Pentecostalism in African Christianity

The formation and scope of a distinctive spirituality.

16 FEBRUARY 2021 · 18:50 CET

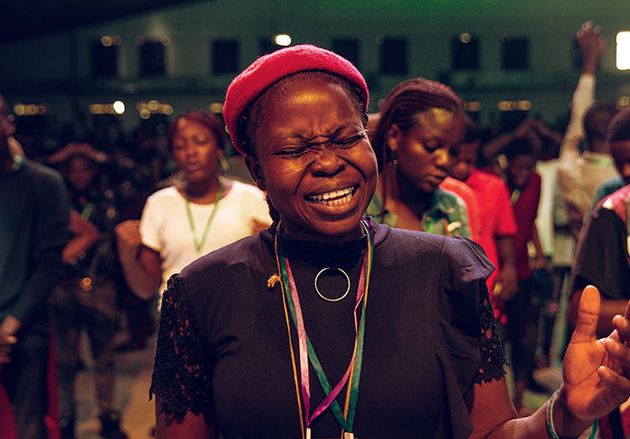

In almost all denominations in Africa, one can recognize the profound influence of Pentecostal spirituality.

Whether they worship in an Anglican or a Methodist church, African Christians offer exuberant songs of celebration to the Lord, often with overwhelming emotion.

Spiritual warfare and exorcism are everyday ministries for African pastors. African Christians’ strategic response to the influence of globalization has produced a creative synthesis which combines the universal truth of Christianity with charismatic spirituality born out of their tradition.

Precursors of Pentecostalism in Africa

Several distinct groups were fundamental to the shaping of charismatic spirituality among African believers.(1) To comprehensively understand African Pentecostalism, it is important to situate it within the trajectory and context of Africa’s appropriation, historically and continuing today, of the pneumatic dimension of Christianity—that is, African Christians’ awareness of the spirit world and focus on the Holy Spirit.

-

The earliest forerunner of the twenty-first century’s Spirit-infused African churches was Kimpa Vita, an eighteenth-century traditional diviner in the Kingdom of Kongo who claimed to be possessed by the spirit of St. Anthony. She became an important prototype to religious leaders who created a new synthesis by appropriating Christian symbols and messages to their traditional religions.

-

The second group of precursors, in the late nineteenth century, were African prophets from the ranks of Christian tradition who called for moral and spiritual reform based on the pneumatic aspect of Christianity. William Wadé Harris in West Africa, Isaiah Shembe in South Africa, and Simon Kimbangu in Central Africa belong to this category.

-

In the early twentieth century, among African Instituted Churches (AICs), a wave of ‘Spirit-type’ churches arose that were marked by a focus on healing and prophecy. Some of them developed into loosely organized denominations such as Aladura in West Africa and Zionist in Southern Africa. Emphasizing divine healing and supernaturalism, they imbued some traditional rituals and symbols with Christian meanings.

-

The last group of precursors were spiritual renewal movements within mainline denominations, such as the Balokole Revival that took place beginning in the 1930s in the Anglican Church of Uganda. Calling attention to spiritual laxity and moral failure in the church, these movements strived to revitalize nominal Christians by emphasizing the transformative work of the Holy Spirit for a deeper spiritual life.

The remarkable emergence of Pentecostal churches in Africa in recent decades should be understood as the cumulative effort of renewal movements that took place in Africa over the previous century.

Africans’ pivotal roles in these movements shaped and deepened charismatic spirituality in the various denominations of Africa’s Christian churches.

Current trends in African Pentecostalism

1. Adaptation to various cultures and traditions

Pentecostal Christianity has demonstrated a unique ability to adapt itself to diverse cultural and religious traditions.(2) Instead of rejecting a culture’s traditional belief in the existence or power of spirits, Pentecostals demonize those spirits as entirely evil. Behind this complex process is a thoroughgoing dualism: the Pentecostal worldview divides the world into good and evil, those who follow God and those who follow the devil.

By presenting the Holy Spirit as a good and more powerful spirit, Pentecostal dualism allows its adherents to maintain their indigenous spiritual cosmology and even ritual engagement with traditional spirits through Christian spiritual warfare and exorcism.

2. Promotion of modernity

From the outset, Pentecostalism has gone hand-in-hand with modernity in rapidly changing contexts. Pentecostalism can offer varied forms of social and spiritual empowerment to the marginalized so that they may move toward a better life.

Pentecostals in urban African settings embrace modern characteristics such as individualism, capitalism, and gender equality. They believe each person—not a family or tribe—is responsible for his or her salvation (individualism); they pray God may help them find a job in a new capitalist labor market (capitalism); they learn that they should treat their spouses more kindly, and turn away from adultery (gender equality).

African Pentecostals have been proactive in forging their own modernity through what they learn from the modern, global faith community.

3. Appeal to laypeople and women

Many African lay Christians—especially women and the uneducated, who were previously underrepresented in the church leadership—find the egalitarian ethos of Pentecostalism extremely appealing.

Pentecostal theology holds that religious authority resides in a person with spiritual gifts, not in a religious bureaucracy; relatively low value is placed on theological education or official ordination.

This core belief opens up a vast number of opportunities for laypeople and women to serve as preachers, evangelists, and healers in the church. For instance, to mobilize its congregation for various church ministries a Pentecostal megachurch in Uganda recently introduced a new slogan that ‘every member is a minister’.

4. Liturgical innovation

Pentecostals are well known for their extensive use of mass media and popular culture. Open-air crusades featuring renowned evangelists are a typical outreach to non-believers.

Electronic musical instruments are so important to the worship ministry of African Pentecostals that even congregations that cannot afford to keep their church building well maintained consider it essential to have a full band and a quality sound system.

Young people are eager to learn contemporary songs from Hillsong Church in Australia.

Many Pentecostal churches in Africa have their own YouTube channel (and even broadcasting studio) to stream live music in public places.

The spontaneous, experiential, and exuberant elements of Pentecostal worship offer liturgical alternatives compatible with African religiosity.

Important contemporary issues in Pentecostal movements in Africa

1. The prosperity gospel

Pentecostal churches have been often criticized for their emphasis on the material blessings of health and wealth. The Cape Town Commitment raises significant concerns, noting that ‘the teachings of many who vigorously promote the prosperity gospel seriously distort the Bible’(CTC II-E-5).(3)

Historically many false prophets—not only in Africa, but also all over the world—have promised material blessings in return for generous giving. (4)

It is important to note, however, that the African concept of prosperity is significantly different from the American understanding of it. To Americans, prosperity means having a new vehicle or a larger house. To Africans, on the other hand, prosperity means having an adequate meal or access to basic medical care. As we can see from what Jesus taught about prayer, it is completely biblical to pray that God will meet our daily material needs.

Therefore, we should resist the tendency to generalize about the religious beliefs of African Pentecostals and assume they line up with what we know about American Pentecostalism.

Currently, many African pastors are well informed about the theological problems related to the prosperity gospel. A prominent Pentecostal pastor in Uganda, for example, asserts that he has never allowed the prosperity gospel to be preached in his church.

A very experienced Methodist pastor in Burundi explains that the prosperity gospel has a strong foothold in independent churches that lack formal structure and theological education. Thanks to the combined efforts to counter the prosperity gospel, its prevalence in African churches has declined in recent years, especially in major denominations.

2. Globalization and multiculturalism

African Pentecostals clearly are aware of the global nature of Christianity. They celebrate it as a positive contribution to their faith journey. Young Africans living in urban areas are interested in connecting with the external world in all possible ways.

That is probably why in many parts of Africa multicultural congregations are flourishing much more than traditional mono-cultural churches.

Two notable examples of multicultural churches are Christian Life Ministries (the fastest-growing church in Burundi) and Christian Life Assembly (the fastest-growing church in Rwanda).

These sister churches led by multicultural pastoral teams (from Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Canada, and the UK) have attracted young professionals and students from twenty different countries through modern-style worship services and culturally sensitive discipleship programs.

This type of multicultural charismatic church is hard to categorize; technically speaking, they do not belong to either AICs or classical Pentecostal churches. They illustrate the complexity of globalization’s impact on African Pentecostal churches.

We should be careful not to assume that the Pentecostal movement worldwide has a monolithic character. Any definition of Pentecostalism needs to be pluralistic in nature.(5)

3. Holistic understanding of the universe

Africans’ belief in the invisible spirit world has been fundamental to the phenomenal growth of Pentecostalism in Africa. Perceiving the world as a constant interplay between physical and spiritual forces, African Pentecostals emphasize the critical role of the Holy Spirit in their lives.

They hold a holistic understanding of the universe in which one cannot draw a neat boundary between the visible and the invisible.

Many contemporary Africans who are thoroughly integrated into the modern world retain their traditional cosmology. It is common to regard disease, misfortune, and relational conflict as forms of spiritual attack.

Africans are not perplexed when they encounter someone possessed by an evil spirit. Prayer for exorcism and healing is part of the ordinary ministry of most African churches; they actively engage in spiritual warfare as a way to serve members who are in spiritual turmoil. (6)

An Anglican clergy in Burundi describes how he is called on frequently, day and night, to pray for the demon-possessed. It seems unlikely that this holistic understanding will change anytime soon.

Conclusion

African Pentecostalism should not (and probably cannot) be understood in purely theological terms. Its experiential and spontaneous nature makes it challenging to fit African Pentecostalism into the neat category framed by philosophically oriented Western theologians.

As Timothy Tennent foresaw a decade ago, the time is ripe for the extensive application of interdisciplinary and cross-cultural Christian theology to mission movements in the world. (7)

In the case of African churches, the so-called ‘charismatization of African Christianity’ ought to be recognized and celebrated as Africa’s successful attempt to establish a distinctive spirituality that appeals to Africans’ understanding of the universe.

Daewon Moon is the senior pastor of Daegu Dongshin Church in South Korea. He serves on the boards of Global Lausanne, Korea Lausanne, Korea World Missions Association (KWMA), and Global Missionary Fellowship (GMF).

Daewon received his MDiv from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and his PhD in World Christianity from Boston University

This article originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission. To receive this free bimonthly publication from the Lausanne Movement, subscribe online at www.lausanne.org/analysis.

Endnotes

1. Ogbu Kalu, African Pentecostalism: An Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, African Charismatics: Current Developments within Independent Indigenous Pentecostalism in Ghana (Leiden: Brill, 2005).

2. For a sociological analysis of Pentecostalism, see Joel Robbins, ‘The Globalization of Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity,’ Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (2004): 117–43; Joel Robbins, ‘On the Paradoxes of Global Pentecostalism and the Perils of Continuity Thinking,’ Religion 33 (2003): 221–31.

3. https://www.lausanne.org/content/ctcommitment

4. See article by Moses Owojauye, entitled ‘The Problem of False Prophets in Africa: Strengthening the Church in the Face of a Troublesome Trend,’ in November 2019 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2019-11/problem-false-prophets-africa.

5. Allan Anderson, An Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

6. See article by J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu, entitled ‘Spiritual Warfare in the African Context: Perspectives on a Global Phenomenon,’ in January 2020 issue of Lausanne Global Analysis, https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2020-01/spiritual-warfare-african-context.

7. Timothy C. Tennent, Theology in the Context of World Christianity: How the Global Church is Influencing the Way We Think about and Discuss Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2007).

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Lausanne Movement - Pentecostalism in African Christianity