‘Evangelical cuacuses’ and their influence in Brazilian politics

Candidates supported by megachurches had good results in the local elections. But “many evangelical politicians have been more corrupt than the average”, sociologist Paul Freston explains in an interview.

SAO PAULO · 06 OCTOBER 2016 · 16:57 CET

Several international media agencies have reported in recent months about the growing influence of the so-called “evangelical caucuses”, a number of top politicians who have been propelled to power by some of the biggest evangelical denominations in Brazil.

In the recent local elections, one of the winners was Bishop Marcelo Crivella, a well-known singer who is a member of the neo-Pentecostal group Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (the controversial Universal Church of the Kingdom of God). He will dispute the second round to become mayor of Rio de Janeiro.

But are all evangelical Christians in Brazil voting for the same political candidates? Are those backed by megachurches always an example of honesty and strong values? What can one expect of the relationship between some evangelical churches and power?

“Many evangelical candidates have been more corrupt than the average”, says Paul Freston, a British sociologist who has been living in Brazil for more than three decades and contributes regularly to the Brazilian evangelical magazine Ultimato.

“Forty years ago, it was common to hear non-evangelical people say: Evangelicals are not involved in politics, that is a pity! It would be good that they would be involved more, they would bring good things to the political world. Well, today no one says that.”

Freston teaches in other countries and has written several books, including Religiao e Política, Sim. Igreja e Estado, nao (Religion and Politics, Yes. Church and State, No).

He responded to Evangelical Focus’s questions in the following interview.

Answer. Your first question is easy and your second one is very hard. In the 2010 census, evangelicals as a whole were a 22% of the population. A Pew Forum survey in Latin America in 2014 estimated a 26%, and I think it is a quite reasonable estimate. So, about one in four Brazilians is an evangelical now.

Probably two-thirds are Pentecostals. It is very difficult to say how many would identify with an Evangelical Alliance line. Protestant Liberalism is very small in Brazil, but on the other end of the spectrum you have a large sector of people who are more into a sort of Prosperity Gospel, and they might not identify with the Evangelical Alliance for that reason.

Q. In Brazil there was the impeachment process against former President Dilma Rousseff. Many spoke of the “evangelical pressure”…

A. Well, it is much more complicated than that. You have to understand that there has been a major political involvement of evangelicals since the 1980s, since the return of democracy.

This was largely a phenomenon driven by the large Pentecostal denominations. The Brazilian political system is different from most other countries in Latin America. So, it is possible for these churches to elect their own people to Congress in very large numbers. They have to be a member of a party, but the party is not really important, they are beholden to the church.

So you have what has come to be called in Brazil the Bancadas Evangélicas (in English, ‘evangelical caucuses’). Nowadays they number about 70-80 members, especially in the Lower House of Congress.

That does not mean necessarily that these candidates reflect the political opinions of evangelicals in general but they reflect the ability of these large denominations to mobilise their members to vote for a particular candidate.

Actually, not all of these people have been against the government of Dilma Rousseff or of her predecessor, Lula. For example, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God – which is a large Neo-Pentecostal group – and one large sector of the Assemblies of God – which is the largest denomination in the country - were part of the base of the political coalition that supported the government of the PT, the Workers Party (Rousseff, Lula…) Another large sector of the Assemblies of God and the Foursquare Church were part of the opposition.

In the whole process of the impeachment, the government lost the support of the Congress and also lost the vast majority of the evangelicals in Congress. In fact, the evangelical Congressmen voted for the impeachment at a slightly higher rate than the overall overage, which was already high.

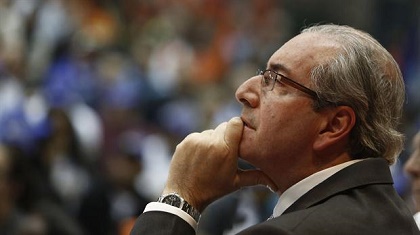

And there was the role of Eduardo Cunha. He was the President of Congress at the time when the impeachment proceedings started. He became the main figure in promoting the process. I suppose we have to call him an ‘evangelical’, he is a phenomenon of this sort of political evangelicalism of the last 20-30 years. He wasn’t really an active evangelical, but became politically important through some evangelical politicians. He worked for an evangelical radio station in Rio and became very well-known and eventually got elected to Congress. So, he is not a man who has a very strong religious background, but he is ‘politically evangelical’, a large part of his political base is evangelical. But at the same time, his reputation is for being extremely corrupt and dangerous. He was removed from the Presidency of the Congress, and has now been removed from the Congress as well. So, he is probably going to face legal proceedings now.

It is because of Cunha’s role that there has been such an emphasis on the role of evangelicals in this business, but the impeachment of Rousseff has not really been a specifically evangelical process. The impeachment would have happened without the evangelicals.

Q. Do most evangelical Christians in Brazil vote for a candidate because of their faith, or would they vote for a candidate based on their lifestyle, their lack of corruption, etc.?

A. Certainly not because for their lack of corruption, because many evangelical politicians have been more corrupt than the average.

In the case of the Pentecostals, most church leaders try to mobilise the vote of their members. They tell them from the pulpit: “You should vote for so and so, who is our candidate”.

Now, that does not work 100%, it never does. Maybe half of the people would follow this, more or less, because many people do not obey the pastor. They would say: ‘I obey the pastor in religious things, but I do not have to obey the pastor in political things’. Other believers would say: ‘I have always voted for this candidate who is not an evangelical, somebody I know, somebody who is from my district’, so it is never 100%. But they [the church leaders] still manage to get enough to elect many of their candidates.

The non-Pentecostals, like the Baptists, the Presbyterians, the Methodists, the Lutherans and so on, they are a completely different thing. Those churches, even if there is somebody of the church who is a candidate, they would not present him or her as the “official candidate” of the church. Why? Because these churches are more middle-class, and middle-class people do not like to be told how to vote. They have more the traditional idea that the vote is secret, the vote is one’s personal decision, and nobody should tell someone how to vote.

There are some Congressmen who are from these churches but their electoral base may be not only from the churches, they usually have some other non-religious base as well. You find evangelical Christians in almost all parties in Brazil across the spectrum. From the left to the centre-left, to the centre, to the centre-right and the right… Except maybe some of the small left-wing parties.

You find evangelical candidates in Federal, State and Municipal elections. The Brazilian political system encourages that. The parties want to maximise the total number of votes they are going to get, so they are usually happy to have some evangelical candidates as well.

Q. How do non-Christians see evangelical politicians in Brazil?

A. Not very well at all. The image is very bad. Forty years ago, it was common to hear non-evangelical people say: Evangelicals are not involved in politics, that is a pity! It would be good if they were involved more, they would bring good things to the political world. Well, today no one says that. The image is very bad.

There are always some evangelical congressmen who have a good image, but the average is very bad. Usually, when people think of ‘evangelical caucus’ they think of corruption, lack of preparedness, they think of people saying stupid things or proposals that would only benefit themselves or the evangelical community. Their fame is very bad now.

Q. Besides politics and the pursuit of power, do evangelical Christians in Brazil believe there are other ways of influencing society for good?

A. First of all, there are evangelicals who believe the involvement in formal politics is important but it should be in a different way from the way it has been done.

Then, you have other people who think that maybe it is more important to act on the level of civil society. Getting involved not so much in elections and parliaments but in civil society organisations, and changing the political culture at a more basic level. Yes, there are many evangelicals who think like that.

Q. What are the topics Christians prioritise when they vote? Besides the usual controversial topics like homosexual unions or abortion, do believers think about other issues like the fight against corruption, poverty, education, care for creation?

A. The reality is that the evangelical politicians have been as corrupt or more than the average. But there is still a very strong evangelical discourse against corruption. Of course no one has a discourse defending corruption. A lot of evangelicals are involved in civil society movements against corruption, and very sincerely.

If you are trying to mobilise a very apolitical community like most evangelicals, something like corruption is an easy way to do it. Everybody understands that corruption is bad and you can condemn it morally. So, you can transfer a sort of traditional religious moral discourse into the political sphere. That does not mean necessarily that you achieve very much, because the reason for corruption in politics are very complex.

And then, yes, of course, there have been the topics of abortion, LGBT movements. But it is not like in the United States, I would say. Because in the US it there a sort of genuine grassroots popular movement about these things. Yes, it is manipulated by the politicians. But in the US it is a genuine grassroots involvement of ordinary evangelicals. In Brazil, not really. You have some tele-evangelists that make a name out of speaking very strongly against homosexuality. It is a selling point, a marketing point for them.

But to what extent this really mobilises people and decides their vote, that is not so clear. Now Brazil has gay marriage.

The abortion law is very restricted, you can only have abortion when there is risk for the mother’s life, in case of rape or when there is anencephaly. So in Brazil there is not a liberal abortion law to fight against. So that does not mobilise people to the same extent as in the US.

And yes, you have a whole sector of evangelicals who would think politically more in terms of issues of justice, especially in an extremely unequal country like Brazil but it is a minority in the evangelical world.

Q. So, what do you think should change so that in the future there are better evangelical political representatives in Brazil?

A. The main thing is the electoral and party system would have to change. But I do not see much hope for this in the short run.

Q. But could nothing happen inside the churches, a broader vision of society, more centrality of the Bible in the preaching that changes the views…?

A. Yes, but that will take decades. The temptations are too strong. The reality is that we are talking about an evangelical community that has become very, very large. It is the largest in the world after the United States. It has become very large very quickly. There is such a big market pressure to have a full church, and you are not going to get a full church by teaching difficult things about politics and ethics. The reality is that is not going to change in the short run.

There are two things which will bring about change at some point in the future, but neither of them will be the work of evangelicals themselves. One would be reforms to the political system: changes in the electoral system and the party system could bring about some changes. The other thing is that, at some point in 20 or 30 years from now, the churches will stop growing. For all sorts of reasons, you cannot keep growing forever. When the growth stops, then you can start to change. Then you will have a communities that are more stable, with more people who are born into the faith. So, in the future, people will want more different types of leadership: people who can teach the Bible in more depth, people who can teach about all the dimensions of discipleship, people who can teach about ethical questions with seriousness… Then things will start to change. But that is not going to happen tomorrow.

The problem is that the image of evangelical politicians will be so bad that it will have a very negative effect on the churches as a whole. I am sorry to be a bit pessimistic. I think there are lots of things that should be done and must be done, but they will probably have a very small effect in terms of the overall situation at the moment.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - world - ‘Evangelical cuacuses’ and their influence in Brazilian politics