How do we treat our enemies?

The main character in “Bridge of Spies” not only believes in the power of the word, but also seeks to identify himself with the other, with the enemy.

20 SEPTEMBER 2016 · 17:00 CET

Some walls seem unsurmountable. Those of us who grew up during the Cold War know of that paranoia that becomes fear. I have spent the last few days in Germany – speaking about Spanish reformers at a conference for European evangelical theologians in Wittenberg–, and I spent my evenings watching the series “Deutschland 83”. 1983 was the year that I started studying German at the Complutense University in Madrid, drawn by a passion for the culture of that country. At that time, the places in which the Reform had grown up were behind the Iron Curtain.

Spielberg’s “Bridge of Spies” is now out on DVD. It is an unusual film in that it seems to be taken from a different era. It has the feel and rhythm of the films from the time when the industry wasn’t just churning out the vacuous entertainment served up to adolescents nowadays, but when films were used to depict complex individuals. The mastery that Tom Hanks displays in playing the Brooklyn lawyer, James Donovan, caught up in the bowels of the Cold War, demonstrates that an actor is somewhat more than just someone that plays themselves. They are recreating a character – in this case, a historical character –, without the reductionism that resorts to a 2D caricature.

The acclaimed New York critic, Richard Brody, detects something of Spielberg himself in the character of James Donovan. Many have accused Spielberg of closing down the new Hollywood that appeared at the end of the sixties, with large studios making films of the dark ilk of “Easy Rider”, “The Godfather”, “Chinatown” or “Taxi Driver”. The fact of the matter is that “Jaws” continues to be one of the most studied films in the history of cinema. Spielberg succeeded in playing with the rules of the game, with a tact and dexterity, not lacking empathy or bonhomie, that has won the respect of directors as far apart from him as Scorsese or Paul Thomas Anderson.

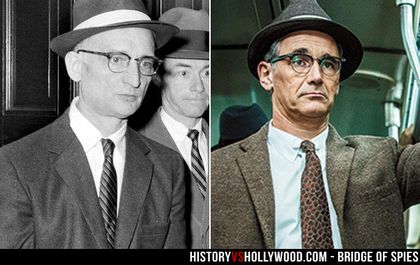

The film’s opening scene has received wide praise from critics due to its ingenious expressivity. A panoramic shot shows us a painter in its centre. He is putting the finishing touches to a self-portrait with his back to the spectator. To the left, we see his face in the mirror, where he is studying his features and looking back at us. We see two reflections of the man, in the mirror and in the painting. This is the towering British actor, Mark Rylance, playing a supposed Russian spy, who then tries to escape in a riveting chase scene in the New York metro, reminiscent of some of the films of the 1960s, such as “French Connection”.

UNFOLDING

The unfolding of the character of Rudolf Abel, accused of espionage by the CIA – something that he never admits to –, introduces us to a double life that makes these kinds of stories so interesting. Along with so many others, Spielberg is a great admirer of “The Spy Who Came in from the Cold” (1965), the film by Martin Ritt based on the book by John Le Carré, played by a complex Richard Burton. In his opinion, it is not only the best adaptation of a Le Carré book, considered by Graham Greene as the best spy novel, but it is his favourite spy film of all time.

My own passion for spy stories began when I was a teenager, when the distance between one’s image and the internal world that we try to hide increases exponentially. As the Spanish author Javier Marias has observed, spies embody the duality of Man. They fascinate us because they are not what they appear to be. Behind the boring grey life of an insurance lawyer, as in Donovan’s case, there is a dark and complex world, where nothing is as it seems. Spy stories ask us who we are, what our truth is, and they question our ideas about loyalty and innocence.

Donovan is no angel. Tom Hanks introduces him to us trying to divide the insurance compensation of a driver involved in a car accident between the five people that have suffered damages, and who should all receive the same amount. It is on same terms that he tries to preserve the life of his client, seeking a possible exchange for an American prisoner on the other side of the Iron Curtain. He is someone who bends the rules to achieve his own ends. He isn’t the devoted family father that we imagine at the start of the film. When his house is shot at, he goes to comfort his daughter, played by Bono’s daughter (Eve Hewson), but she instead runs into the arms of her mother (Amy Ryan), a wife in the style of Donna Reed in the Hollywood classics.

ENEMIES

I don’t know whether Spielberg’s film is all about Guantánamo, but it shows that humanity is expressed in the way in which we treat our enemies. As Jesus says, there is nothing particularly special in being good to our own people, speaking well of people who think like ourselves, and being generous to our friends. We naturally love those who love us, but the love that God shows us in Jesus Christ, reaches out to the enemy, walks the extra mile, presents the other cheek and seeks peace, giving our own lives for others (Matthew 5:38-48).

The main character in the “Bridge of Spies” not only believes in the power of the word, but also seeks to identify himself in the other, in the enemy. The Christianity of Jesus does not trust in violence either, but in the power of the Spirit to work through the Word, the change that makes it possible to love the enemy. Discovering this and our own nature, sinners like everyone else – no better than others –, we can identify with those who in principle only elicit our rejection. We pity them and are able to love them, through the supernatural working of God’s Spirit.

This is what God did with us, when he came to Earth. By becoming man, he “endured such opposition from sinners” (Hebrews 12:3), whereby nothing human is foreign to him. He knows all our weaknesses, even though he was faultless. He can identify himself with us and knows what we think and feel. That is the marvel of his becoming man, something that no other religion professes and makes Christianity different to Jewish and Greek thinking. So if our faith doesn’t bring us to identify with others, or feel compassion for them, we have to question whether we are behaving like the disciples of our Teacher

Why do Christians show so much rejection and aggression? You only need to surf the social media to see the offensive language that Christians use against anyone who swerves of the straight and narrow. The defenders of sound doctrine often behave like fanatics, full of hatred and intolerance for anyone who does not think like them. When someone leads a life that is not in line with the Christian faith, they immediately threaten them with divine judgement and eternal condemnation. They have no qualms in contradicting people’s professions of faith on the basis of simple appearances or personal impressions. If on top of all this these people should declare themselves atheists or satisfied with their unchristian behaviour, they will only receive invectives…where is the love for our enemies in all this?

GRACE

If we defend that which is just, we will have enemies. We can justify our hostility, but Jesus says: “But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be children of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked.” (Luke 6:35). Our love needs to be more than just pretty words. It should be demonstrated in practice. Though you may say that you love homosexuals, albeit rejecting their way of life, if your attitude is no more than judgment and condemnation, I don’t know where the love is in your words. If your political convictions are so rigid that you can’t help denigrating those who don’t think like you, your ideology is one of hatred and not of love for your fellows. When we have good relations with the authorities because we want something in exchange, we are not contributing in any way but simply awaiting our reward. Love has a cost and that is not to expect our reward in this world.

The enemy has the power to take away but not to give back. Jesus does. His future is in His hands, not in theirs. In His undeserved love, He promises us the prize that the world cannot give. He is patient and merciful with us. We see his goodness time and again in that, despite our perversity and ungratefulness, he has given himself for us until the end, giving up His only Son to die on the cross. That is how we should love our enemies.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - How do we treat our enemies?