After 1984

The Chinese government has begun to develop a social scoring system that will determine people’s ability to travel or access property, amongst other things.

BEIJING · 12 JUNE 2018 · 13:20 CET

For outside observers and judges, the question surrounding control over people’s lives has evolved from a few paranoid proposals into a subtle day-to-day coexistence with technology.

The most famous example of a contemporary dystopia was offered by George Orwell in his novel, 1984, in which he describes a society where an authoritarian government has taken control of all public and private spaces through a system of cameras and microphones.

This idea has been followed by others, such as the first episode of the third season of Black Mirror, entitled “Nosedive”, where class and the possibility of personal development depend on people’s score in the main social network.

A CHINESE SOCIAL CREDIT SYSTEM BY 2020

With the investigation into the publication of private data by Facebook ongoing, the Chinese government has begun to phase in a social scoring system around the country expected to be fully operational by 2020.

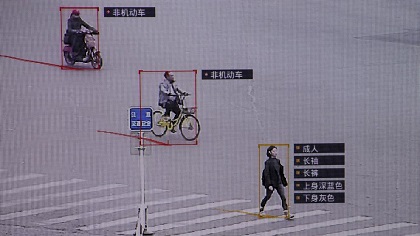

With the help of millions of surveillance cameras installed not only in public spaces, but also places of work and leisure, Xi Jinping’s executive has proposed to look into the attitudes, friendships, contacts, and consumer habits of the Chinese population.

The idea is to establish a scoring system through use of an ID card that will impact on everyday factors such as contracting a higher internet speed, accessing a particular type of housing, or even travel. “In numerous statements the Chinese government has confirmed that the implementation of the social credit system is considered necessary in order to create a culture of trust, honesty and sincerity. This raises two fundamental questions: what kind of behaviours will be punished, and which encouraged? And, who will determine which behaviours are ‘honoured’ or ‘pernicious’? It is a moral issue”, explains psychologist Daniel Sazo, “that has a profound impact on identity and the way that citizens think”.

EVERYTHING COUNTS

Someone who is considered by the authorities to have a negative attitude will be unable to acquire the house that they want, will have no access to certain leisure facilities and will not be able to travel by train or plane. This last measure is one of the first that has begun to be implemented. Basing his argument on Michel Foucault’s references to Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, David Mayo, specialist in the philosophy of science, logic, metaphysics and epistemology, claims that “in a pragmatic sense, such mechanisms can, without doubt, guarantee order and social functioning, but this does not mean that they are ethically advisable or even right. Again, it is important to remember that we are dealing with people who have a natural dignity, not with things or measures”.

Sazo also points to that circular penal structure that, with a tower in the centre, allows uninterrupted serveillance: the Panopticon. “The problem with ‘panopticism’ is that although its objective is to ‘reform’ the individual, the only thing it actually achieves is to make the person give certain responses to particular stimuli. Nothing can be known about their attitudes, their true motivation, or their future actions”, says the pyschologist, who points to a strictly superficial reform. “Through social credit, citizens would do what the government desired of them, but would they really be more honest or sincere?”.

“Perhaps it will help them to be nicer and kinder for a time, but I wonder how long it will last”, considers Rebekah Moffett, a political analyst. “I also question its authenticity. On a social moralistic level, it is far from the grace that we see in the Bible; obviously one cannot demonstrate grace in a natural way if somebody else is forcing you to be nice. I am skeptical”, she states, “because China has tried different controls before, and each one has failed, such as the communes or the ‘danwei’ of the 1950s under Mao”.

POWER, TECHNOLOGY, AND THE CONSEQUENCES FOR THE PEOPLE

In Facebook’s case, it is a dilemma between a lack of government protection and intervention into the market of personal data, or the real inability of governments to establish boundaries to private agents in that sector. With the decision that China has made, the country has become a massive setting that reflects the true relationship between power and technology, and the consequences for the people.

“Once again, the evidence suggests that scientific-technological progress doesn’t imply moral progess. Human beings have used and continue to use intelligence for evil gain”, says Mayo. “We could say that this link between political power and techno-science with its destructive or harmful purposes is an inevitable consequence of historical progression, and it is here where the intervention of ethical reflection becomes very necessary”.

In the same vein as technology being used as a response to conflicts of interest of an established power, Moffett argues that this is the strategy of the Chinese Communist Party to achieve its long-term objectives, and that it is not so different from the ‘birth control’ that prevailed in the country from 1979 to 2015. “I do not believe that it is so far away from Western culture. We already use technology to dictate what advertising we see, or what products we buy. We even use it to influence our vote and political inclinations, as we have seen in the case of Cambridge Analytica. In addition, we are already used to a credit system that scores us as we pay our bills, or if we have taken out a loan, or if we have a mortgage, and this is not so different from having a social credit system”.

Sazo, on the other hand, sees evidence that “social credit could carry with it a high level of stress for its citizens”, and departs from precisely the financial credit system that Moffett refers to. “The pressure that one person can be under from not being able to obtain credit due to a negative bank record can lead to serious problems of anxiety and stress due to the feelings of uncertainty and helplessness that all of this brings. Now imagine the emotional state of someone who cannot even access basic public services or buy a plane ticket because of a negative record on Weibo (the Chinese version of Twitter) or Alibaba”, he says, a situation which, according to the psychologist, could cause long-term consequences for people’s lives.

But even if they were to abolish this social scoring system, “the social stigma for people with psychological issues could be for life”, adds Sazo, who wonders if the system will make exceptions for those suffering from depression or manic-depressive disorders, for example.

NEED FOR CRITICAL AND ETHICAL APPROACHES

Protestante Digital has tried to contact the Christian Study Centre on Chinese Religion and Culture (CSCCRC), but has not received a response. In China, the practice of Christianity is strictly regulated and, in many cases, restricted, thus it remains to be seen how the social ID card will count towards professing a religion distinct from the established one.

For Mayo, it is a consquence of the lack of a critical spirit of reflection on ethics that has led to this point. “It has been said that the causes of the reign of ‘technification’ dehumanising knowledge have been the product of forgetting the great questions” he explains, “or philosophical-scientific questions, that is, the great metaphysicial problems that have and continue to challenge thought on human existence, such as the origin and fate of the universe, or the meaning of existence in its totality, or the meaning of human life”.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - world - After 1984