“African Pentecostalism has grown large enough to begin to influence world Christianity”

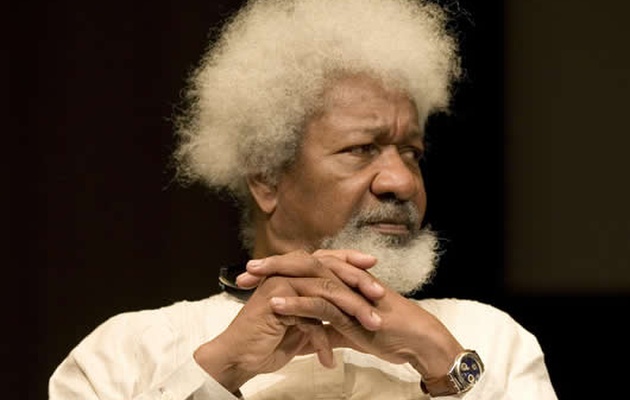

African theologians Harvey Kwiyani and Abraham Waigi assess Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka’s harsh criticism of the increasing influence of churches on the continent

LIVERPOOL · 20 DECEMBER 2021 · 11:45 CET

Recent statements of Wole Soyinka, the first African to be honoured with a Nobel Prize in Literature back in 1986, paint a very dark picture of the developments of Christianity in Africa.

For Soyinka, both Islam and the Christian faith have been used to exploit the needs of the population, and to sustain corrupt governments. Both the proliferation of Christian cults and violent Islamist movements have hindered the progress of Africa, says the influential cultural analyst.

Evangelical Focus wanted to know more about the thinking of the Nigerian author and the background of his criticism. We asked two African theologians how they see the issues raised by Wole Soyinka.

Harvey Kwiyani (originally from Malawi) is a mission-theologian currently serving as CEO of Global Connections in England. He also lectures at Church Mission Society in Oxford where he leads a Master’s Program in African Diaspora Christianity. Abraham Waigi is a lecturer at the Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology, Mission, and Culture in Akropong (Ghana). He studied the works of Wole Soyinka for a PhD research.

Theologians Harvey Kwiyani and Abraham Waigi.Question. How has a respected intellectual like Wole Soyinka come to the conclusion that Christian churches in Nigeria and in the rest of Africa are a “

Answer. The introduction of Christianity by Europeans to Africa has always been problematic to many African scholars and writers focusing on Africa's history and cultures. To a great extent, this is because Christianity has taken root in sub-Saharan Africa during the era of European colonisation of the continent and, in the eyes of most Africans, European missionaries and colonisers had one and the same agenda and worked hand in hand to discredit and eliminate African cultures and replace them with European ones. This was done in the name of civilisation.

To convert to Christianity, Africans had to do away with their cultures and identities and begin a journey towards civilisation as modelled by Europeans. To them therefore, Christianity was the anti-thesis of everything African.

Consequently, Soyinka is far from being the only one concerned about the negative impact of Christianity in Africa, and it is not only Africa he is concerned about. He has made the same remarks about Christianity in the United States of America where leading figures have demonstrated a similar proclivity to perversion of power and spirituality.

“The introduction of Christianity by Europeans to Africa has always been problematic to many African scholars”

In his extensive writings, he is clear that wherever and whenever these evils exist, whether it is apartheid in South Africa or genocide in Asia or racist corporate greed in North America, they must be called out, no matter the perpetrator or the consequences.

His plays particularly (for instance, The Trials of Brother Jero and Jero’s Metamorphosis, both first produced in Ibadan in 1960 then published in 1964; The Lion and the Jewel, first produced in Ibadan in 1959 then published in 1963; and Madmen and Specialists, first produced in New York in 1970 then published in 1971) provide ample evidence for this sensibility.

Soyinka’s activism against such societal evils has resulted in personal suffering, noteworthy being the 22 months he spent in solitary confinement, as well as several forced and voluntary exiles.

Wole Soyinka. / Photo: Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism. Q. In a recent interview, Soyinka said it is bad news that religion is more present in Africa now than some time ago. Christianity (as well as Islam, he says) “impose their views”, “use fear to dominate people”, and “exploit of vulnerable people”. Is this view of Christianity in Africa well-balanced?

A. Africa has witnessed a phenomenal growth of Christianity starting in the 1960s. Islam has been growing as well, but at a much slower pace. Both Christian and Islam agencies have brought foreign cultures and values that have resulted in significant impact on the African economic and social-cultural context. While Islam takes over and reconfigures a culture to make it reflect its Middle Eastern origins, Christianity (and by this, we mean Christian agencies/missions, churches or theologians) attempt to contextualise itself to become African. Unfortunately, Christians have had very little success at contextualisation in Africa and, therefore, many African Christians tend to copy the Western cultures of the missionaries and the global Christian media empires.

Having expanded as a civilising religion during the era of European colonialism, the growth of Christianity in Africa in the decades after the 1960s has revealed a tendency to reject European patronage, choosing either to ‘pentecostalise’ (to various extents) and, following American-styled expressions of Christianity, to globalise or to embrace a new identity as independent African denominations.

This globalisation of African Christianity has been influenced greatly by American Evangelicalism and with this came the legitimisation of celebrity-styled preachers and the prosperity gospel which has, in turn, led to some African evangelical and Pentecostal preachers using fear to dominate and exploit vulnerable people.

In Western discourses on African Christianity, these prosperity-preaching ministries dominate the conversation. However, a majority of African Christians, especially in rural Africa, have no clue what it is.

Soyinka is against charlatanism, fundamentalism and extremism in religion. He has written and spoken at length about what he perceives as the imperialist tendencies in the two leading religions. He gives many examples of abuse of power and the weaponisation of fear in his creative writings as well as in newspaper articles, lectures (particularly the 2004 BBC Reith Lectures that resulted in his book, Climate of Fear), and other works.

What is particularly troubling here is his tendency to demonise all religion without acknowledging the good that it stands for.

Q. The Nobel Prize winner also speaks of “cults” who offer “a better life, using the misery of people to generate hopes for a better life” and criticises churches that “embrace political power”. Is this prosperity theology, on one side, and the merging of politics and religion, on the other, so obvious in Africa?

A. African Christianity exists in a context where human life itself is, for many, a challenge. Poverty, diseases, and conflicts—a great deal of this coming out of continued economic colonisation of the continent by foreign powers—make life difficult. For all these problems Africans have always relied on charismatic leaders of traditional religion.

Now, in the 21st century, that religion is Christianity. Of course, just like it would happen elsewhere, money-hungry preachers take advantage of gullible, vulnerable and desperate people. In a context like this, money brings power and power brings more money. Political power becomes enticing, especially as a means for some Christian leaders to accumulate riches. However, this is not unique to Africa. It happens in other parts of the world.

Although Soyinka does not describe these cultic tendencies or the exploitation of the faith of the vulnerable as prosperity theology (he deliberately avoids any term or concept that point to a transcendent reality), he is nonetheless right in condemning them. His critique is valid. We ought not dismiss it just because he opposes Christianity.

Q. There are tens of thousands of Christian churches in Africa. How would you describe their diversity - theologically, organisationally, in matters of influence?

A. Over the past 50 years, the number of Christians in Africa has grown five-fold, from just above 100 million in 1970 to almost 700 million in 2020.

All major Western denominations have members in Africa, and to be relevant in African cultural sensibilities, they have all, to varying degrees, faced the need to ‘pentecostalise’. As such, African evangelicalism comes with Pentecostal and Charismatic flavours. Many mainline churches have taken on Pentecostal tendencies (if only to stop the exodus of their members to Pentecostal churches).

African Pentecostalism has grown large enough to begin to influence world Christianity—African Pentecostals are key players on the European Christian scene. Largest among them are the Redeemed Christian Church of God from Nigeria and the Church of Pentecost from Ghana, both of which have presence in more than 100 countries in the world.

Still, the Roman Catholic Church is the largest denomination in Africa, being home to almost 60 percent of African Christians. African initiated churches (those started by Africans without any support or influence from Europe or North America) have also continued to grow.

Q. What encouraging Christian movements do you see in Africa? What trends among Christian communities give you hope?

A. The phenomenon and vibrancy of Christianity in Africa is always a matter to celebrate. Current trends point to the likelihood that the numbers will continue to grow for another generation or so.

A great deal of that growth will come from biological multiplication of African Christians. Millions of babies being born to Christian parents each year will keep Christianity growing faster than Islam for the next few decades.

Another hope-giving aspect of African Christianity is seeing Africans mature in their Christian faith and theological identity. This is happening now as Africans have become more intentional about doing theology for themselves, for the sake of the African church. This will help African Christianity to be relevant and authentic and to contribute to world Christianity in a meaningful way. It will also encourage African Christians to develop theological resources to cater for their needs and to provide relevant answers to their questions.

Another exciting phenomenon happening is the fact that African Christianity is having an impact globally. African Christians are engaging in mission in the very countries that sent missionaries to Africa less than 100 years ago. They are propping up Christianity in some European cities, for instance, London.

Q. What can Europeans learn from these vital and healthy Christian movements in Africa?

A. African Christians bring to the Body of Christ gifts that, if received, may strengthen it for God's work in the world today. The first of those is prayer which, for Africans, is a way to engage the spiritual world to make God's will happen on earth as it is in heaven. Africans understand this because of the spirit-centred worldview that shapes many African cultures.

So, in addition to engaging the world in prayer, African Christians bring along a theology that includes a robust understanding of the power and work of the Holy Spirit.

Third, African Christians have a healthy understanding of community. They come from cultures that emphasise communal coexistence. Many of us believe that "I am because we are" is the foundation of community life. This speaks volumes when set against the individualistic cultures of the West.

Finally, it is in the continent of Africa that Christianity has truly become a common person’s religion and, because of this, it has the potential of freeing Christianity from the hold of Western middle-class cultures. That way, Western Christianity can learn from Africa how Christianity can respond to the needs of the weak and economically disadvantaged people.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - world - “African Pentecostalism has grown large enough to begin to influence world Christianity”