Schaeffer and the final apologetics

In search of authenticity (3): Francis Schaeffer’s interest was not so much to win arguments, but to win people.

30 AUGUST 2017 · 11:59 CET

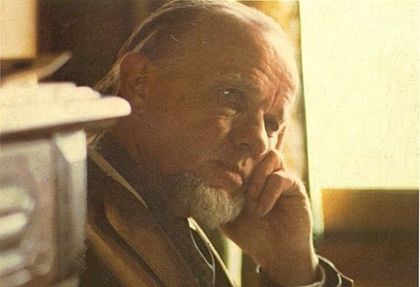

“Love is the final apologetic”, said Schaeffer. For that reason he shunned public debates. His interest was not so much to win arguments, but to win people.

“When he was talking to you, he was totally focused on what you were saying”, recalls Dorothy Woodson, “he was interested in you as a person. He didn’t care if you were the most unlearned or the most intellectual person in the world”. He cared only about the individual. For him, people were the most important.

In contrast to current apologetics debates which are quite a spectacle, or in contrast to the battling attitudes of so many believers on social media, Schaeffer believed that one could not bear witness to the faith without caring for the person in front of you.

“I tried to give sincere answers to honest questions”, but he always sought out the motivation that prompted those questions. If he had to face the new atheists today, he would not only respond to their arguments, but he would be asking himself what had shaped someone like Dawkins. He was interested in the person.

Only once did Schaeffer agree to enter into a public debate. It was in Chicago with the most controversial religious leader of his time, the radical bishop of California, James Pike. Although educated a Catholic, Pike lost his faith, and became an Episcopalian minister. He was well-known in the 1960s for his denial of fundamental Christian doctrines which he presented in a book for which he was not ashamed to be called “a heretic”. Pike not only defended civil rights with Martin Luther King and campaigned for the ordination of women in the church, but he attacked Catholic bishops for their opposition to abortion and accepted the homosexuality of his son, with whom he even tried to get in touch after his suicide, through Spiritism.

Schaeffer, however, showed him great kindness and many Christians did not understand why he was not more aggressive with him. The debate did not become well-known because of Fran’s attitude, but also because the bishop said things he had never said before, such as his famous phrase that had he hoped to receive the bread of life from the Church but that all they gave him were stones. He was very taken by Schaeffer's humanity saying he had never met anyone like him. No wonder they began a relationship that lasted until the mysterious death of Pike, who disappeared in the desert of Israel in 1969. Fran did not want to win arguments, he wanted to win people.

THE APOLOGETICS DEBATE

It is no easy task to fit Schaeffer into a particular school of apologetics. Protestantism has been divided since the last century into two schools that are still struggling to gain the attention of the Christian world.

On the one hand we have the evidentialism that is based on the traditional arguments for the existence of God. It is considered ‘classical apologetics’, although evangelicals have added to that basis in “natural theology”, their particular defence of the reliability of Scripture and the resurrection of Christ.

On the other hand, there is presuppositionalism in which Schaeffer was educated with Van Til in Westminster. This teaches that there is no neutral ground between the Christian and the non-Christian, because they start from different worldviews.

Some think that Schaeffer’s faith crisis is evidenced by the sequence of his written works such as his early books, which deal with apologetics - the trilogy that begins in 1968 with “The God Who Is There” and “Escape From Reason”, but continues with “He Is There And He Is Not Silent” (1972), but this is simply not true.

As we said in the previous article, it is “True Spirituality” (1971) which shows how he came through that spiritual crisis. In fact, the basis of his first book is already in note form in 1948. That year he published a review to the commentary by Oliver Buswell, an evidentialist theologian of his own denomination, who wrote about an introduction to the apologetics of Carnell.

Carnell became professor of the Fuller Seminary in 1948, after collaborating with Carl Henry, who was a presuppositionalist as was his teacher at Wheaton University, Gordon Clark. Like Schaeffer, Carnell had studied at Westminster with Van Til, before graduating from Harvard. He was one of the main figures with Ockenga, Henry and Ladd, some of the so-called “new evangelical” movement that would popularize Billy Graham, but he had nervous problems. He underwent psychiatric treatment and died mysteriously. He had accepted an invitation to speak at an ecumenical workshop organized by Catholics at a San Francisco Bay hotel in 1967, but when he did not turn up for the conference, a curate went up to his room and discovered that he had died from a pill overdose – it is not known whether by accident or suicide. He was 47 years old.

It is found in the inconsistency of the fact that the atheist does not commit suicide, even though he sees life as totally irrational. The author of “Escape From Reason” believes that this is a result of common grace, a very important doctrine, but hardly mentioned in evangelical circles although it has enormous implications in practical life. Although non-believers are not saved, they still live by the grace of God (Acts 17:25), who gives the gifts and talents to all, and this explains why Christians are not always the best politicians, artists or professionals.

What interests Schaeffer is not so much the question of conscience, which is a vital issue to “natural theology”, but more what he calls “the point of tension”. He sees his task as “rolling the roof back” for the “unbeliever”, so that he can see the inconsistency of his position. Here Schaeffer had a flexible approach. This varied from one person to another. He saw that presuppositions were contradictory, but he looked for a common life experience in them. Faced with evidentialism, he insisted that there is “common rather than neutral” ground, but he sees room for dialogue, as opposed to the presuppositionalist.

This is why Schaeffer is sometimes called an “inconsistent or compassionate presuppositionalist”, and “a thinking evidentialist”, since he seeks “to prove” presuppositions as hypotheses by their argument and their experience. It is a perspective similar to that of Keller in “The Reason For God”, as opposed, for example, to the evidentialism of McDowell.

THE GOD THAT IS THERE

The problem is that Schaeffer’s apologetic work is hardly known in Hispanic circles despite Jose Grau’s efforts. This is partly because his first book, “The God That Is There”, was never published in Spanish. It appears several times announced in titles and lists of Grau’s publishing house, ‘European Evangelical Editions’, but he never managed to get the book marketed, since the two translations that he commissioned were gibberish. He told me that the two texts that were presented to him were practically illegible. That is why the book that has most impact in our language - already in its third edition - is “Escape From Reason”, his peculiar History of thought.

The singularity of his work is not the intellectual demonstration of “The God Who Is There”, but his own personal experience, which is what “True Spirituality” speaks about. This was also true in the way L’Abri was financed. Faithful to the tradition of his in-laws, who came from Hudson Taylor’s Chinese “Faith Mission”, Fran only made known L’Abri´s economic needs in prayer to God. L’Abri never asked for money, but believed that “God would put in the minds of the people He chose the way they should share in His work”. That’s why they did no advertising nor did they even have brochures to start with. “God would bring the people he wanted and keep the others away”. There were no plans, no committee meetings.

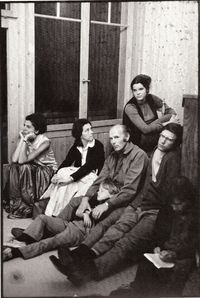

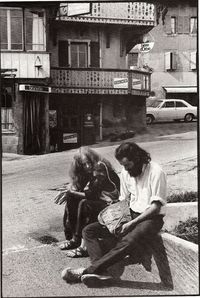

Time magazine published an article in 1960 saying: “every weekend the Schaeffer’s are inundated by a crowd of university students - songwriters, writers, actors, singers, dancers and beatniks - who profess all kinds of faith and unbelief. They are existentialists and Catholics, Protestants, Jews and left-wing atheists”. L’Abri, which means “refuge” in French was truly that to all of them.

In conversations, Fran put himself in his listener’s shoes in order to communicate the fact that God does exist, as it is revealed in the Bible, and that He both infinite and personal. That we are sinners by His standards but that Jesus Christ has come in space, time and history, to carry our punishment to the cross. This is how Edith summed up their message. That is the truth that we must communicate in love, not just as a cold concept, but with true emotion, because “love meets people where they are”, said Schaeffer.

This is because “God so loved the world that He sent His Son not to condemn it, but that it might be saved by Him” (John 3:16-17).

Read the first and second article of this series on Francis Schaeffer.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Schaeffer and the final apologetics