The paradox of Vincent van Gogh

His own writings to Theo and his paintings of his latter phase bear witness to his preoccupation to the end with the person of Christ.

19 OCTOBER 2017 · 12:20 CET

Across the road from the YWAM centre De Poort on the Amsterdam harbourfront, and next door to the shipping museum, is the long red-brick former admiralty building.

A large bronze plaque can be seen on the building from the windows of De Poort, where we held the Masterclass in European Studies earlier this month.

Closer inspection shows it to commemorate, not the brave career of some heroic naval officer, but the sojourn in that building of a young, zealous theology student named Vincent van Gogh.

Lodging there from May 1877 to July 1878, with his uncle, Rear Admiral Johannes van Gogh, Vincent tried unsuccessfully to prepare for theological study, tutored by another uncle, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church.

Sundays for Vincent involved a self-imposed routine of fanatical church attendance: an early morning service in the Oosterkerk nearby, followed by another in the Oudezijds Kapel (to this day an evangelical ministry in the red light district).

Walking further to the next sermon in the Westerkerk, he concluded his circuit in the Norderkerk. The bronze plaque cites his own words to his brother Theo about the ‘many church porches and floors’ he had seen in the city.

Failure at his studies led to departure to a poor mining district in Belgium as a lay preacher. With the same fanaticism, he involved himself in the lives of the poor, gave away all his belongings and even went down into the mines. But his efforts were rejected by both the locals and the mission for whom he was working.

Rejection

His sketches of the bleak, poverty-stricken Borinage however prompted Theo to advise him to become an artist. But this new search for his calling was also fraught with disappointment, rejection and failure. He wrote to Theo that he would ‘never amount to anything important’.

Further failure (including an ill-fated attempt to help a prostitute and her child) forced him to move back in with his parents in Nuenen, near Eindhoven, in the south of the Netherlands. There he produced over 500 works in earthy colours or pencil, mostly of peasant scenes.

Then France beckoned, firstly to Paris where he discovered colour and developed his typical, short brush stroke style, and later to Arles in the south where he had hoped to set up a brotherhood of artists.

There his tempestuous relationship with Paul Gauguin led to a year in an asylum and the production of another 150 works. The final year of his life, 1889-90, Vincent moved to Auvers-sur-Oise to be closer to his brother. His frantic artistic activity continued, yielding a painting a day.

One day in July 1890, he staggered back from a cornfield with a fatal gunwound. He died two days later.

Until recently, it was assumed he had shot himself. But questions about the angle of the shot and other circumstances have now led to theories that local youths were responsible.

The tragically-short life of Vincent van Gogh was one of paradox upon paradox. During his prolific decade of artistic production before he died, he struggled to sell his paintings. Yet today his works sell for hundreds of millions of euros.

Evidence

His association with Amsterdam was never as a painter. Yet today one of Amsterdam’s most popular tourist attractions is the Van Gogh Museum, where fans line up every day outside, eager to see the collection of over 200 of his originals.

Critics traditionally have assumed van Gogh’s disappointments with the church led him to break with institutional Christianity and to seek the divine in nature. Yet his own writings to Theo and his paintings of his latter phase bear witness to his preoccupation to the end with the person of Christ: “… a greater artist than all other artists, despising marble and clay as well as colour, working in living flesh,” he wrote. “This matchless artist … made living men, immortals.”

Two books which had a lifelong impact on van Gogh were The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas a Kempis, and Pilgrim’s Progress, by John Bunyan. About his 1890 painting of an old man sitting by a fireplace, called At Eternity’s Gate, he wrote: “One of the strongest pieces of evidence for the existence… of a God and an eternity, is the unutterably moving quality that there can be in the expression of an old man… that can’t be meant for the worms.…”

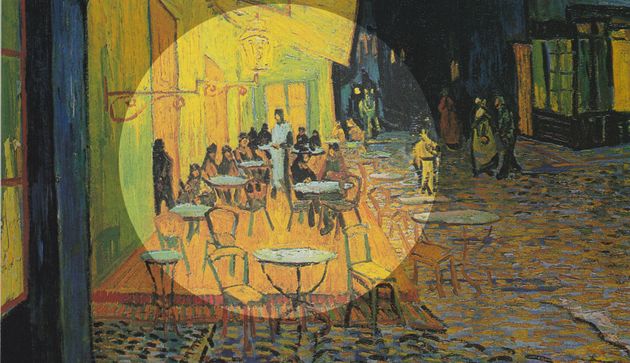

Most recently, my eight-year-old granddaughter–a committed Vincent fan–made me aware of new research declaring Café Terrace at night (1888) to depict the Last Supper, complete with a shadowy Judas slipping out the door, a central Jesus-figure with a cross behind him, and the remaining disciples seated at the tables.

The whole scene is bathed in a golden-yellow hue, van Gogh’s typical allusion to the divine.

Writing to Theo about this work, Vincent said he felt a “tremendous need for, shall I say the word—religion.”

Jeff Fountain is Director of the Schuman Centre for European Studies, and speaks on issues facing Christians today in Europe. He writes at Weekly Word.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Window on Europe - The paradox of Vincent van Gogh