The man without a face

Any information that we have today of the existence of Spanish sixteenth century reformers we owe to a faceless man, Luis de Usoz (1805–1865).

09 OCTOBER 2017 · 11:00 CET

History is full of faceless individuals. Contrary to modern society, which is saturated with images of ourselves – so much so that that is all that some people can find to share–, the past has left us with few faces, save for those in power. This is especially the case of the unorthodox members of society, who do not even figure in the official histories.

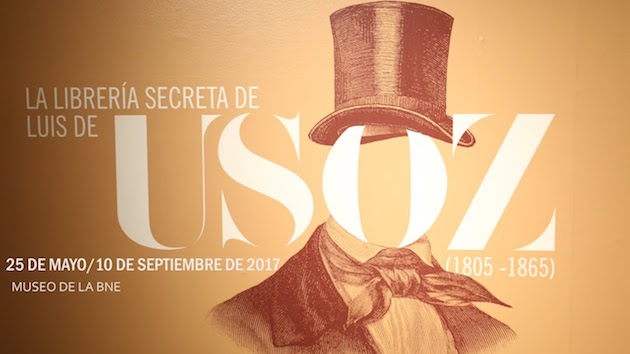

Any information that we have today of the existence of Spanish sixteenth century reformers we owe to a faceless man, Luis de Usoz (1805–1865), whose work was recently commemorated in an exhibition at the Spanish National Library in Madrid. The documentary director, Manuel Serrano Vélez, has also taken an interest in him as a result of a book that he wrote on Menéndez Pelayo, the historian of unorthodoxy in Spain. His book is entitled “Luis de Usoz, the discreet heterodox” (Luis de Usoz, el discreto heterodoxo).

This is not the first publication on Usoz, but it is the only one that has been made available to the wider public. In 1986 the untiring Irma Fliedner (grand-daughter of Friedrich Fliedner, a German missionary to Spain in the nineteenth century) published an anthology together with an extensive and documented introduction by Eugenio Cobo, a flamenco expert who took an interest in Usoz. Before that, a Quaker – the religious movement with which Usoz most identified – by the name of Domingo Ricart, decided to salvage his memory in 1973 with a first biographical attempt in which he accused the Spanish National Library of trying to sweep Usoz’s collection –donated by his widow in 1873 – under the carpet.

BOLIVIAN BORN

Son of a Spanish magistrate in the viceroyship of Peru, Usoz was born in 1805 in the modern-day city of Sucre (Bolivia), the capital of the province of Chuquisaca. His mother was well educated and translated books from French, but she died when he was only eight. He was brought up by his father until the age of 15, when he became an orphan. Usoz’s liberal conscience is largely due to his father, who was opposed to slavery and sided with the indigenous peoples of Peru, becoming involved in one of the first revolutions for independence. Having been banished, he spent some time wandering through the Peruvian highlands, before returning to Spain in 1816.

“In 1820, I met father Villaseñor, an erudite and persecuted Trinitarian friar who, when the Constitution fell, was by chance found in the street by the royalist mob, who were shouting and beating people. On seeing a friar they assumed that he was on their side and they embraced him saying: Father, long live religion! Villaseñor answered: Yes, my sons, but the religion of Jesus Christ, not yours”.

ROME AND THE BIBLE

That same year, Usoz studied Hebrew at the Institute of San Isidro, with the most important Spanish specialist in Semitic languages in the nineteenth century, Francisco Pascual Orchell y Ferrer. In addition, Luis had the great Hebraist Antonio García Blanco as a classmate. He also studied Morals and Natural Law in Madrid and in the nearby university of Alcalá de Henares. According to a letter from his younger brother, we know that he fought in a duel at around this time.

On receiving his bachelor’s degree, Usoz began to teach Hebrew in Valladolid, where he had already studied Law, after which he continued his studies in Bologna. He travelled through Italy, and following four visits to the Vatican, wrote, “I have clearly seen the poisonous fruits of the tree of idolatry”.

On his return to Madrid, he began writing in literary reviews and in the El Español newspaper, which was the most prestigious newspaper at that time, despite its liberal ideology, as one of the more moderate and least propagandist newspapers. He was then living in the Barrio de las Letras, the literary district of Madrid, where he participated in reviving the old Ateneo, a private cultural institution, teaching Hebrew alongside his friend Estébanez, an Arabic professor. A cooling in their friendship is reflected in a letter that Estébanez wrote to another friend in the summer of 1942, while Luis was in San Sebastián:

“Luis has become a first class heretic. He has republished a letter by Garcilaso in which he talks about the intrigues of Rome. His aim is to overthrow Catholicism. When I poked fun at his Puritanism, after he republished a satirical song book – known for its erotic content –, he went red in the face, but after he had recovered from his surprise, he replied with delightful cheek that he had republished the book to let it be known what kind of education the friars had given this country.”

QUAKER INFLUENCE

Around 1836, Usoz came into the possession of “An Apology for the True Christian Divinity” by Robert Barclay who, though not the founder of the Quaker movement – the founder was George Fox in the mid seventeenth century –, developed its theology a quarter of a century later, as tends to happen in many religious traditions –Luther is not the creator of Lutheranism, nor Calvin of Calvinism, nor Wesley of Methodism, nor Russell of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, nor Smith of Mormonism–. That same year, Usoz published a Spanish biography of William Penn, the Pennsylvanian founder of the Quaker movement.

The Quakers are a traditionally pacifist church, together with the Mennonites and certain branches of the Brethren. They give great importance to community life and simplicity, even in their services, which are almost always silent. They had a great influence in the American colonies, as well as in the fight against slavery, one of the aspects highlighted in the exhibition on Usoz, and which was also one of the characteristics of the first Spanish Protestants, such as Julio Vizcarrondo.

SECRET LIBRARY

Although there are no portraits of Usoz, a portrait of his wife does exists, painted by none other than José de Madrazo, the painter of Madrid’s high society. In 1837, Luis married a rich widow called María Sandalia del Acebal, freeing him from any material concerns and supplying him with resources, which he used generously. They lived together in Madrid’s literary quarter and it was thanks to his wife’s wealth that Usoz was able to publish so much.

His first publication was his 1837 edition of the New Testament, which he worked on with George Borrow, the first agent of the Bible Society in Spain. The translation was by Father Scio, with the notes left out. Usoz used the printing press of his own newspaper, El Español. As a result, the Bible Society was able to establish an office in Madrid, with Usoz as secretary. However, a Royal Order of 1838, issued by Governor Gamboa, led to the confiscation and banning of all its literature. Borrow ended up in prison, although he was freed eleven days later, as a result of diplomatic pressure.

Usoz became very careful with everything that he published from then on. His books did not use an imprint and his name and address were absent. The collection on Spanish Reformers was born out of a friendship with the Quaker, Benjamin Wiffen, who he met through Borrow. In 1840, Usoz travelled with Borrow to London, where he was introduced to Josiah Forster, a Quaker. He also tried to contact the English translator of the Spanish poet Garcilaso de la Vega, who he had heard was also a Quaker. The translator was Wiffen’s father, who had however died in 1836.

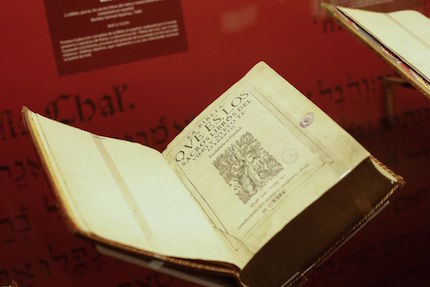

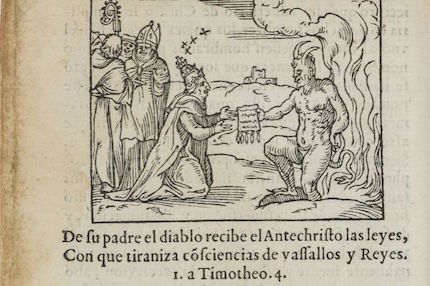

In London, he not only met Wiffen but also Calderón, a Hellenist and Cervantes expert who converted to the Anglican Church while in exile from Spain due to his liberal leanings. The latter was responsible for the publication of the first protestant journals in Spain, El Catolicismo Neto (The Distinct Catholicism – 1851–54) and El Examen Libre (The Free Examination – 1851–54). The collaboration of Usoz with Wiffen gave way to twenty volumes on Spanish Reformers, which they worked on clandestinely from 1843–47. The first volume was the so-called Carrascón by Francisco de Tejada. There followed the work of Juan Pérez, Juan de Valdés, Las Artes de la Inquisición (The Arts of the Inquisition), Valera’s treaties and his translation of the Institutes of Christian Religion by Calvin, together with the texts of Enzinas and Ponce de la Fuente.

BELIEVER IN JESUS CHRIST

The exhibition at the Spanish National Library did not only display copies of these books, as well as videos and prints, but it also included many of Usoz’s notes. One of the panels quoted correspondence with Manuel Matamoros, who had been imprisoned in Granada for his activities as an evangelist. When the latter asked him whether he was a Protestant, Usoz replied that he was not, being rather a “believer in Jesus Christ” whom he considered to be his Lord and Master. His answer did not seem to satisfy Matamoros, who insisted, eliciting the following explanation from Usoz:

“I wrote saying that I was not, nor wanted to be, a Protestant. This bold statement seems opaque to you, who might infer that I am nothing more than a papist believer. However, although I do not want to be a Protestant, I cannot and am not a papist or a Roman Catholic, nor do I want to be one, because I want to be a Christian. May this answer, in a letter, suffice”.

Usoz’s reticence to declare himself a Protestant is easy to understand. Matamoros was in prison and despite foreign pressure there was nothing to indicate that he was going to be freed. To call oneself a Protestant at that time was to risk going to prison. Furthermore, Usoz had observed the policies of some of the foreign missions that prepared to enter Spain from Gibraltar and considered their methods and interests to be far from evangelical:

“I am far from thinking that Christianity can be introduced into a country by means of packets of books and human liturgies, or through propaganda, or by reverend Protestant pastors attacking reverend Roman Catholic priests. In my mind, this all becomes a show, when its impulse is interest rather than love. As God is the only judge of this, I do not go so far as to roundly condemn this work and these efforts by others, but I do not trust them.”

The Christianity in which Usoz believed, was fed by the Bible itself. It was around this book that he would gather people at his house, saying a prayer that expressed true evangelical faith: “Bless, oh Lord, all meeting of Christians, and grant to those of us who here pray the understanding of your power and goodness, in the name of our only Mediator and Saviour, and the great and single sacrifice, for us once and forever, by our only Priest and Pontiff, Jesus Christ”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - The man without a face