The ‘Complutense Polyglot Bible’: a Spanish Catholic work that paved the way for Protestants

This Bible is the perfect example of the Renaissance's emergence in the Hispanic world, closely linked to the defence of Roman Catholicism and to the memory of 16th-century Spanish Protestantism.

14 NOVEMBER 2025 · 11:35 CET

I remember the exact moment when I first learned of the existence of this object: among all the printed books that our professor was guiding us through in the Complutense Historical Library, this Bible caught my attention.

Firstly, because, as a lover of dead languages, recognising the Greek alphabet among those pages revived my interest in the class.

Secondly, the Protestant in me was thrilled to see with my own eyes the original biblical text that existed in our country, even before Luther published his famous theses.

From then on, I became increasingly interested in the Spanish evangelical movement and gradually discovered names, events and dates that completed the big puzzle in my head.

All Evangelical Focus news and opinion, on your WhatsApp.

That is why, on this anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, I wanted to return to this object, which may be largely unknown to many.

It is the Complutense Polyglot Bible, a perfect example of the emergence of the Renaissance in the Hispanic world, closely related to the defence of Catholicism and, in turn, to the memory of Spanish Protestantism in the 16th century. But how is this curious and ironic relationship possible?

The Complutense Polyglot Bible

Conceived by Cardinal Cisneros (1436-1517), this Bible consists of six volumes in which the text can be read in both Latin and the biblical languages: Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek.

The printing work, carried out by Arnaldo Guillén de Brocar (1460-1523), took place between 1514 and 1517, although it was not published until it received the placet (‘approval’) of Pope Leo X.[1]

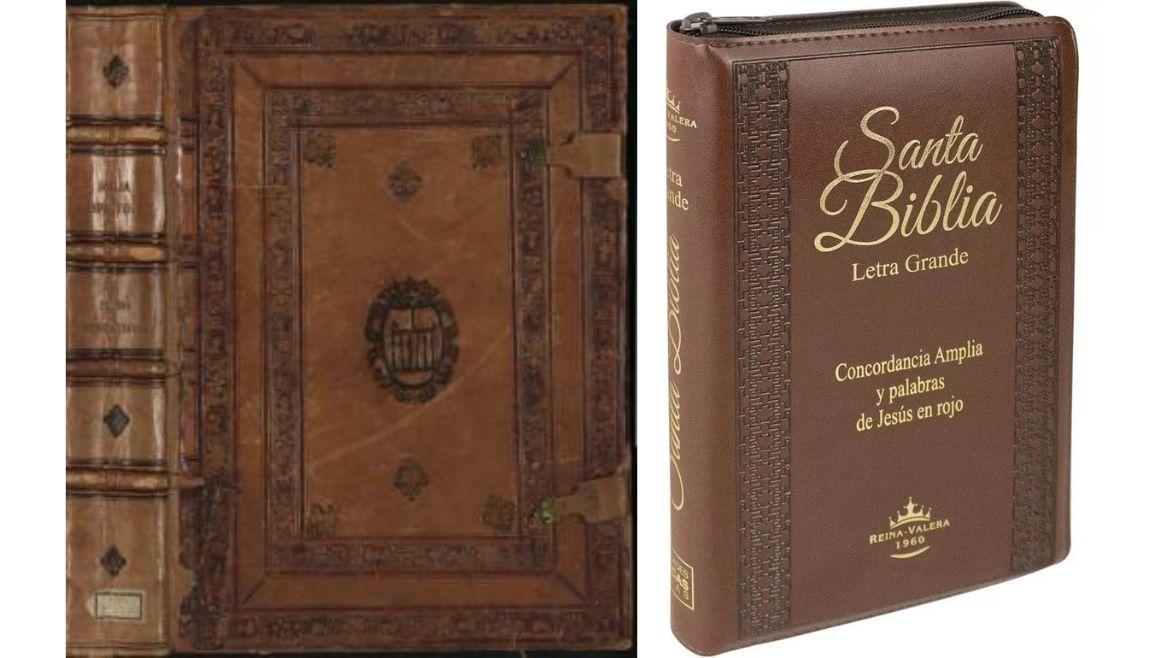

The exterior of the Polyglot in this image is not so different from what we might find in the Bibles on our bookshelves today: brown covers decorated using the dry embossing technique (i.e., with metal plates applied with pressure and heat to the covers).

However, what we see is not the original binding of this collection. We can imagine that, in its day, two leather-covered wooden covers embraced the pages, carefully sewn by hand to form several booklets.

These sections, in turn, would have been joined together to form the whole book, creating five seams that were elegantly marked on the spine of the volume, as if they were the vertebrae supporting that body of paper.

At least, this is how other copies whose original binding has been preserved were put together.[2]

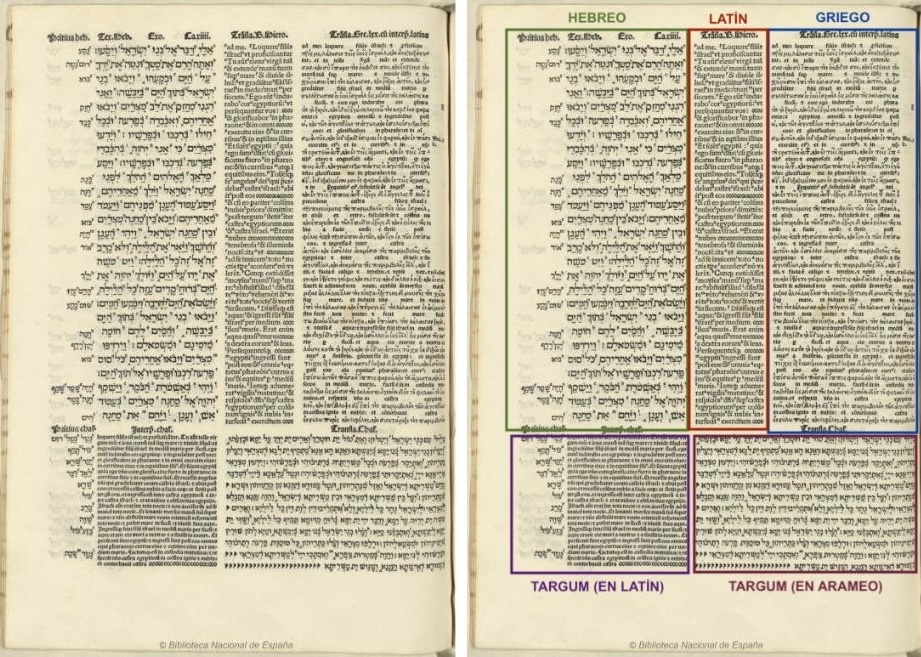

As for the interior, there is a difference in the organisation of the text in each volume of the Bible.

The first four, corresponding to the Old Testament, have the Latin Vulgate in the central column, with the Greek Septuagint —and its interlinear translation into Latin— and the Hebrew text in the outer columns. In contrast, the fifth volume, dedicated to the New Testament and the first to be printed, has the Vulgate version and the Greek text. [3]

The sixth volume is a grammatical appendix of Hebrew, interpretations of Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek names, and a dictionary of Semitic languages.[4]

In the case of the first volume (dedicated to the Pentateuch), a lower section is added to this layout, which includes the Targum, that is, the Aramaic translation of the Hebrew text.

These translations (targumim) were made between the 1st and 8th centuries AD by Jewish communities in response to the need to translate the text into what had been their lingua franca for centuries.

However, in addition to a translation, the targumim incorporated interpretations and paraphrases ‘that document very well the meaning attributed to the verse,’ according to the editors of the Complutense Polyglot.

More specifically, this work includes the Targum of Onkelos, the Aramaic version of the Torah, under the title Translatio Chaldaica (‘Chaldean Translation’) accompanied by a Latin translation (Interpretatio Chaldaica) prepared by the editors of the Bible. [5]

I mention this because it is striking—perhaps even contradictory—that, just a few years after the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula (1492), it was decided to include a translation with an interpretation that was particularly popular in Sephardic communities.

However, Cisneros himself clarifies that this translation was included because ‘those places that are not corrupt favour the Christian religion’, while the Targumim of the rest of the Hebrew Bible would have been rejected as ‘unworthy of appearing alongside the sacred books’. [6]

The desire for the Polyglot to achieve exceptional quality led its printer to design from scratch his own exclusive typefaces for this work. Robert Proctor, a 19th-century librarian and expert on incunabula and typography, stated that the Greek typefaces used in the New Testament are ‘the best Greek font ever created’. [7]

In contrast, the Greek typeface used in the Old Testament, published later, seems a little less elegant, according to translator Juan Gabriel López Guix.[8]

This decision might perhaps seem to be the result of the exhaustion of a printer who casts hundreds of small pieces and then places them with great care on the frame over and over again, but nothing could be further from the truth.

Roman Catholicism and the Renaissance in the Complutense Polyglot

Everything in the Polyglot Bible was meticulously planned to show the supremacy of Christianity, as exemplified by the publication of the New Testament volume before the other five.

The movable type used was no less important, as the elegance of the Greek characters in the New Testament shows the superiority of the writings referring to the life of Jesus Christ and his first disciples.

Likewise, the Vulgate (i.e., St. Jerome's version) was the pillar of Roman Catholic orthodoxy and the text that prevailed in any doctrinal doubt, so the distribution of the columns is equally intentional.

The preface states this clearly: ‘We have placed St Jerome's version between these two, that is, between the Synagogue (Hebrew version) and the Orthodox Church (Greek version).

Just as the Roman or Latin Church places Jesus between the two thieves’. [9] And the Jewish Targum, despite being included, is placed below the biblical text, as if Judaism were being trampled on by Christianity.

Art historian Anna Muntada Torrellas sees an architectural component in this organisation.[10]

The columns would support the text just as they would support a Renaissance Roman Catholic temple, such as the one that was beginning to be built in the Vatican.

As Anna rightly points out, order, reason and proportion are features of Renaissance architecture that we could well use to describe the Polyglot. And perhaps each of the biblical languages has its own style, whether Doric, Ionic or Corinthian, which ‘adorns the doctrine of God’. [11]

The Polyglot and the Great Commission

But in the Polyglot Bible we find something that goes beyond these Renaissance connections. Behind the arduous philological work lies a certain didactic and evangelistic zeal that derives directly from Jesus' words to his disciples:

‘Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.’ (Matthew 28:19-20).

The well-known passage of the Great Commission shows the task in which all Christians should participate: making disciples by teaching. This task is related to the Complutense Bible in a kind of docendo disco (‘by teaching, I learn’)[12].

Why offer an interlinear translation into Latin of other languages? Why this need not only to compile the original sources, but also to know what they say? Wasn't the Vulgate enough? Was Cisneros challenging the Vulgate at the same time as he was exalting it?

Whether he did so consciously or not, the truth is that ‘knowledge of the original languages opens up direct access to the Bible’[13] and, by extension, to God.

Understanding the revealed words in their original language allowed them to be compared with the Vulgate, to know the full meaning of certain terms and to discover whether some words or interpretations had perhaps been added later.

But the key question is: who was allowed to do so? Only those who could read Latin and could afford to access this copy, so that, although he was making the Bible and God accessible, he was only doing so to a few.

Sola Scriptura, Reformation and Polyglot Bible

A cross-cutting issue in Luther's concerns is his passion for Scripture as a source of knowledge of God, the famous Sola Scriptura. And if ‘the word of God is living and powerful, sharper than any two-edged sword’, if ‘it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow’ and ‘discerns the thoughts and intentions of the heart’ (Heb 4:12), it is not surprising that the German wanted that sword to pierce the hearts of as many people as possible.

Martin Luther also followed the principle of ‘making disciples.’ But unlike Cisneros, Luther advocated for the translation of the Bible into vernacular languages—as did others before him, such as the Englishman John Wycliffe (1328-1384).

In the words of historian Rafael Lazcano, ‘by reading the Holy Scriptures in the vernacular, Luther sought to win the common German man over to the faith in Christ and to an encounter with God, not distant or hidden, but close at hand through faith alone, merciful, generating trust and saving love.’ [14]

The connection between the Polyglot and Protestantism is such that Cipriano de Valera (16th century), co-translator of the famous Reina-Valera Bible, conceived and produced his version as the heir to the polyglot Bibles of Cisneros and Arias Montano.

Valera admired these multilingual endeavours, ‘claimed them for the cause of spreading the word of God’ and considered his work to be connected to them, albeit in a more limited linguistic sphere. [15]

Conceived by Cisneros, Inquisitor of Castile between 1507 and 1517, everything about the Complutense Polyglot Bible was intended to emphasise the superiority of the Church of Rome and its doctrine.

However, less than a century after its printing, this staunch Calvinist presented himself as the successor to the path that the Polyglot had opened up. Is this true? Could a repressor of heresy have created something that was in turn claimed by religious dissidents?

After this analysis, the answer to these questions can only be yes: the desire to delve deeper into the texts that gave meaning to his worldview is what unites Cisneros and his Polyglot with Protestant beliefs.

Perhaps without knowing it, Cisneros was providing the curious people (and later considered heterodox) with a powerful tool to access the original meaning of the divine words.

And the meaning they interpreted ultimately led them to break away from the Roman Catholic Church.

However, even though each branch took its own course, the Polyglot Bible unites the two in a unique way, making it clear that there was something—or rather, Something—in common between people as disparate as Cisneros and Cipriano de Valera.

Notes

[1] Luis Díez Merino, El Targum Onquelos en la tradición sefardí, Estudios Bíblicos 57 (1999): 205-225, esp. 207.

[2] Antonio Carpallo Bautista y Juan Bautista Masso Valdés, Las encuadernaciones de la Biblia Políglota Complutense, Pecia Complutense 11 no. 20 (2014): 1-16, esp. 6.

[3] To go deeper into the philological aspects of this Bible and its sources, I recommend the catalogue of the exhibition on the 500th anniversary of the Complutense Polyglot Bible, held by the UCM in 2014. It is also useful to consult the volume published in 2014 by the University of San Dámaso, entitled Una Biblia a varias voces. Estudio textual de la Biblia Políglota Complutense.

[4] José Bonifacio Bermejo Martin, La Biblia Políglota Complutense y la edición en el siglo XVI, El Cardenal Cisneros en Madrid: Ciclo de conferencias (2017): 101-112, esp. 102.

[5] Diéz Merino, El Targum…, 213.

[6] Diéz Merino, El Targum…, 214.

[7] Robert Proctor, The printing of Greek in the Fifteen Century (Oxford: Bibliographical Society at the Oxford University Press, 1900), 144: “To Spain belongs the honour of having produced as her first Greek type what is undoubtedly the finest Greek font ever cut”.

[8] Juan Gabriel López Guix, Biblias políglotas y traducciones bíblicas al castellano en el siglo XVI, TRANS: Revista de Traductología 25 (2021): 17-60, esp. 21-22.

[9] Translation of Anna Muntada Torrellas, Del Misal Rico de Cisneros y de la Biblia Políglota Complutense o bien del manuscrito al impreso, Locus Amoenus 5 (2000): 77-99, esp. 97.

[10] Muntada Torrellas, Del Misal Rico…, 95.

[11] Titus 2:10. “Not to steal from them, but to show that they can be fully trusted, so that in every way they will make the teaching about God our Savior attractive”.

[12] “By teaching, I learn”, an expression derived from the Latin quote ‘homines, dum docent, discunt.’ (Sen. Ep. 7. 8). The word ‘disciple’ comes precisely from the verb discere.

[13] Muntada Torrellas, Del Misal Rico…, 96.

[14] Rafael Lazcano, Un paseo por las obras de Lutero, Revista de historiografía 32 (2019): 107-118, esp. 117.

[15] López Guix, Biblias políglotas…, 52.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - European perspectives - The ‘Complutense Polyglot Bible’: a Spanish Catholic work that paved the way for Protestants