The end of the tridentine paradigm (or Where is the Roman Catholic Church going)?

The first results of the “synodal process” in European dioceses are attacks on the Tridentine paradigm.

05 DECEMBER 2022 · 16:25 CET

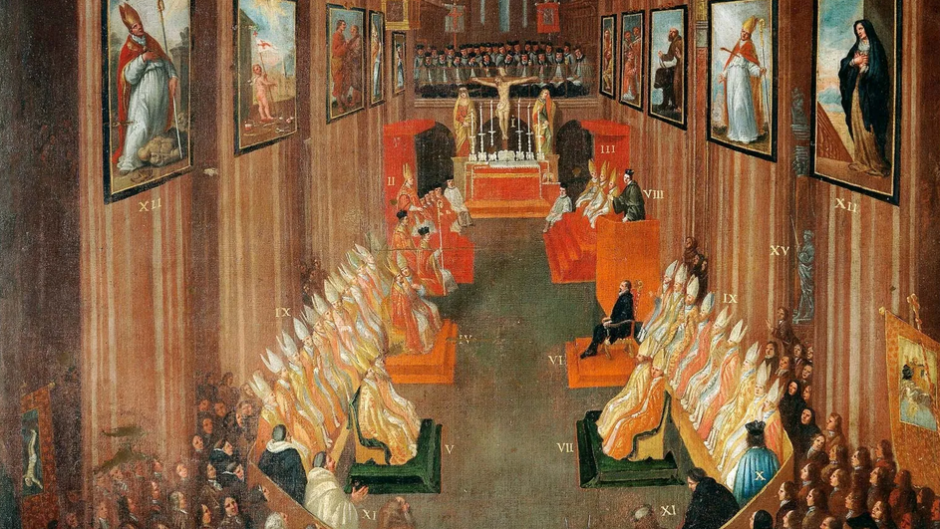

It was the historian Paolo Prodi (1932-2016) who coined the expression “Tridentine paradigm” to indicate the set of identity markers that emerged from the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and which shaped the Catholic Church for centuries, at least until the second half of the 20th century.

In one of his most famous books, Il paradigma tridentino (2010), Prodi explored the self-understanding of the institutional church of Rome which, in the wake of and in response to the “threat” of the Protestant Reformation, closed hierarchical and pyramidal ranks up to the primacy of the Pope.

The church consolidated its sacramental system, regimented the church in rigorous canonical forms and parochial territories, and disciplined folk devotions and the control of consciences.

It relaunched its mission to counter the spread of the Reformation and to anticipate the Protestant states in an attempt to arrive first in countries not yet “evangelized.”

It promoted models of holiness to involve the laity emotionally and inspired artists to celebrate the new vitality of the church of Rome in a memorable form.

The Tridentine paradigm produced the Roman Catechism of Pius V (1566) as a dogmatic synthesis of the Catholic faith to which Catholics scrupulously had to abide, the controversial theology of Robert Bellarmine to support anti-Protestant apologetic action, and the great baroque creations by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (like the majestic colonnade of St. Peter’s) to represent the church as the winner over its adversaries and new patron of artists and intellectuals.

The Tridentine paradigm has withstood the challenge of the Protestant Reformation and more.

With the same paradigm, Rome also faced a second push coming from the modern world: that of the Enlightenment (on the cultural side) and the French Revolution (on the political side) between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

With the same set of institutional, sacramental, and hierarchical markers that emerged from the Council of Trent, Rome defended itself from the attack of modernity and counterattacked.

With the dogmas of the immaculate conception of Mary (1854) and papal infallibility (1870), which are children of the Tridentine paradigm, Rome elevated Mariology and the papacy to identity markers of modern Roman Catholicism.

With Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors (1864), Rome condemned the modern world, just as the Council of Trent had anathematized Protestants.

With the encyclical Aeterni Patris (1879), Leo XIII elevated Thomism to a system of Catholic thought against all the drifts of modern culture.

The Tridentine paradigm exalted the church of Rome and condemned its enemies. It established who was in and who was out. It defined Roman Catholic doctrine and rejected “Protestant” and “Modernist” heresies.

It solidified Roman Catholic teaching and consolidated practices. It authorized controlled forms of pluralism but within the compact structure of the central organization.

According to the Tridentine paradigm, it was clear who Catholics were, what they believed, how they were expected to behave, and how the church functioned.

Then, the world changed, and Roman Catholicism changed with it. The Tridentine paradigm gradually eroded with the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), not in a frontal and direct way, but following the path of “development” and “aggiornamento” that Vatican II promoted.

Of course, Rome does not make any U-turns or swerves sharply. Trent is still there, and the dogmatic and institutional structures of the Tridentine paradigm are standing.

The Roman Catholic Church has begun to see its limits, wishing to overcome them by embracing a new posture in the world.

Even if Paul VI immediately saw the risks of abandoning it, John Paul II tried to make the Tridentine paradigm elastic by extending it to the universal church.

Benedict XVI coined the expression “reform-in-continuity” to try to explain the Catholic dynamic of change without breaking with the past.

The pope who seems to perceive the Tridentine paradigm in negative terms is Pope Francis. His invectives against “clericalism” are directed at Roman Catholic people and practices nourished by the Tridentine spirit.

The typical distinctions of the Tridentine paradigm are rendered fluid and are progressively dissolved: clergy/laity, man/woman, Catholic/non-Catholic, heterosexual/homosexual, married/divorced, etc.

If the Tridentine paradigm distinguished and selected things and people, Francis wants to unite everything and everyone. The first paradigm separated Roman Catholicism from the rest; this pope wants to mix everything.

The first worked with the pair white/black, inside/outside, faithful/infidel. Francis sees the world in different shades of gray and welcomes everyone into the “field hospital” that is the church.

The “synodal” church dear to Francis seems to overturn the traditional pyramidal structure. The direction of the church is determined by the “holy people of God” made up of migrants, the marginalized, the poor, the laity, and people in irregular life situations.

Before there were heretics, pagans, and excommunicated, now we are “all brothers”. It is no longer the center that drives, but the peripheries.

It is not sin, judgment, and salvation that occupy the discourse of the church, but its message today touches on themes such as peace, human rights, and the environment.

The church no longer wants to present itself as a “magistra” (teacher) but only as a “mater” (mother).

With its calls for the extension of the priesthood to women and the blessing of same-sex couples, the German “synodal path” is effectively striking the Tridentine paradigm.

The first results of the “synodal process” in European dioceses are attacks on the Tridentine paradigm.

It is true that there are conservative circles (in the USA in particular) who claim the Tridentine paradigm and would like to revive it. However, the point is that Roman Catholicism globally is at a crossroads.

Has the Tridentine paradigm reached the end of its journey? If so, what will be the face of Roman Catholicism tomorrow?

Neither the Tridentine paradigm nor the various synodal paths dear to Pope Francis indicate an evangelical turning point in the Church of Rome. The Church of Rome was and remains distant from the claims of the biblical gospel.

Leonardo De Chirico is an evangelical pastor in Rome (Italy). He is a theologian and an expert in Roman Catholicism. He blogs at VaticanFiles.com.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Vatican Files - The end of the tridentine paradigm (or Where is the Roman Catholic Church going)?