“I get most of the questions about my faith at work”

Slavik Lytvynenko is an Ukranian research professor in Prague. “Athanasius taught me that work has meaning only when done with the divine perspective in mind”.

PRAGUE · 28 AUGUST 2017 · 12:47 CET

The Czech Republic in Central Europe is one of the most secular countries in the world. There may be fewer than 40,000 evangelical Christians out of a nation of 10.5 million.

Because there are so few Christians, the workplace provides a particularly excellent opportunity to demonstrate the reality of one’s faith.

This interview is part of a series exploring different ways Czech Christians are dealing with the opportunities and challenges of living out their faith in the secular workplace. We hope you find this encouraging as you wrestle with your own situation.

Dr. Slavik Lytvynenko is originally from Ukraine and currently works for Charles University in Prague, primarily researching medieval manuscripts.

This is his story.

Question. Can you tell us a little about yourself? What kind of work do you do?

Answer. My full name is Viacheslav Lytvynenko, and I use a shorter name “Slavik” among family and friends. I came to Prague with my wife, Oksana, and our three children, Helena, Albert, and Renat, from Ukraine in 2010.

The initial plan was to spend three years in Prague so that I could finish my Ph.D. at Charles University, and then go back to Ukraine where I would continue my teaching ministry at Donetsk Christian University (DCU). DCU was the school where I had studied from 1993 to 1996, and later taught church history and theology from 2003 to 2010, prior to our move to Prague.

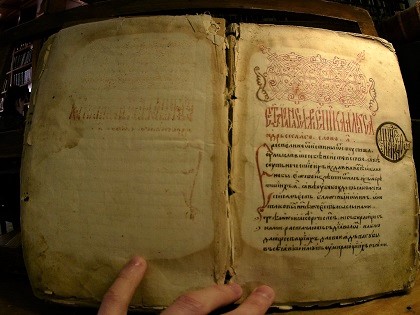

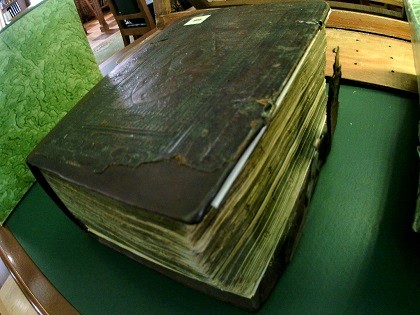

By the time I was about to finish my Ph.D. in 2014, a war began in Eastern Ukraine and DCU was immediately captured and turned into a military base. This completely changed our plans and as we sought God’s leading for our family, I was offered a two year post-doctoral position at Charles University, and my wife and I also joined the Global Scholars mission the same year. By the end of my post-doc, I was hired as a research professor at Charles University, and that is my main job today. As a researcher I work with the medieval manuscripts, and what I do is searching and editing various (mostly Christian) writings that are no longer extant in their original languages (Greek, Coptic, Syriac, and others), but still exist in the Old Slavonic translation.

Q. How did you become a Christian?

A. I grew up in a non-Christian home but was exposed to Christian faith through my grandmother. She was an Eastern Orthodox believer and often took me to church when I visited her. It was a time of Communist ideology in Ukraine, and because Christians were constantly persecuted for their faith, my grandmother’s actions put her under much risk, which I realized only later. When I was fifteen years old in 1990, I was able to get a copy of the Bible for a weekend. A that time, the former Soviet Union was collapsing and while the spiritual hunger was extraordinary, the Bibles were very rare. On the streets of Ukraine they were selling for about six month wages. My exposure to the Bible had a life-changing impact on me, and several days after reading it day and night I was able to find an Evangelical church whose pastor (and my future friend) led me to Christ.

Q. How has your walk with Jesus influenced your professional choices?

A. My becoming a Christian generated in me an enormous hunger for knowledge about God, and after finishing high-school I studied theology in several Universities in Ukraine, Belgium and Prague. Whenever I taught theology myself, it was always in such places as Christian Universities and Seminaries, so the challenge of integration of faith and scholarship was never demanding. It was only when I switched to working with the medieval manuscripts at Charles University in 2014 that I realized the immensity of that challenge as most of my colleagues in that field were non-Christians. In this new work context, I try to be open about my faith, and I am glad to see that this openness has led some people ask me questions about God and Christianity.

Q. Do you think church leaders are aware that the workplace is the main mission field of most people in their congregation?

A. I am fortunate to be a part of a church – the International Church of Prague – in which our leaders do an excellent job of encouraging our congregation to treat the workplace as the main mission field. A lot of people in our community come to Czech Republic for only several years and then leave. Many of them are entrepreneurs, teachers, diplomats, social workers, etc., and our pastor makes every effort to teach us about the importance of using our workplace as a means of showing God’s love and reaching out to other people.

Q. How does your local church support you in the mission field of your workplace?

A. Besides the support that I receive from Sunday morning sermons, our church conducts several practical ministries where I can use my gifts as a way of both building up the community and reaching out to non-believers. There is what we call the Bridge Center where (among many ministries) our church provides a place for University students to meet and have someone from our congregation to talk and encourage them. My church organizes yearly gatherings for those involved in ministry, and we spend time eating, sharing and supporting each other.

Q. Have you had opportunities to talk about your faith with colleagues? What factors made this possible?

A. I am always asked about my faith by non-believing colleagues, and most of the time it happens in the work context. One of my colleagues, with whom I work most closely, never asks me about faith outside of work. Yet, whenever we do things related to work (co-author an article or share presentations at conferences), that is when I get most of the questions, and I find it generally true for most of my work relationships. I rarely have conversations about faith during free time and outside of work, and I feel that so far talking about God in work contexts has been most comfortable for my colleagues.

Q. Is “being light” in your workplace context always talking to people about your faith in Jesus? What other ways have you found to be a fruitful follower of Jesus in your work?

A. My workplace gives me plenty of opportunities for “being light” to my colleagues and students. Of course, the major way of doing this has been through my work, which I strive to perform with excellence and passion. It causes people to wonder why I put so much heart and effort in my work, and I tell them that I do it for God and ultimately for his glory. Whenever I write or teach, I try to make connections between my work and faith in a way that makes my Christian identity clear and explain why I do what I do differently from others.

Q. What types of pressure are most common in you workplace?

A. I feel quite comfortable in my workplace, and the biggest pressure for me comes when I go to other countries to work with manuscripts. Places like Germany, Italy and England are easy to work in, while other places – such as Greece, Russia, Bulgaria, and Serbia – tend to have stricter rules on accessing the manuscripts. Another type of pressure comes during conferences, where the general expectation is that scholarly language excludes anything that smacks Christian. This expectation is especially strong in the Czech Republic, where it appears as if one is supposed to be either a Christian or a scholar, but not both. So, whenever I see people being surprised that I am both, I try to use it as an opportunity for a conversation, and doing this somehow strengthens me.

Q. What resources have helped you most in your Christian thinking about your work?

A. There are a couple of books that have been especially helpful for me as a Christian scholar. The first one is written by William R. Yount, Created to Learn: A Christian Teacher’s Introduction to Educational Psychology (B&H Academic; 2nd edition, 2010). I translated it into Russian in 2001 before the author published the second edition of his book in 2010, and I could recommend it highly to everyone who is involved in education. The author offers a very helpful discussion of various theories of teaching and learning and does an exceptionally great job of explaining what it means to be a Christian educator.

Two other books that affected me deeply were written by ancient writers – one is Plato’s Republic (especially chapter 7), and the other is Life of Saint Antony written by a fourth-century Christian thinker Athanasius of Alexandria. Both writings offer profound, and truly classic, insights into human nature, and while Plato’s perspective is based on what he could perceive of God from nature, Athanasius draws from Scripture and Christianizes ancient Platonism. Whereas Plato taught me that to do good work one needs to be a good human, Athanasius taught me that work has meaning only when done with the divine perspective in mind.

Read the first interview of these series, with Šárka Konícková.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - life & tech - “I get most of the questions about my faith at work”