A dark and stormy night

Frankenstein is one of the strongest warnings against the horror of trying to play God.

19 JUNE 2015 · 13:43 CET

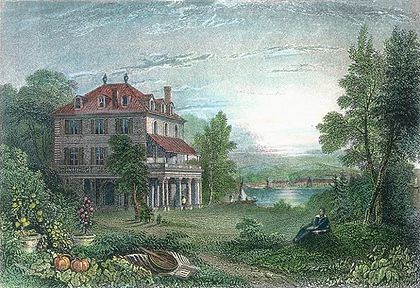

Over the last few days spent in Geneva, I have fulfilled my teenage dream of visiting Villa Diodati. It is the house in which, on a “dark and stormy night”, saw the birth of two legends whose terror grips us still, the monster and the vampire. In the summer of 1816, Lord Byron and his doctor and secretary Polidori rented the house of the family of the Bible translator and Calvinist reformer, Giovanni Diodati. Percy and Mary Shelley were at the house one day reading ghost stories as the rain battered the window panes when, on the eve of my birthday – 17 June –, they decided to each write a horror story. Mary created Frankenstein and Polidori created the Vampyre.

Mary was the daughter of a writer who had abandoned Presbyterianism – her grandfather was Godwin, a renowned Calvinist preacher from Cambridge–, to marry a pioneer of feminism, Mary Wollstonecraft – who had published “A vindication of the rights of women” in 1792–. Mary’s mother died giving birth to her and she was brought up by her father, who was a strong believer in man’s inmate goodness and in all-powerful reason. However, that free thinker and prophet of free love opposed the relationship between his daughter and Shelley, a married man with children.

Percy and Mary left England, like Byron, to escape the scandal that surrounded them. They had just had a son, after losing a daughter, when Mary’s step-sister and Percy’s wife both committed suicide. They took another of Mary’s step-sisters, Claire Clairemont, with them to Switzerland. She was carrying Byron’s child but attracted Percy who encouraged a friend of his to enter into a relationship with Mary. If that weren’t enough, alongside this exchange of partners, stood the hatred that Polidori felt for Byron, who humiliated him constantly, becoming the vampire in his story. Polidori ended up committing suicide, overcome by his addiction to gambling and his repressed homosexuality.

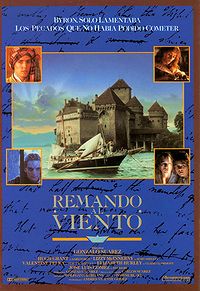

ROWING WITH THE WIND

This episode was popularized on screen by the Spanish director from Oviedo, Gonzálo Suarez, who made captured the events of that night in his film“Rowing with the wind” (1988). Although it is a Spanish production, the actors are English. In fact, it was during the filming that Hugh Grant and Liz Hurley met for the first time. The coastal scenes were filmed in Asturias, but the interior of the mansion are taken from a house on the outskirts of Madrid, although the view of the lake and Chillon Castle, were filmed in Switzerland, where I was recently able to visit this medieval fortress near Montreaux.

I remember the feeling of going back to my bedroom, after living on my own. There I had the biography of Lord Byron which is now lying on my desk. His story obsessed me when I was a teenager, this episode in particular. It was bizarre to see on screen what I had up till then only imagined. Now I understand that its coldness comes from the subject that it deals with: death.

One of the most beautiful scenes – as Javier Tolontino observes in the booklet that accompanies the DVD– is Shelley’s body, burning on the beach. It is based on a painting which has fascinated me from the first time that I saw it. It shows a bluish afternoon with violet tints, where the people are wearing black, looking out to a swelling sea, from the shores of a crumbling Italy. All of this is accompanied by the lyricism of Vaughan Williams’ music. I also like the light of the stormy night, by the warmth of the fire, a far cry from my Spanish summers.

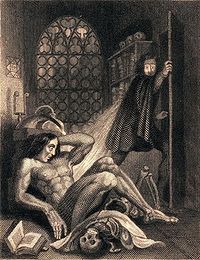

Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” begins by the creature’s search for its creator, the doctor by that name – many people mistakenly think that it is the monster’s name–. He is an Italian brought up in Geneva, like Diodati. While practising alchemy in search for a life elixir, he creates a humanoid, in an attempt to produce life from inanimate matter. On realising the horror that he has unleashed – he calls him his enemy or Demon –, he pursues him throughout the Artic, to destroy him.

In Suarez’s film, following a short quote from Byron’s poem “Darkness”, we see a frozen ocean as an arid landscape where there is nothing but death. There are large blocks of ice which he navigates through in a flimsy vessel carrying Mary Shelley, paralysed by the cold. In her heart-rending confession to Byron, she says that the monster is her double, exploring the innermost corners of her soul:

Against the laws of nature, I brought that unspeakable creature to life. It is nothing other than the result of my ambition and pride. I should never have done it (…) I am talking about myself; the monster is in me, I can feel it. I know that my creature and the spirit that moves it is made from matter. It comes from me, from the moment I was born, I killed my mother, long before he got rid of me…

PLAYING GOD

Frankenstein is yet another strong warning against the horror of trying to play God. It is what humanity has been trying to do since Eden. Not only do we want to discover good and evil for ourselves (Genesis 3), but we adore and serve mere creatures (Romans 1). We give ourselves over to a way of thinking that doesn’t take God into account (v. 28). Frankenstein shows us that such a rationale produces monsters.

Keller says that idols are things which arouse expectations in us that only God can fulfil. That misplaced trust distorts not only our mind but also our feelings. When idolatry governs our heart, it redefines how we see reality. What is good can appear to be evil, and evil can appear to be good. It can also create paralysing fear. The anxiety that we see in Frankenstein, comes from his inability to change the past. This produces and unalterable sense of guilt which, in the present, is manifested by anger and despair.

We cannot remove the idols from our heart, as Thomas Chalmers observed in his well-known sermon. They need to be replaced. If you uproot them, they will grow back, or will be substituted by others. It is not enough to repent of our idolatry or to use our willpower to live differently. According to the Scottish preacher, we need the love of Christ, which displaces any other love.

That is the admiration that we call worship, which replaces the idols in our heart. Because, what is faith, as Grau used to say, if it is not “allowing God to be God”? When we play God, we want more freedom and control, but in the end we end up becoming more enslaved. It is only the truth of Christ that sets us free (John 8:31-36). Any other rationale produces monsters…

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - A dark and stormy night