Redeeming Politics?

Why is it that Christians generally feel more of a compulsion to use their democratic franchise than others? And can this inform those who have lost hope in our democracy?

24 MARCH 2015 · 18:50 CET

What would it be like to be awoken suddenly by your parents in the middle of a starry night, to roll yourself out of your bed, run down the close, and tumble into the Anderson Shelter for fear of the incendiary bombs that are falling from the sky?

What would it be like to drive a truck back and forth to the front line, constantly under fire, bringing back the dead and wounded from the battlefield slopes of Monte Cassino? How would that affect your view of the world? What would be your reaction to losing your best friend to the arbitrary trajectory of a high explosive shell? How do you think you would spend your life in the aftermath of these events?

Even in our turbulent times, it’s hard to imagine what my Grandparent’s and their peers had to endure during the Second World War. It’s also difficult to grasp how, after all they experienced, they managed to pick themselves up and throw themselves into building the peace, and to renewing a society which until that point had been grossly unequal. My Grandpa in particular found an outlet in the Union movement and in local politics to play his part in creating a new kind of society. If Union and Political Party membership is anything to go by, so did millions of others.

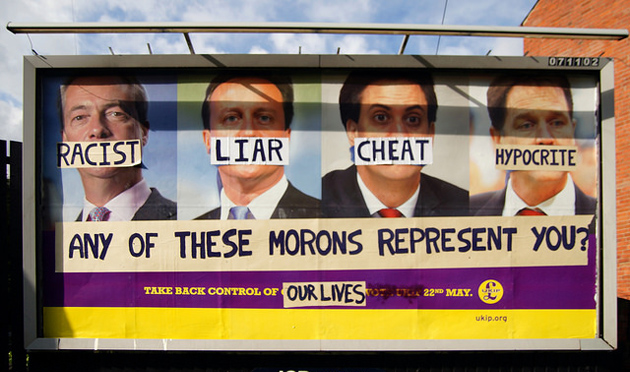

But by the early stage of the 21st Century this civic engagement – and in particular, engagement with politics – has become much more of a niche pursuit as apathy, disenfranchisement and disaffection with our political process has grown. Just ask any taxi driver the views of their customers on politics for a depressing insight into the rise of cynicism.

It’s become an almost-hackneyed idea to encourage voting by an appeal to the sacrifices of previous generations. For me, the stark contrast of how things could have been without the victory over Fascism secured by people like Bill and Cath, remains a powerful reason to not just vote but to get involved in our political process. But the truth is, it’s not really enough for many people today. Many feel that politics is something which happens to them, not through them, and have entirely given up, on the trip to their local polling station on Election Day, let alone any more active involvement in politics.

Although this spectrum of non-voters includes those of all Faiths or none, it’s interesting to note that, according to recent research, 8 in 10 Christians are likely to vote in the election; double that of the general population. With the first General Election in the UK in five years nearly upon us, one which is likely to be the closest and most unpredictable in a generation, why is it that Christians generally feel more of a compulsion to use their democratic franchise than others? And can this inform those who have lost hope in our democracy?

First though, a confession for the Register of Interests: I’m not only a Christian, I’m a Labour Party member and on the left of the political spectrum. Everything I say here comes from that perspective.

So, what kind of politics are we aiming for? Let’s assume we’re talking about democracy only. It’s what we’ve got, and as Churchill famously said, “democracy is the worst form of government except all the others that have been tried”. Simply put, democratic politics is the process through which society orders its priorities, and through which we express our understanding of Public Good.

This should be a concern for all people in society, and it’s certainly the concern of a Christian and Biblical worldview. Understanding and then creating Public Good is something that we can either participate in or not. But it’s never something which we can remove ourselves from. As Nick Spencer has said, “However much we might attempt to privatise life – whether through the adoption of human rights or the extension of market mechanisms into every aspect of life – shared public “space” is an irreducible phenomenon, and public space which is not simply anarchy must be governed by some idea of the public good”.

So why is Public Good so central to a Christian worldview, and how can this guide how we assess our politics, and even how we use our vote? I believe that the political party which most closely applies the following ideas in its policies and vision is both worthy of your vote and likely to form the best government.

Love of neighbour – we might as well take first things first. The injunction of Jesus to love your neighbour as yourself is the core idea at the heart of Christianity on how Christians should aim to live with other people. For the avoidance of doubt, the Parable of the Good Samaritan makes it abundantly clear that this means all people, including our enemies. If politics is the process through which society orders its priorities, loving your neighbour through politics means that we should shun individualism, selfishness and sectionalism in all areas of life, including in government.

The equal worth of all humans, before God – Part of the reason that we’ve to love our neighbours is because we’re all equally sinners (“All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God”) and because we all equally and beautifully reflect the image of God. In this sense, all humanity is equally precious and equally broken: no-one is inherently more valuable than another. Our political system and the Government it produces should reflect this in the way it views individuals, taking as a first principle the idea that all citizens have the same intrinsic worth – regardless of their social standing or background. But Governments should do more than recognise our inherent equality; they should actively work to reduce inequality. The Biblical understanding of human nature recognises both our tendency towards fallibility and the immense capacity within humanity for progress. If applied by governments, this understanding would lead to policies that encourage the goodness within humanity to rise to the surface and empower those who have been marginalised by the brokenness of our world.

God’s deep concern for Justice– Love and Justice are closely intertwined. As renowned Evangelist and theologian Tony Campolo has noted, “If we stop to think about it, justice is nothing more than love translated into social policies”. Although the death and resurrection of Christ on the cross is the best example, God’s heart for justice is a consistent theme throughout the Bible and indeed throughout human history. Reflecting our creator, at our best humans recognise and express justice in our relationships with one another as we act upon the Moral Law (as described by C.S. Lewis) which we find within ourselves. In this sense, justice is simply love manifested in our interpersonal and social relationships. This is equally true when we think of government. So, to reflect God’s desire for justice, the Politics that Christians support should be that characterised by justice: economic, social and criminal.

Righteous and Servant Leadership –Whereas the typical approach to politics in general and leadership in particular has centred around the control of power – most often of one group over others – the Biblical template for leadership is one of humility and service to others. This template for leadership and authority again stems from the idea that we are to put the needs of others before our own. In the New Testament we see the explicit teaching of Jesus about the revolutionary nature of the Kingdom of God where the first shall be last and the last first. Practiced in politics, this counter-cultural worldview would create a system of governance in which elected officials would truly be public servants. This therefore requires a leadership which doesn’t accrue power for its own sake, but for the sake of the society it serves. It also implies the need for a political process which is open, transparent and which provides checks and balances against our autocratic tendencies. Finally, righteousness (often called integrity) is a characteristic of a servant leader who doesn’t accrue power or wealth for themselves. If you are truly serving others, you are not seeing political leadership as an opportunity to benefit yourself or your clique.

No political party perfectly reflects these values in their ideology. And political leaders will always let us down. But it’s incumbent on each of us to make a judgement about the individuals and political party which we think most closely characterise them, and give them our support, if only to hold them to the standards that we expect.

I know I have. And so did Bill and Cath.

David Smith is Head of International Programme at the Bible Society (UK). Expert in Peacemaking programmes. He tweets at @1davidwsmith

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Features - Redeeming Politics?