Faith in crisis

Books, series and films have left us with striking testimonies of those who, while representing Christianity, wonder where their faith is. An article about three of the most acclaimed stories of 2018.

28 MAY 2019 · 09:42 CET

Last year brought us many stories of pastors in crisis. Of the twenty stories brought to us by Christianity Today, the majority were about well-known preachers who had had to leave their ministry for different reasons.

Books, series and films have left us with striking testimonies of those who, while representing Christianity, wonder where their faith is. This article refers to three of the most acclaimed stories of 2018.

Many believe that the first detective story was written by Edgar Allan Poe with his The Murders in the Rue Morgue, but an earlier novel was written by a Danish Lutheran pastor telling the story of a preacher suspected of murder, being investigated by another protestant minister.

The Vicar of Veilbye (1829) was written by Steen Steensen Blicher (1782–1848). It has been translated into other languages. Although it is not easy to find, I was very impressed by it when I finally had the chance to read it during my recent hospital stay.

Another book of his was Diary of a Parish Clerk. Besides the specificities of Danish Lutheranism, this is a story about a pastor in crisis, written by another pastor who also encountered serious difficulties.

The author had economic and marital problems, while his fictional character is embroiled in a criminal case putting his life at risk.

The novel is based on a real story and was quickly translated into English, but instead of giving it the publicity that it deserved, Mark Twain used the story for one of his own novels without mentioning the author.

Steensen Blicher wrote another book about the Spanish Inquisition, Donna Leonora (1825), which may refer to Leonor de Vibero – the mother of a certain Dr Cazalla, whose house was a meeting place for Protestants in the Spanish city of Valladolid until they were burnt in the autos de fe that extinguished the Reformation in Spain – but it seems that the novel was never translated.

Reading The Vicar of Veilbye makes you want to get to know the author better. He writes with a great economy of language at a time when style tended to be florid and pretentious.

It’s a modern novel and an intelligent narration of the story through the diary entries of the judge and the vicar. The proceedings are described using legal terms and without taking sides.

The reader knows as much as the judge and the narration doesn’t get ahead of itself or play tricks. We follow the judge’s notes and that of his successor, leading to a surprising ending that sheds a very different light on the problem faced by the pastor.

The question is whether the minister, in a fit of rage, killed the servant working in the vicarage, the brother of a farmer who calls on the judge to bring all the weight of the law down on the accused pastor.

We see the vicar tormented by guilt and full of doubts, at times making us think that he is guilty and at others that he is innocent.

As I read about his distress, while I myself was in some pain after my operation, I started thinking about a text by Francis Schaeffer’s wife, Edith (1914–2013), who talks about the fits of rage that the Christian apologist would get into, once when she was in the middle of labour pains.

The shameful humanity of the founder of L’Abri, which has had such a strong influence of me, rang a chord. I have also felt that rage and the desire to hurt even those I most love. We are our worst enemies, capable of destroying ourselves and the people we cherish the most. As the apostle Paul in Romans 7, we may well ask ourselves who will free us from this internal contradiction. The answer is the Gospel, which is just God’s Spirit through Christ, and it starded in the next chapter.

SOMETHING TO BELIEVE IN

The Danish series Borgen has not only been a phenomenon in the history of television – shown in more than 80 countries –, but it was also the subject of political debate – even in countries far removed from a Scandinavian reality, such as Spain –, since it showed the complexity of a coalition government.

While Adam Prize’s show goes into the intricacies of the constant power play with opposition parties and the media, the Prime Minister’s character appears relatively flat, compared with the main character in his new series, a Protestant pastor who hasn’t yet grasped who he really is.

The original title Herrens Veje (The Ways of God), making reference to William Cowper’s poem God moves in mysterious ways, has been rendered in English as Ride upon the storm, which is a quote from the same poem.

Cowper was the co-author of many hymns with John Newton, the vicar at the Anglican church of Olney who has gone down in history for the Amazing Grace that transformed him from a slave trader into a preacher who turned the politician William Wilberforce into a fervent abolitionist. In the series’ opening theme we hear modern worship song verses in English.

The series, presents a Lutheran pastor in Denmark, where not only the Prime Minister is a woman, but where there are female bishops, like the one that the main character meets at the episcopal election held at the start of the series.

If we find the bishop to be thoroughly unlikeable, it isn’t a question of him being a man and she a woman, but because questions of gender no longer determine the kindness or evil in characters.

We are in a post-feminist society, where these are topics of daily debate.

Not only is the position of women very different but the Lutheran church is far removed from other evangelical denominations.

Denmark is a Protestant country. It has an Evangelical Pietist section which is very conservative, but which is as firmly Lutheran as the Church of Denmark of which it is part. The main character is a member of this official church.

He comes from a family of pastors going back some 250 years, and one of his sons is also a pastor. It is a historical church that distinguishes itself more by outward signs, such as clothing and liturgy, than by doctrine and way of life, and is generally not very evangelical.

The pastor’s crisis, brought to us so powerfully by Lars Mikkelsen, shows us, in the words of Price, “a Biblical scene”. The pastor is a father with two sons, who take very different paths, not necessarily in line with their father’s expectations.

He shows his patriarchal favour towards the tormented August, while he makes no attempt to hide his disappointment in Christian, whose story is similar to Borge’s story of the pastor’s son who became a Buddhist.

The personality of the minister, Johannes, is larger than life, full of charisma, but also tortured.

Although it is a series about faith, many believers will be shocked by the crude way in which the pastor’s misery is portrayed. Many will consider that his excesses with alcohol and sex are exaggerated, but I can assure you that they are not far from reality.

His wife, Elizabeth, is an interesting character. He leans on her, and she defends him and supports him come hell or high water. They have something of an open relationship but their continuous infidelities do not seen to be able to break their bond.

It’s as if the characters were seeking in human love, that which they were unable to find in providence, only highlighting their loneliness...

THE TORTURED REVEREND

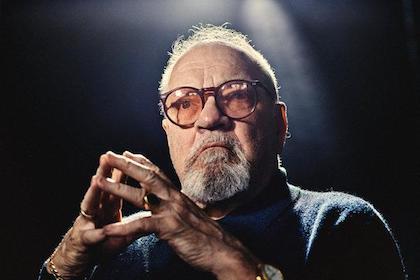

That is also the perspective of the transcendental tradition in cinema, which interested Paul Schrader early on when he quit his theology course at Calvin College, Grand Rapids (Michigan), to go to California.

Despite having received a Christian upbringing and not being allowed to go to the cinema or watch television, he became a cinema expert. He first started writing as a protégé of the film critic Pauline Kael, before starting to write scripts with his brother Leonard, who had been a missionary in Japan.

Together they wrote Yakuza for Pollack. In some ways, all his work as a film director revolves around the obsession that surfaced in Taxi Driver (1976), which he wrote for Scorsese, which is nothing but the reflection of his own life, caught between anger and grace, the spirit and the flesh.

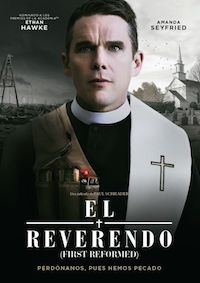

The struggles of Schrader’s characters seem so familiar to me that I wasn’t at all surprised when he announced that he was making a film – First Reformed – about a pastor in crisis in the First Reformed Church of a small town in the State of New York.

This is where he himself has started to go to a Presbyterian church, whose pastor was in fact one of the film’s advisers and who presented it to the congregation, before presenting it evangelical seminars like Fuller.

Like the pastor’s son in the Danish series, Pastor Toller was a military chaplain who loses his wife when their son dies in Iraq.

The film coincided with a new revised publication of Schrader’s thesis on the transcendental style of the films of Ozu, Bresson and Dreyer.

It is therefore no coincidence that the films starts off like the Diary of a Country Priest (1951) by Bresson, although it continues in the style of Bergman’s Winter light/The Communicants (1962).

The difference is that Schrader is the author of Taxi Driver. For this reason Toller soon turns into a copy of Travis – the character played by Robert DeNiro in Scorsese’s film.

The ecological question therefore is no more than an update of the problem of urban violence in New York in the 1970s, introducing Schrader’s subjects of interest in Toller’s tormented faith, drowned in alcohol, an obsession with weapons and eroticism.

Schrader’s films tend to be rejected by a Christian audience, not because of their characteristic slow pace – something that most people that are not used to this type of cinema observe – but because of the sordid world that films like Hardcore (1979) present. It is a harsh and disturbing film, like life itself.

In a way, the film – as Brett McCraken observes – is the story of two churches. This First Reformed church is part of the tradition brought in by Dutch emigration during the colonial period.

It has a lot of history but a depressing present. Less than a dozen people sit on the benches to hear Toller’s sermons. The Church of Abundant Life, on the other hand, is a mega church planted by the First Reformed church and which actually maintains its mother church.

Its huge installations presents a form of prosperity gospel. It has its own a coffee shop, a youth ministry and a pastor covered in tattoos. There is no doubt which church is attracting more people.

One is an attractive church that does not address uncomfortable subjects, bringing down discipleship costs and shielding a congregation maintained by conservative businessmen from the justice of the gospel.

The other church has a melancholic feel to it and raises controversial subjects, swapping worship for political activism.

The Abundant Life and the First Reformed Churches represent two trends in the Church today, the evangelical nominalism of cheap grace and the liberal theology of historical denominations. They are both fighting for the heart of the evangelical movement.

As McCracken says, ultimately the struggle between the churches reflects what the pastor is going through, or, better still, the conflict of Christian life: “the cross and the resurrection, spare simplicity and gratuitous abundance, fasting and feasting, suffering and joy, pessimism because of sin and optimism because of sanctification, despair and hope”.

The journey through the dark soul of Toller communicates the tension found in his diary. He struggles between hope and despair.

He realizes, as Merton says, that “Despair is a development of pride so great that it chooses someone’s certitude rather than admit that God is more creative than we are”.

At bottom it is “the absolute extreme of self-love. It is reached when a man deliberately turns his back on all help from anyone else in order to taste the rotten luxury of knowing himself to be lost”.

The spectator is faced with an incredible event in the context of a banal reality that can only be accepted by faith. This is how First Reformed shows us the disparity in that “spiritual schizophrenia”, reflected by the two churches: two extreme expressions of faith that point to the paradoxes of Christian life: truth and love, mercy and judgement, grace and discipline. It isn’t easy, but as in Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959), at the end we will discover that “all is grace”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Faith in crisis