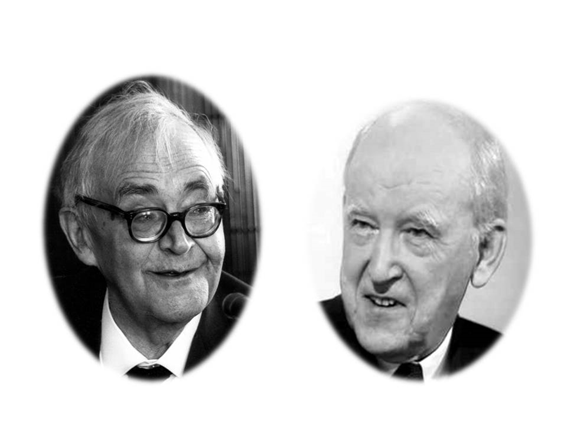

The differences between Lloyd-Jones and Barth

Seven theological differences between Martyn Lloyd-Jones and Karl Barth.

23 JULY 2016 · 08:05 CET

When the Swiss theologian Karl Barth died at 82 years old back in December 1968, the Welsh preacher Martyn Lloyd-Jones wrote an obituary for him in the Evangelical Times.

In spite of recognizing Barth’s greatness as a first-rate intellectual and praising his resilient fight against Hitler’s Nazi regime, Lloyd-Jones esteemed that Barth’s writings had done practically nothing for the cause of the Gospel.[1]

After this initial critique, the Westminster Chapel minister went on to offer seven more reasons why Barth never enjoyed much popularity amongst conservative Evangelicals.

1.- Barth accepted Higher Criticism

Lloyd-Jones attacked Barth for dedicating too much time and energy to the insights of Higher Criticism, that is, the historical critical method which was mainly interested in establishing who wrote the different chunks of the Bible and how the information was put together. According to Lloyd-Jones, such Higher Criticism turned Scripture into a run of the mill book and therefore denied its divine authority. Instead of flowing down the modern current, Lloyd-Jones took the Bible as the Word of God and as the sole source of Christian faith and conduct. He hit out at Barth because the Swiss thinker didn’t believe the Bible to be the Word of God in the literal sense of the term but in a metaphorical sense i.e. the Bible ‘contains’ the Word of God and ‘becomes’ the Word by means of an existential encounter with Christ.

As the Reformed Italian scholar Leonardo de Chirico put it: “Despite [Barth] having called attention to the Word of God, his theology of the Word has not actually prevented the long wave of theological liberalism, marked by severe skepticism towards the trustworthiness of the Bible, to become the framework of mainstream Protestantism”.[2]

2.- Barth denied propositional revelation

Propositional revelation, defended by both the Reformers and Lloyd-Jones, teaches that God wants to make Himself known to humanity through written propositions or truths. Therefore the recorded words in Scripture are literally God’s revelation to mankind. Barth, however, didn’t want to bind God to a simple linguistic formula thereby asserting that the words of Scripture are a kind of ‘propositional witness’ to the revelation of God. In other words, the revelation God gives through the Bible is always indirect.

3.- Barth distinguished between Historie and Geschichte

Lloyd-Jones criticized Barth for dividing history in two distinct blocks, namely, the sacred and the secular. Rather than remaining faithful to the Reformed tradition which confessed that God revealed Himself through literal historical events, Barth pointed out that the only revelation of God came about in and through the transcendental Christ-event, which can never be controlled by history. Barth received this teaching regarding Historie (real, objective history) on the one hand and Geschichte (subjective, existential history) on the other hand from his liberal theological professors whilst at university.

4.- Barth’s teaching didn’t stream down to the masses

Another criticism Lloyd-Jones levels against Barth is that his theology didn’t produce any kind of revival throughout the twentieth century. “Though his works and influence have been in existence for 50 years, he has brought no revival to the church”. In this mode of thought, the Welsh preacher denied that Barth could be considered as a true Protestant giant alongside the likes of Luther and Calvin as they were a lot more than mere academics. They were used to revive and reform the church of the Lord in a powerful manner in their generation.

5.- Barth was more of a philosopher than a preacher

In the final analysis, Lloyd-Jones explained that Barth’s thinking couldn’t have produced any real revival because his style was too philosophical. He argued that Barth, “in spite of his denials, is essentially philosophical”. Barth didn’t exactly aspire to the simplicity that is to characterize a Gospel minister and therefore his books are oftentimes hard to understand. A preacher –as Lloyd-Jones believed- had to combine depth with straightforwardness. Barth fell into the trap of bending and twisting Scripture into his pre-conceived philosophical scheme.

6.- Barth’s disciples didn’t preach the Word

With regards to Barth’s disciples, Lloyd-Jones lodged a complaint that they spent too much time preaching “about” the Word rather than getting down to the nitty-gritty of actually preaching the Word. For the most part they were intellectual preachers who didn’t touch the hearts of their hearers throughout Scriptural application. This sad reality, in one way or another, had something to do with Barth’s philosophical methodology.

7.- Barth was an ecumenical

Lloyd-Jones guessed that Barth’s theology would end up forging a bridge between Protestantism and Catholicism, or more precisely, between “a modified (but not truly reformed) Roman Catholicism and a degenerate Protestantism”. The Welsh minister commented that many liberal Catholics were studying Barth’s writings with some enthusiasm and wanted to reread the Council of Trent in a Protestant direction. Given Barth’s own growing ecumenical concern and his presence at the Second Vatican Council, it’s not at all surprising that Lloyd-Jones would have harboured such thoughts.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Fresh Breeze - The differences between Lloyd-Jones and Barth