The Jewish composer of the Reformation Symphony

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) converted to Christianity when he was young, going on to become one of the foremost Protestant composers.

16 DECEMBER 2016 · 12:32 CET

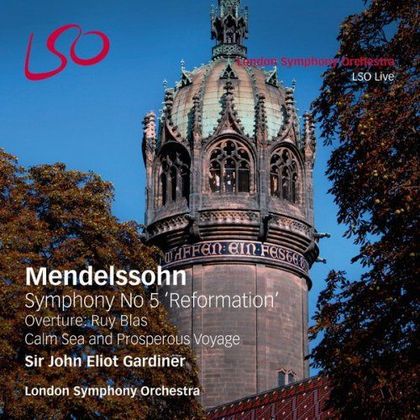

Now that Luther’s anti-Semitism is attracting so much attention, it seems all the more striking that the composer of the Reformation Symphony, should have been a Jew, Mendelssohn (1809–1847). He wrote it for the anniversary of the Conference of Augsburg in 1830. Even though he was born into a Jewish family, he converted to Christianity, and went on to become one of the foremost Protestant composers. He arranged Bach’s St Matthew’s Passion and his evangelical faith took him to compose an oratorio on Paul, using only biblical text, and on Elijah.

A few years ago, a Czech writer called Jiri Weil wrote a novel entitled “Mendelssohn is on the Roof”. He tells the story that during the Nazi occupation of Prague, an SS official received an order to remove Mendelssohn’s statue from the roof of a concert hall. The problem was that the roof was full of statues of different composers, and he had no means of identifying them. The Nazi official remembered that in their “racial science” classes on Jews, they had been told that Jews had large noses. He therefore decided to remove the statue with the biggest nose, but it turned out to be the very Wagner who had said that, regardless of being a Lutheran, Mendelssohn continued being a Jew. On account of this, his music was banned by the Nazis.

A CONVERTED JEW

Like Mozart, Mendelssohn was a prodigy child. His first public performance on the piano came at the age of nine, and he started composing music the following year. Educated by his mother in an exquisite and refined culture, he mastered Latin and Greek, as well as being able to paint and draw with accomplishment. He was a good sportsman, but he particularly excelled in music. He played the piano and the organ with great mastery, but he was also excellent on the violin and the viola. At the age of sixteen he wrote his enchanting overture for Shakespeare’s “Midsummer night’s dream”. Some people think that he never surpassed his genius in that romantic piece.

His family moved to Berlin in 1912, where Felix studied with Carl Zelter, who had links to the Bach family and who introduced him to an elderly Goethe. From a young age, Felix was very close to his sister Fanny, a renowned pianist and composer, who published several of her own compositions under Felix’ name. He was a contemporary of Hegel at the University of Berlin, studying aesthetics, geography and history. His memory was so impressive that the story goes that once, when he arrived to play his overture to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in England, he realised that he had left the music in a car, so sat down and rewrote the whole piece from memory then and there.

At the age of twelve he was already studying Bach’s St Matthew Passion in the Royal Library of Berlin, where a manuscript was kept. His mother gave him a copy for his birthday, made especially for him, since it had not yet been published. Eight years later he presented it in Berlin, in one of the greatest events in the history of music. He conducted the music again for Bach’s birthday on 21 March 1829, having by then become a famous conductor at the age of twenty.

THE JOY OF LIVING

Sigmund Spaeth once observed that it was a relief to find a musician who was really happy for most of his life, even though Mendelssohn’s was so short. Most of great composers seem to have had difficult characters. But this does not seem to have been the case for Mendelssohn. According to most witnesses, he was a modest man with a joyful nature – as his name would suggest –, albeit somewhat nervous.

He married the daughter of a French Protestant pastor, Cecile Jeanrenaud, with whom he had five children. While he was extroverted, she was rather reserved, but they got on well. She painted, while he composed his music. He was however so passionate that he sometimes became excited to the point of suffering collapses, like the one that caused his death at the age of 38, shortly after which his wife also died. They were only married for ten years.

Many people have wondered where Mendelssohn got that energy that filled him with that strange joy of living. For him, “the Bible was the best thing”. That is what he said when he composed his oratorio on Paul, based on the biblical text and Bach’s chorales. He loved the Scriptures so much that his words resound with a strength – there and in his piece on Elijah –, that many compare it with an act of public worship. His music is a true celebration of faith.

His favourite singer was the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, whom he met in 1844. He wrote some of his work for her, but she retired when she was at the top of her career. Mendelssohn’s biographer, Philip Radcliffe tells that a friend asked her why she was retiring from music at that point, and she answered: “What else can I do when every day it made me think less of the Bible?”.

FORTRESS

Mendelssohn is famous for his wedding march, his short and intimate pieces for piano known as his “Songs without words”, his popular Violin Concerto in E minor (recorded by Anna Sophie Mutter for Deutsche Grammophon for his 200 year anniversary) and his “Scottish” and “Italian” symphonies. Protestants remember him however in particular for the music he wrote in commemoration of the 300 years of the Augsburg Confession. His “Reformation Symphony” ends with Luther’s hymn “A Mighty Fortress is our God”, based on the words of Psalm 46, which contains this glorious declaration from the Reformer:

God's Word forever shall abide,

no thanks to foes, who fear it;

for God himself fight by our side

with weapons of the Spirit.

Were they to take our house,

goods, honour, child, or spouse,

though life be wrenched away,

they cannot win the day.

The kingdom's ours forever!

On his tomb in the Berlin-Kreuzberg Holy Trinity Cemetery is marked out by a large white cross. At his funeral, six hundred voices sang: “Christ and the Resurrection”. Following various attacks, Felix left this world, six months after his sister Fanny – who suffered, like her parents and grandparents, of apoplexy–. In his last years, he suffered from ill health, from nervousness or too much work, but he kept his faith until the end.

Although the Nazi’s saw him as just another Jew, whose statue in Leipzig they should remove and whose descendants they had to expel, they were not able to destroy the Word that gave him strength and joy in life. They closed down the family business, demolished his statue, but despite it all and “though life be wrenched away, they cannot win the day. The kingdom’s ours forever”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The Jewish composer of the Reformation Symphony