The cumulative crisis of trust

Our churches should be examples of institutions that serve the common good, that speak out against injustice, and that are led with integrity.

24 FEBRUARY 2017 · 11:02 CET

To what extent do the political upheavals of 2016 reflect a crisis of trust in public leadership? Although politicians have long been regarded with a healthy degree of scepticism, a more insidious loss of credibility in public leaders has been growing over the course of this century.

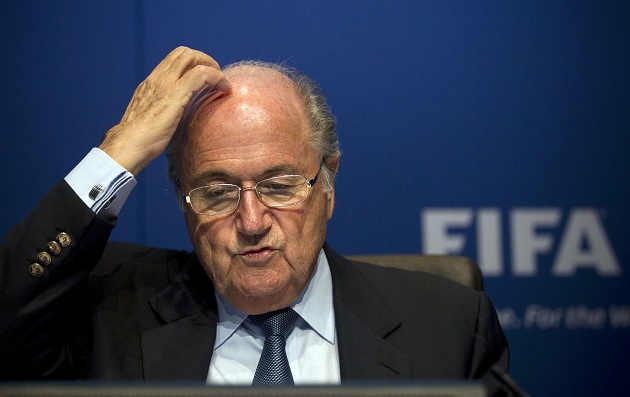

First the sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church, then the banking crisis and scandal around executive pay and bonuses, the outrage around MPs expenses in the UK, followed by newspaper phone-hacking, then doping in sports at the highest level. Between them came relentless sex abuse scandals involving politicians, media celebrities and most recently football coaches.

The popular conclusion is that people in positions of power can no longer be trusted. When a growing disillusionment with established leaders is combined with the powerlessness felt by those who are on the losing side of globalisation, then people may rally around populist demands for change in sufficient numbers to tip the balance of power – hence Brexit and Trump’s victory.

Yet behind these political and economic challenges lies a moral one. The Bible gives clear warnings about the personal temptations surrounding power and the dangers of overcentralized authority. It envisages two factors to keep this in check: inner restraint and outer controls. The first and more important is built on moral character that includes integrity, impartiality, and trustworthiness; Jesus sums these up in the idea of servant leadership (Luke 22:25-26). External controls – taking legal or institutional forms – are designed to reinforce inner restraint, but not replace it.

Consider the motto of the London Stock Exchange: dictum meum pactum – ‘My word is my bond’. This is a far cry from the modern culture of business, where according to Jon Huntsman, corporate lawyers ‘…have created, perhaps unwittingly, a tidal wave of distrust, ended long-term friendships, and bartered the inherent goodwill between people for loopholes, escape clauses and weasel wording.’[1] The gold standard of personal integrity has given way to weaker (and more costly) legal restraints to ensure honesty and fairness in contracts.

When it comes to politics, I can remember the first time that a British cabinet minister, having been exposed for an affair, didn’t resign, nor was he sacked (in the late ‘90s). Prior to that, the consensus was if a government minister was found to have broken his promise to his wife, how could he be trusted to keep promises to the electorate? Not so today; MPs have to be caught doing something much more sordid to resign now. All this diminishes their reputation as being worthy of public trust.

The shocks of Brexit, the Trump victory, and the Italian referendum are evidence that public trust has run out towards the people who hold the political and economic reins. And it’s probably not over yet, as the march of populism is swelling in several European nations.

Five hundred years ago, Martin Luther also faced a crisis of trust in public leadership – in the medieval Catholic Church, which exercised considerable political and economic power as well as spiritual authority. His 95 theses were objections to corruption, and over time the Reformation led to a transformation of the culture of leadership.

One of the key ideas of the Reformation was that every person must give account to God for their lives directly, and that faith in Christ not the intermediation of the Church would determine the outcome. This helped forge the moral outlook which led to the inner restraint mentioned above.

Another outworking of the Reformation was the belief in the unique worth of every human being – on account of being loved by God and saved by Christ. This underpinned the emergence of the rule of law – which limited the autocratic power of kings and rulers, and upheld the rights and dignity of every human being. From this developed the institutional separation of powers, those external restraints designed to limit the power of any one person or office.

Is there anything we can learn from the Reformation as we face a widespread loss of trust in public leadership in 2017? How can the Church today help restore the vital civic virtues of inner restraint and the integrity of institutions?

Jesus gave us the mandate to be salt and light in our culture, so it surely begins with each one of us being trustworthy within our own sphere of influence at home and work. If we are faithful and trustworthy in small matters, said Jesus, we will be the same in large ones (Luke 16:10).

Likewise our churches should be examples of institutions that serve the common good, that speak out against injustice, and that are led with integrity.

Jonathan Tame, Director of the Jubilee Centre (Cambridge, UK).

This article first appeared on the Jubilee Centre website and was republished with permission.

[1] Jon M. Huntsman (2005), Winners never cheat pp. 71-72; Wharton School Publishing, New Jersey.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Jubilee Centre - The cumulative crisis of trust