Azaña and the Bible in Spain

The life of George Borrow and his passion for bringing the Bible to Spain fascinated the politician and republican president Manuel Azaña.

26 JUNE 2015 · 10:15 CET

The Spanish publishing house, Trifolium, has retrieved from the Mexican edition of the Complete Works of the republican politician Manuel Azaña, his study on “George Borrow and the Bible in Spain”. This famous nineteenth century travel journal recounts the exciting story of “the Journeys, Adventures, and Imprisonments of an Englishman in an Attempt to Circulate the Scriptures in the Peninsula”.

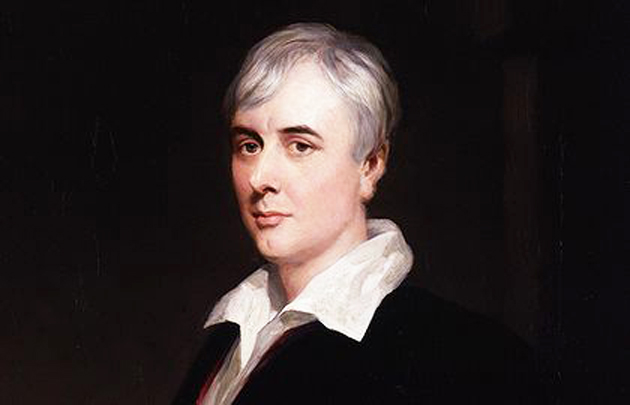

Borrow was an eccentric who became known in Madrid as 'Don Jorgito el Inglés' (Don Georgie, the Englishman). This quixotic traveller traversed Spain in the midst of the Carlist Wars, in the company of his most cherished book, the Bible. Following his conversion from atheism, he had travelled with it to Russia, on the basis of a faith which led him to become an agent for the Protestant Bible Society in Catholic Spain.

The story of his adventures in English was published in three tomes in 1842. In less than a year he had run through seven editions selling some twenty thousand copies. His book was translated into German, French and Russian, but it did not reach Spain until 1921. His memoires were first translated into Spanish by the man who would go on to become the president of Spain’s second republic, Manuel Azaña.

RECOVERED EDITION

The book could not be republished until the 1970s. Azaña wrote an extensive and interesting prologue, which is reproduced by Trifolium. In addition to his Spanish translation–published by Alianza Editorial–, there is another translation by Elena García Ortiz from the 1950s. This was republished by Ediciones B, as part of its travel writing series, with a new prologue by Emilio Soler Pascual.

Pope Pius IX even went so far as to prohibit the circulation of the Bible without commentary in 1864. He also denounced communist activities and Bible Societies. For Borrow, however, this was the Word that gave him new life.

BORROW THE ECCENTRIC

Azaña describes Borrow as a melancholy child, fascinated by gypsies. His father was a captain in the Napoleonic wars. A friend of his had recommended law as the best career for someone who wasn’t looking for one and, in that line of business, he lived in Norwich, as an atheist, sentimentalist and prodigious polyglot, until he decided, at the death of his father, to move to London and begin life as a translator.

Borrow went through a dramatic conversion following a period of deep depression. From then on, according to Azaña, Borrow’s Protestant faith was just as fanatic as the atheism that he had abandoned. He got the Bible Society to send him to Russia to publish the New Testament in the language of Manchuria.

He had just returned and was planning to travel to China when Don Jorgito undertook the risky mission of trying to publish the Bible in Spain without annotations. He managed it, but not without a passage through prison. The edition that he published in Madrid was confiscated.

SOAP TO WASH SOULS CLEAN

The book that tells this story was published in London in 1842. Six editions were exhausted that same year in England, and two in the United States. A well-travelled Spanish author, Julio Llamazares, believes that Borrow is the English writer who acquired the widest and most thorough knowledge of the highways and byways of Spain during the nineteenth century.

Don Jorgito was more than just a traveller. He had a mission to accomplish. That is why he appeared amazed to see that a “large edition of the New Testament had been almost entirely disposed of in the very centre of Spain, in spite of the opposition and the furious cry of the sanguinary priesthood and the edicts of a deceitful government”.

Borrow thus believed that “a spirit of religious inquiry [had been] excited, which I had fervent hope would sooner or later lead to blessed and most important results”. These words were left out of Azaña’s translation and have still not been fulfilled today …

As that woman who stopped Borrow along his way to ask “Uncle (Tio), what is that you have got on your borrico (donkey)? Is it soap?”. We should, like him, still reply, “Yes, it is soap to wash souls clean”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Azaña and the Bible in Spain