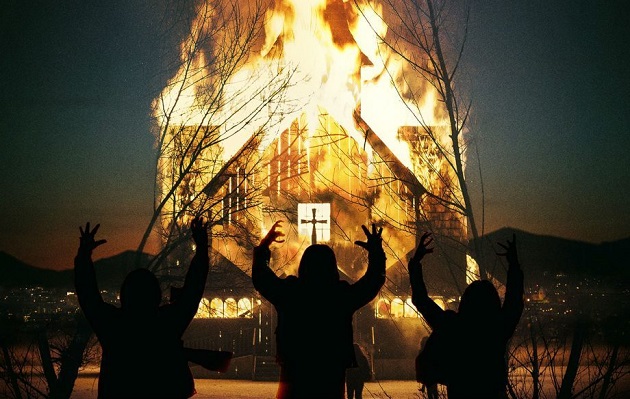

‘Lords of Chaos’ film tells origins of Norwegian black metal

What is the connection between the burning of Norwegian churches in the 90s and the appearance of the Scandinavian rock genre?

18 JUNE 2019 · 10:18 CET

This story was originally published by Religion Unplugged. It was re-published with permission of the author.

With the cross as the symbol in its flag, it can seem strange that black metal has become a well-known cultural export from Norway. Or maybe not.

This year, Norwegian black metal has been in the spotlight because of the Swedish-British film Lords of Chaos. The reviews have been mixed in Norway.

“A clueless poser film which has nothing essential to say about how the completely Norwegian black metal genre was created, what this music represented or what motivated the key persons in the community,” a critic in the center-left daily Dagsavisen wrote.

Black metal is often chronicled by music historians as emerging from Oslo in the 80s early 90s. The genre became infamous with the ’93 arrests and ’94 convictions of its leaders in church burnings, murder, assault and possession of explosives.

The “first wave” of black metal music is characterized by heavy chords that use all the guitar’s strings instead of two or three, sometimes, Satanic lyrics, and visually dark themes like using body paint resembling a corpse.

The film attempts to retell the troubled history of the genre’s earliest band, Mayhem, through its guitarist, Euronymous (who named himself after a Greek flesh-eating demon), just 14 years old at the band’s formation in 1984. In 1991, he found the lead singer Dead lying still on the floor with slit wrists and a shotgun blast to the head. It was Dead’s bloody suicide in part that brought fame to the band. A photo taken by Euronymous of Dead’s body was later used as album cover art.

No matter how the film, based on a book, is received, the music has its fans in surprising places.

“Wow! Norway. So, black metal.” That was the spontaneous reaction from the young Native American Elijah Martinez to a journalist from the Norwegian newspaper Aftenbladet in a recent story. The journalist was in the desert on the US-Mexican border to write about President Donald Trump’s planned wall but got questions in return. “Are you still burning churches?” Martinez asked.

Varg Vikernes, known as The Count, became one of the most well-known figures from the Norwegian black metal scene for his convictions for burning three churches in 1992 (though several more burned too). He changed his name from Kristian Vikernes.

For the most symbolic church burning, of the picturesque Fantoft stave church in Bergen, Vikernes was acquitted by the lay jury, even though the judges found him guilty. The fire started on June 6 at six o´clock in the morning, i.e. 666, the number of the Beast in the Book of Revelation. [I remember hearing the news on the radio. I was almost 13 years old, and the event stoked fears in me. What terrible things were going on in Christian Norway?]

“I remember the whole media-driven scare about black metal when I was a kid, but the music was far beyond anything I listened to then, and I am pretty sure my mum would not let me listen to it anyway,” Anders Martinsen said in an email interview. He is a theologian and associate professor at Oslo Metropolitan University.

“Most people know more about the history of the early scene of black metal with all the violence and torching of churches, which is a sham,” he said. “The genre of black metal music should not be conflated with the extreme parts of its early history.”

Martinsen underscores that rock music from the beginning has been accused of devil worship. Even the Beatles were labelled as anti-Christs. But in the late 60s, bands like Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath took the music in a heavier direction, and integrated parts of their fascination with the occult.

“At the same time, in the late 60s early 70s, Satanism emerged in US, which took the classic occultism, Spiritism, esoteric magic and the like and gave it a certain Satanic flavor, maybe more for the effect than actual belief. This created a Satanic scare in the States and had tremendous shock value. Bands like Alice Cooper and Kiss had already showed that it was possible to generate fame introducing theatrical effects on the stage, but as they became more mainstream the ‘danger’ disappeared,” Martinsen explained.

An evolving heavy metal style, that did little to court to mainstream audiences, and horror movies, that struggled to get passed the censorship, were among the sources of inspiration for the emerging black metal bands.

“I believe black metal bands understood the value of being perceived as underground and a bit dangerous,” Martinsen said. He thinks this attracted listeners who wanted to be part of a provocative movement.

Question. How important was religion and the opposition to Christianity for these artists?

As late as in 2000, 86.5 percent of the population were members in the Church of Norway, according to Statistics Norway. Many of the rest were members of other Christian denominations.

“The church and Christianity was a perfect target for anyone who wanted to provoke, upset the establishment, and get attention. Christianity was seen as repressive and backwards. Its values were diametrically opposite of the black metal movement,” Martinsen said.

The opposition to Christianity has become less important for Norwegian black metal musicians as they have grown older, become fathers and so on, according to Fredrik Horn Akselsen. He is one of the makers of the film Blackhearts, which portrays three fans of Norwegian black metal from Greece, Colombia and Iran. For these fans, the faith perspective was immensely important, as part of a rebellion against the dominant religion in their own countries.

Q. A lot of people will perceive Satanism as dark, threatening and destructive. How do the persons you have met, view this?

Akselsen: “In different ways. In Colombia there was real Satan worship, and they viewed this as dark and destructive, but embraced it. In several cases persons used Satanism to put themselves outside society and appear as outcasts. The Iranian was not a Satanist but was non-religious and cultivated music in Persian mythology and Iranian history.”

The fascination for extreme could have several consequences. Some of the Greek artists had joined the fascist party Golden Dawn, and both the Colombian and Greek expressed an urge to break down the Christian world.

Q. What do they think about church burnings, homicides and so on, which has taken place in the black metal community?

Akselsen: The Norwegians I spoke to, found this fairly crazy. Some of the cynics said it helped to sell records and put the genre on the map in the early 90s but that it was a stupid and bad idea today. The foreigners answered not much to this, but it was clear that killings and church burnings in Norway made the genre more legitimate and came across as “real”.

Akselsen added that “true Norwegian black metal” is an expression for the genre as more serious, scary and dangerous than other kinds of metal, music and culture.

Q. What have been core values and convictions for the Black Metal community?

Martinsen: I am not sure it is a scene that would be happy to rally under a shared set of values. When that said, the ethos seems to cluster around ideals such individualism, freedom, opposition to the establishment, never compromise. In effect, the same values like a lot of other bands from different genres harbored, but these bands took it a bit further with a style that was meant only for those who liked it, and with no care for those who did not.

Tore Hjalmar Sævik is a Norwegian journalist.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Features - ‘Lords of Chaos’ film tells origins of Norwegian black metal