The Mosaic Law in light of ancient Near Eastern law codes

There are many skeptics today that argue that the laws contained in the Old Testament are written on the basis of earlier Sumerian and Babylonian law codes.

18 DECEMBER 2017 · 17:00 CET

There are many skeptics today that argue that the laws contained in the Old Testament are written on the basis of earlier Sumerian and Babylonian law codes.

The purpose of such theses is to question the Divine inspiration of Scripture and to demonstrate that the underlying principles in these texts are merely human, and dare I say, imitative in nature.

For someone who does not have a grasp on the subject, these theses can be quite persuasive at first sight. To give a popular example; it is possible to find the maxim "eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand" (Exodus 21:23, ESV) in the Code of Hammurabi which dates to a period at least 400 years prior: “If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out” (Article 196) or "If a man knock out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out." (Article 200).

What’s more, these similarities are not limited to the laws of Hammurabi only. For example, the Code of Ur-Nammu, which is at least 300 years older and thought to be by some the oldest Law code, states: “The man who committed the murder will be killed.” (Article 1) Compare this to the Mosaic Law which tells us that "Whoever strikes a man so that he dies shall be put to death.” (Ex. 21:12, ESV). Such similarities often lead to a very simplistic preliminary judgment that the Old Testament has perhaps copied these laws. Similarities may indeed exist, but similarity is not synonymous with causality. Moreover, similarities in wording and expression should be fairly normal for these laws, considering they all proceed from a common age and geography. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to say that similar laws point to humanity’s shared concern for justice more than to a mere causality.

To me, what is truly fascinating is the astonishing picture one is left with upon cross-examining the underlying principles of these law codes. I would go so far as to say that the laws of Moses show great differences with the spirit of Mesopotamian laws codes. In fact so much so, that I honestly believe that many do not realize the revolutionary character of the Mosaic laws for its day and age. In the following paragraphs I will be contrasting the differences between the Mesopotamian Codes and the Mosaic Law under four main headings, with special attention given to the Code of Ur-Nammu:

1) DIVINE SOURCE VS HUMAN SOURCE

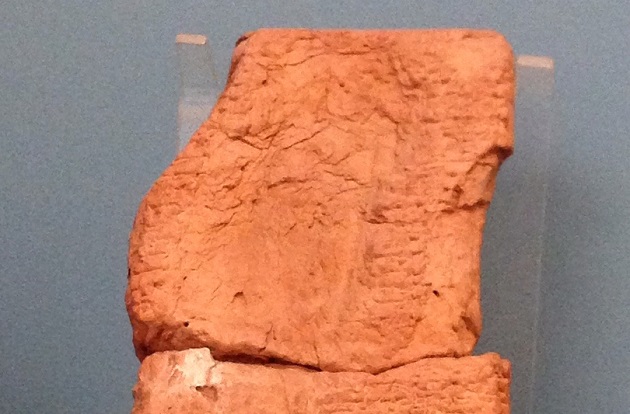

The Introduction to the Code of Ur-Nammu reads as follows: “After An and Enlil had turned over the Kingship of Ur to Nanna, at that time did Ur-Nammu, son born of Ninsun, for his beloved mother who bore him, in accordance with his principles of equity and truth... Then did Ur-Nammu the mighty warrior, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad, by the might of Nanna, lord of the city, and in accordance with the true word of Utu, establish equity in the land; he banished malediction, violence and strife, and set the monthly Temple expenses at 90 gur of barley, 30 sheep, and 30 sila of butter.”

From this statement, it is understood that this law code emerged at the initiative of King Ur-Nammu. The reason for the writing of this law is not necessarily a particular god but the king's own will. Although the king emphasizes that some deities may have provided spiritual support and direction to him, this is quite different from the claim of divine origin made in the Mosaic Law. Contrast this with the introduction and direct voice of God found in Exodus 20:1-2, “And God spoke all these words, saying “I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” (ESV)

It is evident that Ur-Nammu and other similar ancient laws were recorded at the initiative of the kings themselves. Whereas the Old Testament text clearly states that the laws came directly from God. In this context, the Old Testament is making a revolutionary claim, a claim of divine legal authority that had not been heard of until that day.

2) THE CONCEPT OF EQUALITY AND THE REASONS FOR PUNISHMENT

In the Mesopotamian understanding of justice, the aim of the law is to bring order to society. But it is quite difficult to say that this method is equitable to today's understanding of equality under the law. For example, in the case of Hammurabi’s Code, those who have a higher social class undergo lighter forms of punishment compared to those who commit the same crime but belong to a lower class. Compare the three levels of class-based-punishment found in articles 202, 203, and 204 of the Code of Hammurabi:

- Article 202: If any one strike the body of a man higher in rank than he, he shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public.

- Article 203: If a free-born man strike the body of another free-born man or equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina.

- Article 204: If a freed man strike the body of another freed man, he shall pay ten shekels in money.

The Mosaic law is quite different in this regard, because punishment depends on the nature of the crime rather than the social class. One of the most important reasons for this is that the law of Moses is not based un class sensibilities. Rather, it is based on the sanctity of each individual life created in “the image of God.” Its concept of law is anchored in the idea of “God’s holiness" rather than the protection of the socially elite: "You shall be holy to me, for I the LORD am holy and have separated you from the peoples, that you should be mine.” (Leviticus 20:26, ESV)

3) A DIFFERENCE IN FOCUS WHEN IT COMES TO CAPITAL PUNISHMENT AND MONETARY COMPENSATION

Perhaps one of the most striking differences between the Old Mesopotamian codes and the Mosaic Law is the nature of punishments for crimes committed against human dignity. In the most general sense (though there are some exceptions), in the laws of Ancient Mesopotamia crimes committed against human dignity are punished with fines, while crimes against property are punished with death. In the Mosaic Law we observe an opposite approach. For while sins against human dignity are punishable by death, property crimes are converted into fines. The following examples make this difference quite obvious:

- Ur-Nammu, Article 2: “If a man commits a robbery, he will be killed.”

- Mosaic Code, Exodus 22:1: “If a man steals an ox or a sheep, and kills it or sells it, he shall repay five oxen for an ox, and four sheep for a sheep.” (ESV)

- Ur-Nammu, Article 3: “If a man commits a kidnapping, he is to be imprisoned and pay 15 shekels of silver.”

- Mosaic Code, Exodus 21:16: “Whoever steals a man and sells him, and anyone found in possession of him, shall be put to death.” (ESV)

- Ur-Nammu, Article 28: “If a man appeared as a witness, and was shown to be a perjurer, he must pay fifteen shekels of silver.”

- Mosaic Code: Deuteronomy 19:18-19: “The judges shall inquire diligently, and if the witness is a false witness and has accused his brother falsely, then you shall do to him as he had meant to do to his brother. So you shall purge the evil from your midst.” (ESV)

4) GREAT DIFFERENCES IN PUNISHMENTS GIVEN TO WOMEN

The position of women in ancient law codes is of course far from our 21st century sensibilities. However, when we compare these laws with the Mosaic code, we do find that the Mosaic code draws a more just and equitable line. For example, in the Ur-Nammu code, a woman committing adultery is subjected to capital punishment while the man is set free. In contrast, in the Mosaic Law both men and women convicted of adultery are subject to capital punishment. In the Ur-Nammu code the penalty given to a man who abuses a virgin is 5 shekels of silver. In the Mosaic Code the punishment is 10 times harsher, 50 shekels. Additionally, it was expected that the abusing man marry the virgin and lose all his rights for divorce. This is, in case the virgin’s father were to accept the arrangement. If the virgin’s father refused, she could continue to live under her father’s protection. The culprit was expected to pay the dowry price regardless. This last measure may seem rather strange and cruel to our modern ears, but what it meant to achieve was to shame the perpetrator and insure the material support of the woman for the rest of her lifetime. Here we can take a glance at such laws:

- Ur-Nammu, Article 7: “If the wife of a man followed after another man and he slept with her, they shall slay that woman, but that male shall be set free.

- Mosaic Code, Leviticus 20:10: “If a man commits adultery with the wife of his neighbor, both the adulterer and the adulteress shall surely be put to death.” (ESV)

- Ur-Nammu, Article 8: “If a man proceeded by force, and deflowered the virgin female slave of another man, that man must pay five shekels of silver.”

- Mosaic Code, Deuteronomy 22:28-29: “If a man meets a virgin who is not betrothed, and seizes her and lies with her, and they are found, then the man who lay with her shall give to the father of the young woman fifty shekels of silver, and she shall be his wife, because he has violated her. He may not divorce her all his days.” (ESV)

- Mosaic Code, Exodus 22:16-17: “If a man seduces a virgin who is not betrothed and lies with her, he shall give the bride-price for her and make her his wife. If her father utterly refuses to give her to him, he shall pay money equal to the bride-price for virgins.” (ESV)

In conclusion, we observe many differences between the Mosaic law and Mesopotamian codes. While the Mosaic code emphasizes that laws come directly from the Deity, the texts of other civilizations emphasize that the laws are based on the initiative of a ruler. While the Mosaic code is based on the holiness of God and the sanctity and of human life, the laws of Mesopotamia are based on preserving or protecting a particular social class or elite. While the Mosaic code applies the death penalty to crimes against human dignity, Mesopotamian laws implement this punishment to crimes mostly against property. While the laws of Mesopotamia draw a highly prejudiced line against women, the Mosaic code proves to be more equidistant. In short, the Mosaic code is quite revolutionary for the times! So, where did this understanding of law come from? I’m fully aware that this study in of itself doesn’t prove beyond a doubt the Revelation of Scripture. However, it is plain to see that claims that the Mosaic code is somehow an imitation or inspired from Mesopotamian texts are rather simplistic and naive.

If there is something definite, it is that the Mosaic code offers an innovative thought approach unseen until its day. Definitely not seen in Mesopotamian civilizations for sure. This extraordinary way of thinking reflects, in my humble opinion, a law code written as a result of divine inspiration an not imitation.

Marc Madrigal is a a board member of Istanbul Protestant Church Foundation in Turkey.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- “Code of Ur-Nammu.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

- “The Code of Hammurabi,” Translated by L.W. King. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/

- Joshua J. Mark. “Ur-Nammu,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. http://www.ancient.eu/Ur-

- Gabriele Bartz, Eberhard König, (Arts and Architecture), Könemann, Köln, (2005).

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Archaeological Perspectives - The Mosaic Law in light of ancient Near Eastern law codes