The honesty and crisis of Francis Schaeffer

In search of authenticity (2): In Schaeffer´s view what differentiates Christianity from any other religion, is that "God did everything"

03 AUGUST 2017 · 11:20 CET

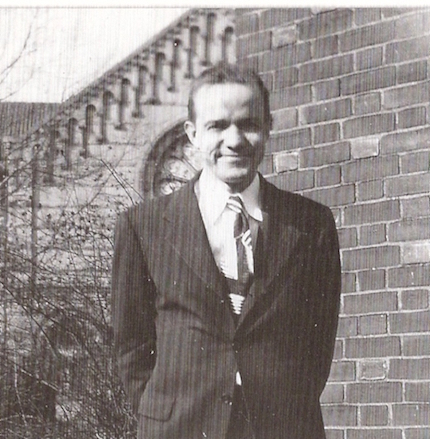

There are books you don´t just read, they actually grip you! That´s what happened to me in the late 70's, when I read Francis Schaeffer´s (1912-1984) "True Spirituality". If you read the preface I´m sure you´ll want to continue reading ...

"Many years had passed since I had been converted from agnosticism to Christianity. Then I was pastor for ten years in the United States and after that I worked in Europe for several years together with my wife Edith. During this period I felt the need to defend the position of historical Christianity as well as the purity of the visible church, very intensely.

However, I gradually faced a new problem; staying in touch with reality. In the first place, it seemed to me that many of those who held an orthodox position were disconnected from reality. Secondly, I noted my own failure to connect with reality. "

THE NEW FUNDAMENTALISM

To understand Schaeffer´s 1950s crisis we have to understand its origins. As I mentioned in the first article, he had not only converted to the Christian faith, but entered into an evangelical movement which distanced him from the nominal Protestantism of his parents.

This is how he became part of the historical fundamentalist movement represented by the elder Machen and his critique of liberal theology, forming the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and the Westminster Seminary in Philadelphia.

But this was not enough. Schaeffer opted for the new fundamentalism as we know it, by entering the Bible Presbyterian Church and the Faith Theological Seminary of the fierce young McIntire ... but what differentiates the two?

Neo-fundamentalism is a movement which advocates a separation of second and third degree, i.e. separation from anyone who is "guilty by association" and who has not distanced himself from those who have not become separate from the world.

His extreme position even takes him as far as being unable to distinguish a classic doctrinal position, such as the Augustine tradition. Neo-fundamentalists hold that one´s position on the millennium or on baptism is as important as the doctrine of salvation.

Above all, it embraces a holiness, which is not only characterized by no smoking or drinking, which was acceptable in Westminster, but by it’s distancing from the world and its social entertainments. Although this clashed with Schaeffer's interest in art and culture, he accepted it and even Edith stopped dancing, although she had done so in high school.

We have to distinguish clearly between both fundamentalist positions to avoid a lot of confusion. The issue at stake in this case is not what the value of “sound doctrine” is but more “what does sound doctrine really mean?” Does it refer to the fundamental truths of Christianity or does it mean “any belief that one considers biblical”?

The most important thing to bear in mind is where does our responsibility lie in this bone of contention? Should you devote your life to shooting everything that moves or do you simply live your faith and proclaim the essential truths of the Gospel?

In practice, what does being a Christian really mean? Is it to become your neighbours’ judge or is it more about true freedom? And finally, how does relate to the world at large? Is this only about spiritual matters? Or does it have to do with daily living?

If there is something that characterizes Schaeffer´s thinking, it is the search for authenticity, which is the title of the book by Duriez, now published in Spanish by Andamio. In it we discover someone who examines himself honestly and asks himself the questions that others take for granted.

Christian language is full of presuppositions that no one recognizes, apart from those who use them, a jargon which is completely foreign to the unbeliever and no longer means anything even to Christians. They are holy sounding phrases which vary depending on ambience and fashion, but they can be considered biblical in appearance only.

All of Schaeffer´s preconceptions came down with a crash during his time in the mountains of Switzerland in the early 50's. The question everyone asks is: what happened to him? Having read much of what he wrote and comments published on it over the years, I can only say that there´s no easy answer that question...

CRISIS, WHAT CRISIS?

It has struck me that no biographer deals with Schaeffer´s middle- age period. At this stage in life, I can honestly say that I don´t have such a black and white view of things as when I was a younger man who was more prone to extreme points of view than when I reached forty.

Of course there are people who get bogged down at that stage, but by the 1950´s Schaeffer had reached the middle age crisis period which is when we all tend to ask ourselves who we are and what we may have let slip by along the way.

His use of intellectual language gives you the wrong impression because his son-in-law describes him more as a rather emotional type of person. It is not unusual for people to get the impression that he had suddenly embraced atheism. His doubt is so deep rooted that it seems he questions the very existence of God and Christianity´s fundamental truths. I don´t think this was the case, because when he talks about these doubts it is in the preface to his book on "True Spirituality" (1971), not in the prologue to "God is there" (1968).

Although his book was not published until the early 1970s, there were many previous drafts. His problem with editors is that he wanted to keep the verbal style of these talks. The first time he spoke of these issues was at a camp for Presbyterian missionary families in the United States in 1953, but his reflections do not take their current format until he presents them to the community that he forms in L´Abri,Switzerland, by then it was 1964.

The first article that we can find is published in 1951, not within the separatist circle of magazines like The Bible Today or The Beacon, but in a general publication for Sunday schools called Sunday School Times.

This was a reality which he, the great champion of orthodoxy, discovered was lurking within his own heart. His family recalls that such a discovery led him into a depression where he battled against anger and frustration. He wasn´t judging the Bible, he was judging his own Christianity. His doubts weren´t doctrinal, they were personal.

THE FINISHED WORK OF CHRIST

On the one hand, there is a clear freeing from legalism. As we have said, the neo-fundamentalism in which Schaeffer had been formed was full of rules of separation and purity, and did not allow any room for freedom of conscience.

His daughter Susan - married to my friend Ranald Macaulay - recalls how, when she was 10 years old in 1951, saw her father drink wine for the first time - they didn´t even use it to celebrate the Lord´s Supper! -. It was not so much that he began to smoke and drink, but simply that he didn´t mind others doing it.

At L´Abri - we will discuss this community in the next article – you couldn´t use drugs, but as we shall see, he accepted many young drug users. He didn´t confront their problem morally but existentially. In Schaeffer´s view "lost souls are recovered by the reality of the existence of the Creator," and not by a new form of legalism.

In that sense, the study of the Epistle to the Romans was vital and was probably the book of the Bible that he most regularly taught on at the community and in conferences.

The expression most repeated by him at that time was "the finished work of Christ." Schaeffer discovered that Christianity is not a system of values, as is often thought, but a life which is based on "the substitutionary work of Jesus Christ in history." It comes from the experience of "the power of the crucified, risen and glorified Christ, through the Holy Spirit and by faith."

In Schaeffer´s view what differentiates Christianity from any other religion, is that "God did everything". Schaeffer believed that "we can do nothing to save ourselves, because Christ has done it all."

Although he began by talking about cultural and emotional issues, using examples from art and philosophy, he always brought out mankind´s moral guilt, so to announce that Christ died for us on the cross.

Schaeffer saw himself as an evangelist. He never intended to be anything else. The key question for him was not what are Christian values about so that they may be considered worth believing in, but whether Christianity itself is the truth. It was not an intellectual question, it was more about the essence of life itself. If Christianity is true it affects our whole life. It is "the true truth“as he used to say.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The honesty and crisis of Francis Schaeffer