as a prophet for his generation, and that he foresaw where the revolution of the 60s, which he understood so well, was going. I believe that it was not only in spite of his many defects and fragile humanity that God used him, but it was precisely because of his smallness and vulnerability that the Lord showed us that He is pleased to manifest His power in our weakness (2 Corinthians 12:9). To God be the glory, as Schaeffer would say.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Schaeffer, a legacy of tears