Asterix holds out

The ending of Asterix books reminds us the Story par excellence, the Bible - banquets point to our yearning for a happy ending.

12 NOVEMBER 2019 · 09:10 CET

Asterix is turning 60. A new book of this popular French comics series has been recently published worldwide, “Asterix and the Chieftain’s daughter”.

While the United States has its superheroes and Japan its manga, Europeans have spent half a century being fascinated by the Bande Desinée (BD) of this Franco-Belgian comic.

“One small village of indomitable Gauls still holds out against the invaders…”. That is how every Asterix books begin. The Gauls’ rebellion against the Empire is not easy for a North-American audience to understand.

There, readers identify themselves more with Rome than with the small village. The Japanese, for their part, do not understand Asterix’ individualism and lack of discipline. Not everyone gets Asterix.

The French Third Republic reinvented their “Gallic ancestors” to promote left-wing laicité against the legistimist catholic right-wing. Asterix, however, re-writes History with the chaos and insubordination of these indomitable Gauls, who make a mockery of the studied strategies of the Roman army.

Vercingetorix does not lay his weapons down at Caesar’s feet but bang on top of them, so that the Roman leader has to hobble off to his other conquests. The soldiers resign themselves to “Gallic peace” with a negligence that is quite alien to Roman order.

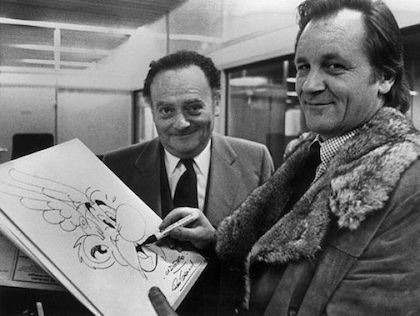

When the authors of Asterix holed themselves up in the Bobigny apartment owned by Uderzo (1927) – a French cartoonist originally from Italy – in the summer of 1959 to create a series for the new magazine Pilote, they went over the main periods of France’s history.

“The village was born before the characters”, recalls René Goscinny (1926–1977) – a Ukranian–Polish Jew who grew up in Buenos Aires. “The village where a few half-mad Gauls held out against their enemies, the Romans”.

A LITTLE MAN

His antihero is “a little man”, says Goscinny – weak and puny, a “little fellow as perceptible as a punctuation mark”. Nothing like the blond, tall and brawny Gauls that appeared in the history books.

The author of Lucky Luke, Iznogoud and Le Petit Nicolás, did not want to have a side-kick, but Uderzo convinced him by drawing an Obelix who is not Herculean, but fat, even though he doesn’t think he is – “just well covered”. He got his strength when he fell into a cauldron of magic potion when he was a baby.

Obelix’ profession is not one known to the historians of the Gallic era: a quarry worker and menhir carrier – a voluntary anachronism which should not be attributed to any ignorance on Goscinny’s part.

Although he had documented himself thoroughly, he wanted to make some stuff up, to the irritation of many of the academics who today study his stories – in France there are university professors who specialize in Asterix studies!

Similarly, Goscinny borrowed the Merovingian practice of carrying the chieftain on a shield, so that Vircingetorix can constantly fall off it. He also brings in the Goths, whose Prussian militarism is a clearly premonitory of Nazi totalitarianism.

The script even says that they march like the armies of the Third Reich. The swastika is replaced on their standard by the black eagle, which also appears in the insult bubbles.

And even though they carve up their opponents in the circus arena they come up with the idea of a “pressure cooker” which “boils a man in two minutes and whistles when it’s ready!”.

AN ARGENTINIAN JEW

Although Goscinny is considered to be quintessentially French, his parents were Ukrainian-Polish Jews who were not nationalized as French until a few months before René was born.

Exile in Argentina spared the family from the Nazi occupation although three of his uncles died in Auschwitz. When he was only two years old, his parents took him to Buenos Aires, where he studied at a French school.

The teachers and children in the stories of Le Petit Nicolás are therefore not so much French as Argentinian. The characters of these books – which are not comic books but children’s literature, with illustrations by Sempé – depict the teachers and students at the school on Pampa street.

When his father – a chemical engineer from Warsaw – died of a brain haemorrhage in 1943, René had to start work at the age of 17. Two years later, he and his mother moved to New York.

The Goscinnys arrived at Ellis island along with all the other immigrants fleeing the shadow of the Holocaust and drawn by the “American Dream”. His uncle lived in Manhattan, where he worked as a translator.

Goscinny left the United States to avoid doing the military service and returned to France, where he began his drawings. He then returned to New York in 1947. He would ironically say that he went back to the United States to work with Walt Disney, but that Walt Disney knew nothing.

He was alone and depressed when he met Harvey Kurtzman, the Jewish cartoonist who would go on to found the satirical magazine “MAD”. He worked in his studio until he was introduced to the Belgian Morris. Together they created Lucky Luke, a parody western.

Goscinny understood that his strong point was writing stories, not drawing them. The job of a comic strip writer was not widely recognized at the time. In general, they were not even given a mention in the publications and their pay was not included in the editorial accounts.

It was the cartoonist who paid the script-writer. Morris moved from Brussels to Paris, to pay him, and there Goscinny started working with Charlier, the author of “Blueberry”, and did his first collaborations with Uderzo with the Indian “Umpa-pa” and the pirate “Jehan Pistolet”.

THE SKY IS FALLING ON OUR HEADS

Although the magazine Pilote was born in 1959, the first Asterix book was not published until 1961, achieving some success by 1964, with “Asterix the Gladiator”; becoming something exceptional by 1967, with “Asterix in Britain”; and establishing itself as a phenomenon in 1967, with “Asterix and the Normans”.

It is therefore a product of the 1960s. That is the decade in which its most popular titles were published. Its fame extended into the beginning of the 1970s, later entering a period of decline prior to the death of Goscinny in 1977.

He died during a routine medical check-up in a clinic in Paris, following a trip to Jerusalem. He had a heart attack in the cardiologist’s surgery.

Uderzo’s work since then has been a parody of current affairs, which has become increasingly clumsy. Uderzo is a great cartoonist, but a bad scriptwriter. The best decision that he took since the death of Goscinny, was to leave the series.

“The sky is falling on our heads! (2005) was already a mixture of references to Disney, manga and superheroes, even in the cartoons. The new authors, Ferri and Conrad, have returned to Goscinny’s original style, but have continued the comments on the present.

THE SHORTEST PATH

In 1919, Count Keyserling said that, “the shortest path to finding yourself circles the world”. The question of identity is essential in order to understand the world of Asterix, but none of his stories can be understood without a journey.

When Uderzo asked Goscinny where the village was, he answered “Somewhere close to the sea, that will make the trips easier”. He had loved the sea ever since he crossed the Atlantic as a child to go to live in Buenos Aires and from there to Ellis island to live in New York.

Goscinny loved cruises and it was on such a cruise that he met his wife Gilberte in 1964. He even published a book about his trips.

Asterix and Obelix’s trips enable them to explore national stereotypes. Their adventures sometimes take them to nearby places, but they general cross some kind of border to find other friendly or unfriendly villages.

Asterix and Obelix go to Egypt, Africa, Greece, America, India, the Middle East, and even to Atlantis. The interesting thing is that they never lose their point of reference, the village in Armorica that is still holding out against the invader.

Recurrent themes can be found throughout the books, with pirates sinking ships, Obelix being deprived of magic potion, meeting Roman patrols and searching for boars.

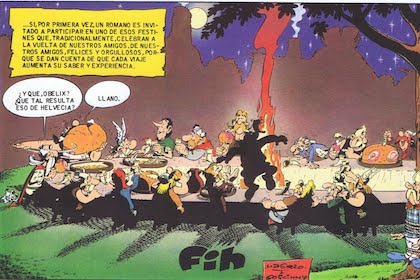

What we know is that the story will end with a banquet. Around the table, the inhabitants of the village will celebrate the end of the adventure. In the first books it only occupies one strip, where the banquet can be seen from afar, through the half-open door of a hut or even with the bard still playing the fiddle and shouting his head off.

The books then started to give the banquet half a page, showing a round table surrounded by the village men, with the exception of the bard, who is left outside, bound and gagged.

While the journey takes us back to the epic model of the myths of antiquity, which accompany the hero in his odyssey, the ending reminds us the Story par excellence, the Bible. Jewish festivals included banquets, at which the “widow, the orphan and the foreigner are welcome” (Deuteronomy 16:11).

The sacrifices provided for by law included banquets (Exodus 34:15). The celebration was not only a show of hospitality, but also of generosity, given that part of the food was sent to the poor (Nehemiah 8:10).

THE FINAL BANQUET

The Gospel is full of celebrations. Jesus begins his ministry at a wedding, but he not only enjoys celebrations in the company of his friends, but also of people of doubtful morals, contrary to those of many of his followers.

Jewish celebrations generally involved a dinner at the end of the day. The invitation was sent twice (Matthew 22:3; Luke 14:7), until the owner of the house closed the doors to the celebration with his own hands (Luke 13:25; Matthew 25:10).

The Jews had the hope of participating in an eternal banquet with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Jesus talks about this banquet over and over again. He gives a new meaning to the celebration of Passover and institutes a supper in remembrance of himself. We share bread and wine “until he returns”.

That is when the real celebration will begin (Apocalypses 19:7). For that celebration, he now sends out invitations through his servants, given that when that day comes, those who do not come prepared will be left outside. Once the door is closed, it will be no use knocking. It will be too late. Only the darkness outside will remain.

I remember watching the first Asterix film in a cinema in the Spanish city of Logroño. I think that it is the only time that I have accompanied my uncle and cousins on such an outing. I was very young, but I knew the stories from the cartoons that we had as children.

At that time of black and white TV, I was fascinated by the colours, but I only remember one scene: the final banquet. Bathed in the soft light reflected from the protective moon, it presented a picture of a loving family and the utopia of a happy community.

Although, as Panoramix explains in “The Mansions of the Gods” – the only book I was ever given for one birthday, after having read “Asterix at the Olympic Games” to bits–, it is not always possible to make time stand still, the banquets in the Asterix stories show humanity’s yearning for a happy ending.

The Gospel invites us to such a celebration. It is true that the Church today isn’t a very festive place and seems to have little resemblance with Jesus, the friend of sinners, but the gospel is the only truth worth believing. It tells us that the best is yet to come.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Asterix holds out