What just happened to nuclear fusion? And what is it?

It is said that fusion is an endless and clean source of energy. That is true. What has been achieved in the US is very important, but it is still a long way to go before a commercial plant is built.

20 DECEMBER 2022 · 11:49 CET

Last Tuesday, 13 December, headline on front pages of newspapers such as El País in Spain read: “The US announces a 'historic scientific achievement' towards endless energy with nuclear fusion” [1].

Let's see what that means.

What is nuclear fusion?

An atom is a nucleus, made of protons and neutrons, with electrons dancing around. The nuclei of atoms can react with each other. They can either break into pieces, or join together, i.e. fuse.

Among all the phenomena that can occur between nuclei, only two types of reactions can provide energy:

- Cutting a fat nucleus into two. This is called fission. The bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 used this principle. The over 420 nuclear power plants that generate electricity all over the world also use this principle. The first one started producing electricity in 1954, only 9 years after the bombs.

- Fusing 2 small nuclei. That's called fusion. The so-called H-bomb uses this principle. The first test of an H-bomb took place in 1952. Today, 70 years later, there is still no nuclear power plant that generates electricity from fusion. Apparently, taming fusion is more difficult than taming fission. By the way, fusion is the energy source of the Sun and all other stars.

Why is fusion so difficult to tame?

The reader may remember the following: opposite charges attract and equal charges repel. Right. That is enough to understand why fissioning is easy while fusion is not.

Fissioning, cutting a fat nucleus into two, is easy: just send a neutron to it. As the neutron approaches the nucleus it is going to split, it sees the neutrons and protons in the nucleus.

Since the neutron is... neutral, the protons in the nucleus neither attract nor repel it. It goes on its quiet way until it hits the nucleus and splits it apart.

Now suppose I want to fuse two light nuclei. Two hydrogen nuclei, for example, each consisting of a single proton. As they approach each other to fuse, the protons see each other. Being of the same sign, as we were told at school, they repel each other.

It takes much prodding to bring them closer together. And when they are close enough to each other, another phenomenon arises that we were not told about at school [2]: they stick to each other [3]. The fusion is done. But it took some pushing.

Now, what does this need to “push” mean? If I have hydrogen atoms in front of me and I want them to fuse 2 to 2, in the real world, “pushing” means giving them enough energy to get them close enough to stick together.

In even more concrete terms, it means heating them up to about 100 million degrees. This is not a typo. I definitely wrote 100 million degrees. Obviously this is very difficult to control.

What just happened in the USA?

It takes a lot of energy to heat up to 100 million degrees. So if what I get out of my fusion reactions is less than what I spend to heat, it's not worth it. It's like investing 50 euros to get 30 euros in total.

What has just happened in the USA is that, for the first time in 70 years, more energy has been obtained in a fusion experiment than the amount spent to produce it. 1.53 times more, to be accurate.

How long will it take to have a nuclear fusion plant?

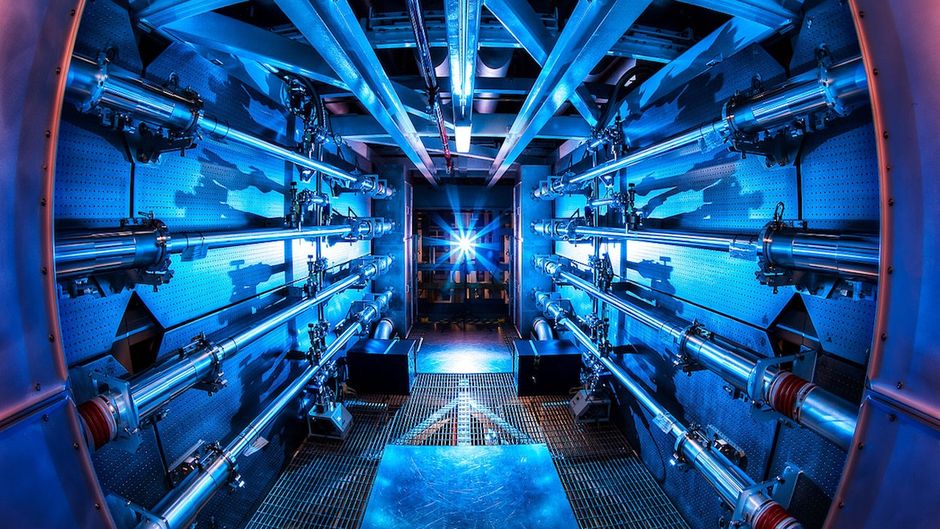

Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California used the energy of 192 giant lasers, which fill the surface of 2 football fields (I visited it in 2012), to heat a small hydrogen sphere of a few millimetres [4].

The experiment lasted about 10 nanoseconds, the time it takes for light to travel 3 metres. At the moment it can only be repeated once a day. And as mentioned above, the energy gain was 1.53.

A nuclear fusion plant generating electricity would have to repeat the same operation several times in a second instead of once a day, and each time reach an energy gain of about 100 instead of 1.53.

As Omar Hurricane, one of the programme managers, said in a scientific talk I attended in August 2021: “If this were a commercial airliner, we would be at the Wright Brothers' stage”.

What are the promises of fusion?

It is worth contrasting fission with fusion to understand why, despite its difficulties, so many people are investigating fusion.

I start with the common ground before going through the differences.

The common ground between fission and fusion:

- Neither relies on chemical combustion reactions, so that neither emits CO2.

- For very key reasons [5], both typically require 1 million times less material than fossil fuels to generate the same energy.

Differences between fission and fusion

- As we have seen, it is easy to fission, to cut a fat nucleus in two: just send a neutron into it. It is then possible to lose control of a fission plant (as happened in Chernobyl and Fukushima).

On the contrary, once you have fused a hydrogen ball with the 192 lasers, the next balls cannot come by themselves, nor can the lasers fire by themselves: by design, there is no loss of control possible in fusion.

- The fission of a fat nucleus produces radioactive waste. It is the result of the laws of nature, impossible to avoid.

With fusion, there is a choice. Depending on the fusion reaction chosen, no radioactivity is generated at all, or much, much less than in fission [6].

Conclusion

It is said that fusion is an endless and clean source of energy. That is true. There are nuances, but it is true.

However, what has just been achieved in the USA is very important, but there is still a long way to go before a commercial plant is built.

To limit global warming, CO2 emissions should be reduced to zero within 50 years [7].

Will fusion help? Unless there is a very good surprise[8], I doubt it. Even if we had a nuclear fusion plant in 20 years, it would take an incredible annual growth rate [9] for fusion to account for, say, 40% of the world's energy production in the remaining 30 years.

In the long term, however, fusion could be a very significant source of energy for the 22nd century and beyond.

But will humanity know how to handle it better than a teenager who would receive millions as a gift? That is another question.

Antoine Bret, Professor in Physics at the Castilla-La Mancha University (Spain).

Notes

[1] The report was published in the paper edition on Wednesday, 14.

[2] This is no conspiracy. If nuclear physics were taught at school, there would be no time to teach much more general and essential things, such as history, language, physical education, arts and crafts, etc.

[3] In scientific jargon it is said that the "strong nuclear force" overcomes the "Coulomb force" at very short distances.

[4] There is another way of researching fusion: the so-called "magnetic fusion". It recently achieved an energy yield of 0.33. The ITER project is following that path.

[5] Relative strength of the strong nuclear force and the Coulomb force.

[6] The current reaction under consideration is the fusion of deuterium and tritium. It produces helium, which is not radioactive at all, and a neutron, which can activate the material in the walls of the reaction chamber. There are other fusion reactions that do not even produce a neutron, such as the fusion of a proton with a boron nucleus. But the easiest to produce is deuterium-tritium. That's why we start with that one.

[7] See the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

[8] The surprise may come from the many private companies that have just invested in fusion.

[9] More than 34%.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Features - What just happened to nuclear fusion? And what is it?