Kurt Cobain: the weight of life

The documentary “Montage of Heck” demystifies him as a figure, showing his more intimate and solitary side.

19 MAY 2015 · 11:03 CET

Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) became a legend the day on which he pulled a shotgun to his head. His corps, found by an electrician, signed the epitaph of the “grunge” generation – who saw him as their “John Lennon”, according to Rolling Stone magazine–.

The documentary “Montage of Heck” demystifies him as a figure, showing his more intimate and solitary side. It looks at his difficult childhood, his continuous stomach-aches and his tempestuous love story with Courtney Love. His fragile personality and depressive character ended up making life unbearable for him. Nirvana’s story ended up being incredibly short. Despite being so short, it provided a striking illustration of the “vanity of vanities”, described in Ecclesiastes. Cobain, like the Preacher, discovered that in this life all is vanity…

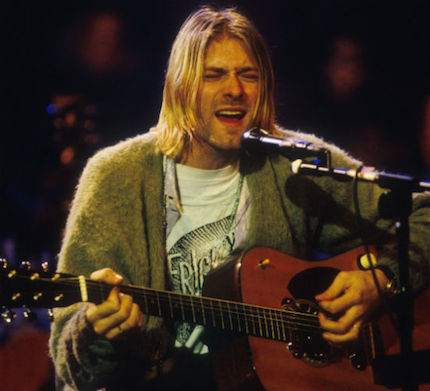

When “Nevermind” was released in 1991, there was nothing to suggest the success that Nirvana would achieve (although the offer to sign with Geffen, after having recorded with an independent company like Sub Pop, shows that someone must have had some foresight). There were only thirty-one months between the launch of this album and the end of his career. Nirvana only had two official albums to add to their previous album, Sub Pop (Bleach), and a compilation of unedited songs. Posthumously, a television-recorded acoustic concert appeared as part of the famous series Unplugged, live “from the muddy banks of the Wishkah”. In no time, they had become the most famous band on the planet.

The band combined a punk attitude and heavy metal guitar creating legendary pop tunes, crowned by Cobain’s grungy growling. It was powerful and distressing. For adolescents in the 1990s, Nirvana was the perfect soundtrack for the final apocalypse of a millennium that had seen the breakdown of a generation whose children went from one parent to another, without the security of being accepted by either of them.

With the burden of this feeling of pain and abandonment, the guitar riff in “Smells Like Teen Spirit” provoked an emotional catharsis, which turned Cobain into the mouthpiece of a whole generation. The so-called Generation X, instead of giving a literary expression to their alienation, found in this era of visual bombardment a musical explanation which served as its collective confession of faith in its quest for exorcism. It provided consolation for childhoods broken by the destruction of the family.

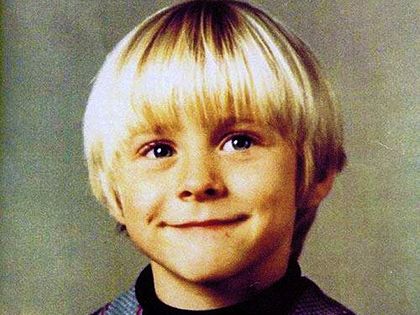

BROKEN CHILDHOOD

Cobain seems to have been a normal child until his parents’ separation. He was born in a sleepy town in Washington State, but he became known when living in Seattle, the 1990s’ capital of pop. It was there that he died. He already suffered from stomach problems, but the breakup of his family “just destroyed his life”, according to his mother.

In his suicide note, Cobain wrote: “since the age of seven, I've become hateful towards all humans in general”. He thus let himself slide down a slippery slope which led him to a “world of heroin abuse, acute paranoia, wilful self-destruction, shoulder shrugging nihilism, and child-like love”, as Phil Sutcliffe described him in an interview with Q magazine, in an article entitled “Kind of Pain”, published six months before his death.

“My body is damaged from music in two ways”, Cobain said to Jon Savage: “they find a red irritation in my stomach. But it’s psychosomatic, it’s all from anger. And screaming…[and] I have scoliosis […] the weight of my guitar has made my back grow in this curvature”. And so the lead singer of Nirvana said that he was in “pain all the time. Then add the pain of our music”. The pains in his stomach could have come from medication that he had taken since he was little, Ritolin, used to manage his hyperactive behaviour. What is certain is that heroin was a fatal addiction in this emotional cocktail, which reached breaking point when he was twenty-seven years old.

His diaries, which were published eight years after his death, speak of his struggle with the addiction. In a note written on the stationery of a hotel in Madrid, only a few weeks before his suicide, he said that at first he laughed at the idea that someone could become addicted after their first try: “I now believe this to be very true”…

His life is a sad and despairing story which was captured in that photograph by Ian Tilton for the now disappeared British music newspaper Sounds. In it we see him sitting on the floor, with one hand on his temple with an expression of pain. This image was chosen by Q Magazine as one of the hundred best photographs of the history of rock. Tilton says that he took it during a tour in Seattle, before they became famous: “He was aware I was there, but it didn’t bother him that I took the photograph. The band also accepted him crying, so it was probably something that he had done before”.

A SEA OF CONTRADICTIONS

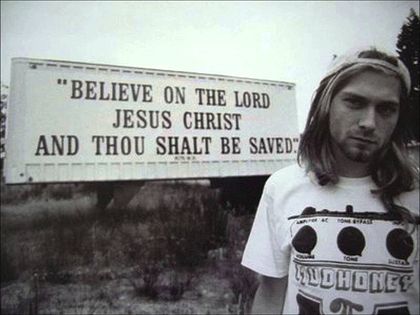

In his biography “Heavier Than Heaven” Charles Cross says that the reasons for his death could have been: (1) the despair of his addiction; (2) his constant stomach pains; (3) his emotional suffering; and (4) the hallucinogenic effects of the combination of drugs that he was taking. But it is also very interesting that he adds that in the end it was a spiritual issue. In the introduction to his book, he also talks about his “questions concerning spirituality”.

Fame of course did nothing for his spiritual wellbeing. It moreover exacerbated his problems. It gave him money for drugs and accentuated his contradictions. In his video, “Live Tonight Sold Out”, Cobain made it clear that he did not like huge concerts. Success does not seem to be was he was looking for, since his group played more to the underground culture. His vocation was clearly marginal, but they became the most famous band on the planet. Cobain’s fragility, however, made it difficult to survive that meteoric rise. His song “Very Ape”, is a clear confession of how he feels “buried” in his lies and contradictions.

Another of his biographers, Christopher Sandford, is more cynical about his aversion to fame. In his opinion: “His whole approach to performance was a scream for attention”. What is clear to him is that “What Cobain never knew was contentment”. Which takes us back again to Ecclesiastes. Being famous isn’t the solution to our problems: “No one remembers the former generations, and even those yet to com will not be remembered by those who follow them.” (Ecc. 1:11). The music chart number ones are prime evidence of the fate of Andy Warhol’s “fifteen minutes of fame”.

ALL IS VANITY

Ecclesiastes is the first album of conceptual rock ever written. It would have been a magnificent subject for a Nirvana album. Much of it has been rewritten once and again in the fifty years of rock history. In a conceptual album a song cannot be taken out of context. This is also true of Ecclesiastes which has to be read in its entirety in order to reach its conclusion, which is something that Cobain didn’t do, even through, like its author, he set out to find a meaning in his life. The Preacher sought that meaning in pleasures, education, good works and all kinds of wealth, to finally reach the conclusion that all is vanity (Ecc. 1:2).

As on a rainy day, the rain falls on the rivers which flow into the sea. Then the water rises back up to the clouds, to fall as rain on the rivers which flow into the sea, to then return again to the clouds. That is the tedium and repetitiveness of everything, according to the preacher. “All things are wearisome, more than one can say.” (v.8) There is nothing new under the sun. So, what is the point of continuing with the cycle? Douglas Coupland wrote a modern version of the book he published in 1994, “Life After God” : “Is feeling nothing the inevitable result of believing in nothing? And then I got to feeling frightened - thinking that there might not actually be anything to believe in, in particular”.

At the end of the book Coupland makes a surprising confession: “Now, here is my secret: I tell it to you with the openness of heart that I doubt I shall ever achieve again, so I pray that you are in a quiet room as you hear these words. My secret is that I need God.” It sounds something like Ecclesiastes. Maybe there is really nothing new under the sun. Everything we do seems to be futile, but maybe we need to look up…

BEYOND THE SUN

It is only when we see ourselves from the other side of the sun, from God’s perspective, that we can find a meaning in this thing called life. The author of Ecclesiastes concludes at the end of chapter 12 by saying that the secret lies in God. There is a vertical dimension, in addition to the horizontal dimension. Paul speaks of these two dimensions in his second letter to the Corinthians. Through them we “fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen”, and we discover that “what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal.” (4:18). That is why Jesus said: ““Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth” (Matt. 6:19-20).

It is easy to imprison our lives between the walls of our time and perspective. We confine ourselves to our circumstances and the limitations of what we can see and hear and we lose hope and cannot see a way out. U2’s Bono describes it as being “stuck in a moment you can’t get out of”. They wrote that song for a friend of theirs – a singer called Michael Hutchence – who, like Kurt Cobain, also took his own life.

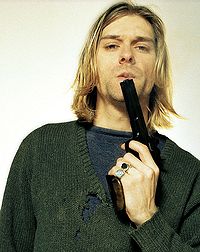

He is making a declaration, not a prophecy, in the picture of him with a gun in his mouth, or in the home video that he shot age 15, known as “Kurt’s Bloody Suicide”. His pain thus becomes the icon of a whole generation, which sympathises with his despair, weakness, confusion and lack of purpose.

That is why Jesus came down to Earth: to sympathise with our pain and weakness, suffering in our stead, when he bore our guilt on the cross. Just one year after Cobain’s death, four of his fans when from Toronto to Seattle to pay tribute to their hero by hanging themselves. The next year, that Friday was Good Friday…He who can empathize with our weaknesses (Heb. 4:15), suffered the death that we deserved, taking all our guilt and misery. His death was not a useless sacrifice, like Cobain’s, but an act of rescue, through which he gave us life. Through his resurrection he has also given us eternal hope, breaking the futile cycle of this life under the sun. So, let us look up!

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Kurt Cobain: the weight of life