Was literacy widespread in Ancient Israel?

It is very important to answer this question, especially if one wants to argue for the possibility of the existence of a written Torah prior to 1000 BCE.

05 FEBRUARY 2018 · 12:20 CET

Was literacy widespread in ancient Israel or was it only confined to scribes or elite segments of society?

Looking at epigraphic evidence is very important to answer this question, especially if one wants to argue for the possibility of the existence of a written Torah prior to 1000 BCE.

Most skeptics argue for the view that most of the Old Testament was written during or shortly after the Babylonian exile. But what does archaeology suggest about the writing habits of Iron Age Israel, and most importantly, is it possible to argue for an earlier writing date? In this article, we will be looking into a few epigraphic Iron Age examples…

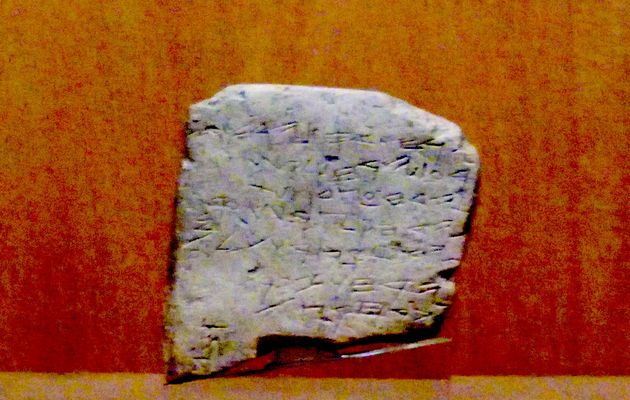

THE GEZER CALENDAR

The Gezer Calendar, discovered in 1908 in the ancient city of Gezer by Irish archaeologist R.A. Macalister, is one of the oldest Hebrew scripts ever discovered. The inscription is being displayed in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, and many experts date this limestone inscription to around 925 BCE. To put this date into perspective, this would be only a few years after King Solomon’s death.

The calendar is written in the Paleo-Hebraic script, which is very close to the ancient Phoenician script and is a precursor to modern Hebrew. In the tablet, one can observe 7 horizontal lines. These lines delineate the epoch of the year for different agricultural activities:

(1) Two months, late crops — Two months,

(2) Sowing — Two months, spring crops —

(3) One month, cutting flax —

(4) One month, harvest of barley —

(5) One month, all the harvest —

(6) Two months, fruit vines —

(7) One month, summer fruits

An eight damaged vertical line does exist in the bottom left-hand corner. It spells out “Abi—”. This is most probably what appears to be the name Abijah (or Abi-yahu). Most possibly it is the signature of the person who wrote the calendar.

Since the calendar script seems to be very messy and haphazardly chiseled, a few possible line of reasoning have emerged as to its origin. One theory claims that this was written by a farmer who had just learned to read and write.

Perhaps, this tablet was a way for this person to display his new writing skill. Another possible explanation is that this tablet was perhaps a writing exercise for children or a way for children to learn about the agricultural cycle, a sort of ancient life sciences textbook.

This discovery is important because of its location in the countryside. If one were to argue for the literacy of the elite, one would expect to find more exemplars from the cities as opposed to the countryside.

Since the discovery of this inscription, at least have a dozen more inscriptions have been discovered in the countryside which suggests that literacy was more widespread among the lower classes than previously thought.

Additionally, I have trouble believing that a people group who were recording or teaching their agricultural activities to children, would not be recording their own history at the same time. After all, the Old Testament is an ancient record of Israel’s history!

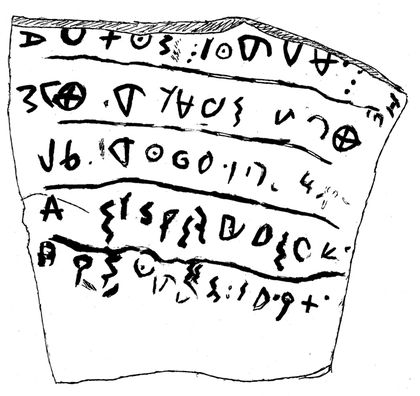

THE QEIYAFA OSTRACON

Another inscription that dates to the 10th, perhaps even 11th century BCE is known as the Queiyafa Ostracon which is being displayed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. Discovered in 2008 at the ancient ruins of Khirbet Qeiyafa, this inscription is also written in Proto-Hebraic.

There are a couple of possible translations of this inscription. The two most prominent translations include words such as king, judge/judgment, widow, orphan poor.

According to Émile Puech of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française, this inscription presents a transition period between the period of the Judges and the period of Kings, perhaps reflecting the epoch of king Saul himself! The translation suggested by Peuch is as follows:

(1) Do not oppress, and serve God … despoiled him/her

(2) The judge and the widow wept; he had the power

(3) over the resident alien and the child, he eliminated them together

(4) The men and the chiefs/officers have established a king

(5) He marked 60 [?] servants among the communities/habitations/

The second alternate translation is that of Gershon Galil of Haifa University:

(1) you shall not do [it], but worship (the god) [El]

(2) Judge the sla[ve] and the wid[ow] / Judge the orph[an]

(3) [and] the stranger. [Pl]ead for the infant / plead for the po[or and]

(4) the widow. Rehabilitate [the poor] at the hands of the king

(5) Protect the po[or and] the slave / [supp]ort the stranger.

Galil’s translation is very fascinating, as it captures the prophetic style we are used to seeing in Biblical writings. Contrary to neighboring cultures, in this script, we do not see the glorification of gods or an emphasis on taking care of the needs of such gods.

Rather, we see a call to take care of the widow, the orphan and the destitute. Galil also identifies the location of Khirbet Qeiyafa as the “Neta’im” mentioned in 1. Chronicles 4:23.

The reason for this is that the archeological site of Khirbet Qeiyafa is rather close to Khirbet Judraya (Gedera). The people of both of these locations were known as "potters" who were "in the service of the king". This definition matches quite well with the amounts of pottery that have been discovered on the site.

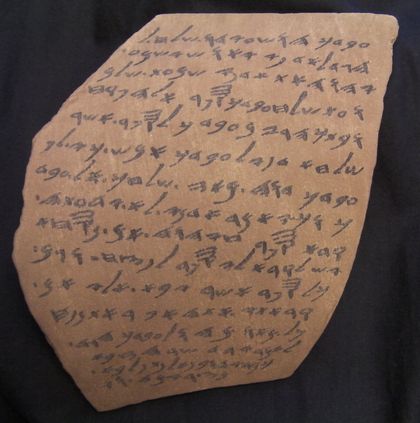

THE LACHISH LETTERS

The Lachish letters date from around 590 BCE. Even though this is a late example, it is an important one because it shows us that writing was widely used among soldiers and military personnel also. The Lachish letters contain messages sent between different military outposts in Judah prior to the Babylonian conquest of the Kingdom of Judah.

A total of 9 letters were discovered in 1935 by J.L. Starkey and are currently being displayed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and the British Museum in London. The letters reflect a dialog between Yaush, possibly the military commander at Lachish, and Hoshaiah, who probably manned an outpost nearby.

These letters were written shortly before Lachish fell to Nebuchadnezzar II during the reign of King Zedekiah of Judah. The letters contain both formal reports about the war and also a list of materials or goods needed for the outpost. Letter 3 is especially interesting since it contains instructions by an unnamed prophet. Here are a few examples:

(Letter 3) The commander of the army Konyahu son of Elnatan, has gone down to go to Egypt and he sent to commandeer Hodawyahu son of Ahiyahu and his men from here. And as for the letter of Tobiyahu, the servant of the king, which came to Sallum, the son of Yaddua, from the prophet, saying, "Be on guard!" your ser[va]nt is sending it to my lord.

(Letter 4) I wrote on the sheet according to everything which [you] sent [t]o me. And inasmuch as my lord sent to me concerning the matter of Bet Harapid, there is no one there. And as for Semakyahu, Semayahu took him and brought him up to the city. And your servant is not sending him there any[more ---], but when morning comes round [---]. And may (my lord) be apprised that we are watching for the fire signals of Lachish according to all the signs which my lord has given, because we cannot see Azeqah.

(Letter 9) May YHWH cause my lord to hear ti[dings] of peace and of [good. And n]ow, give 10 (loaves) of bread and 2 (jars) [of wi]ne. Send back word [to] your servant by means of Selemyahu as to what we must do tomorrow.

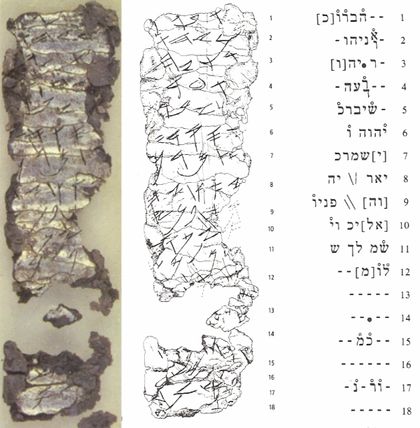

KETEF HINNOM

Discovered in 1979 in Jerusalem, in an iron age burial site close to St. Andrew’s church. The Ketef Hinnom silver scrolls contain perhaps the oldest citations ever discovered of the Old Testament.

The two tiny scrolls, which are currently being displayed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, measure 27x97 mm. and 11x39 mm. respectively and date from the late 7th century BCE.

Both of these scrolls were found in clay pots next to burial sites an were most likely prayers of benediction for the soul of the dead who would be passing away to Sheol.

The smaller of these two scrolls contain a citation of the priestly benediction found in Numbers 6:24-27. Lines 5-12 read as follows:

(5) May bless you, (6)YHWH, (7) keep you. (8) Make shine, YH- (9) -[W]H, His face (10) [upon] you and g-(11)-rant you (12)p-[ea]ce.

The larger of the two scrolls contain a phrase in its first 6 lines which also appear in Exodus 20:6 and Deuteronomy 5:10. Lines 7 through 14 contain phrases reminiscent of the Psalms of David (see Psalm 18:2). Lines 14 through 18 contain another version of the priestly benediction:

(1) […] YHW…(2) […] (3) the grea[t ... who keeps] (4) the covenant and (5) [G]raciousness towards those who love [him] and (6) those who keep [his commandments]. (7) […] (8) the Eternal? […] (9) [the?] blessing more than any (10) [sna]re and more than Evil. (11) For redemption is in him. (12) For YHWH (13) is our restorer [and] (14) rock. May YHWH bles[s] (15) you and (16) [may he] keep you. (17) [May] YHWH make (18) [his face] shine...

CONCLUSION

The Ketef Hinnom in of itself completely debunks the idea that the Old Testament and specifically the Torah may have been written during or shortly after the Babylonian exile. Citations like this from the late 7th century BCE suggest that a written text existed at least prior to the 8th century BCE.

Given the iron age epigraphic evidence; we know that writing was widely spread in the countryside, that outside of scribes literacy also existed among different classes like farmers and soldiers, and that some of the inscriptions reflect a prophetic tone similar to what we find in the Old Testament text.

All this, to me, is evidence for the existence of a written Old Testament tradition prior to the 10th or 11th century BCE.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Arnold, Bill T; et. Bryan E. Beyer. Readings From the Ancient Near East. Baker Academic, 2002. p. 168.

- Barkay, Gabriel, et al., The Challenges of Ketef Hinnom: Using Advanced Technologies to Recover the Earliest Biblical Texts and their Context. Near Eastern Archaeology 66, 2003, pp. 162-171.

- Khirbet Qeiyafa identified as biblical “Neta’im. The University of Haifa. 4 March 2010. http://newmedia-eng.haifa.ac.

- Leval, Gerard. Ancient Inscription Refers to Birth of Israelite Monarchy. Biblical Archaeology Review, May/June 2012, pp. 41-43.

- Mitchell, T.C. The Bible in the British Museum: Interpreting the Evidence. The British Museum Press 2013.

- Pasinli, Alpay. Istanbul Archaeological Museums. A Turizm Yayinlari. Istanbul, 2012, pp. 169-170.

- Rollston, Christopher A. What’s the Oldest Hebrew Inscription?. Biblical Archaeology Review, May/June 2012, pp. 32-40, 66, 68.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Archaeological Perspectives - Was literacy widespread in Ancient Israel?