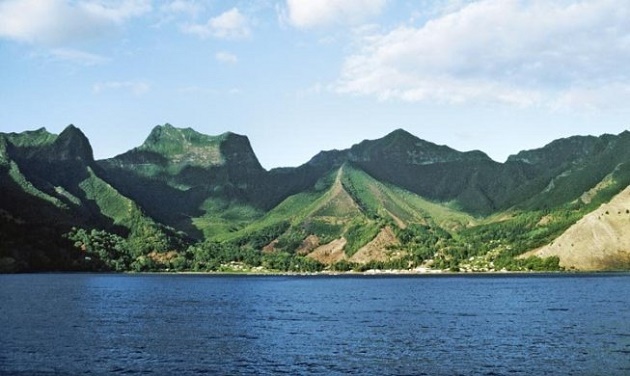

A desert island

Robinson Crusoe does not present historical facts but creates a powerful metaphor that continues to give pause for thought today.

11 DECEMBER 2015 · 11:00 CET

Everyone has, at one point or another, wished him or herself on a desert island. Life is so often stressful that it would be nice to escape to a far-off place and forget about everything around us. That life weariness has made Daniel Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe” (1719), into something more than just another character in literature.

His figure becomes something of a paradigm for humanity, inspiring people from Ridley Scott and the main character in his film “The Martian”, to the Argentinian author Julio Cortázar, who translated the book into Spanish.

Our first encounter with the story relates to that childhood passion produced by the supreme pleasure of adventure. However, reading the book as an adult provides a new perspective on the spiritual meaning of a book that we really knew very little about. It shows us the power of a story that sets man up against the incomparable mystery of God and his providence. The powerful metaphor of this island continues to tell of the reality of the human heart when confronted with the fundamental questions of our existence.

Another Argentinian in exile, Alberto Manguel, says that “you never get to an island without also wanting to leave it”, given that “on dry land, we dream of leaving, sailing over the horizon, landing in a deserted place where we will be able to create the world we want, despotically establishing a little universe”. What happens is that “once on the island, surrounded by cold, hunger, fear, boredom and devastation, all that we ask for is to be rescued”.

The story goes that Chesterton was once asked what book he would take with him to a desert island. The English author, who converted to Christianity, answered with his usual wit: “A Manual on How to Build a Ship”.

THE ROBINSON LEGEND

In 1704, a Scottish sailor called Alexander Selkirk mutinied against the captain of the Cinque Ports and was abandoned on a desert island in the South Pacific in the Juan Fernández Islands, initially known as the Más Afuera (further out to sea) island but later renamed Alejandro Selkirk Island. The sailing master was left with a Bible, a gun and some gun powder and tobacco, but he managed to survive for more than four years, hunting goats and looking out to sea, until he was finally able to return to England in 1711. His story was spread throughout the cafés and pubs in London, where Daniel Defoe must have heard it.

Robinson is not Selkirk, given that his story is mixed up with other tales, such as that of a doctor deported as a slave to Barbados. There are also parallels between Man Friday and an indian who was abandoned on an island by one of the pirates who was seeking refuge during one of his incursions along the coasts and ports of the Vicerroyship of Peru or Chile.

The popularity of the story of Robinson is not based on the presentation of historical facts, but on the creation of a powerful metaphor, that continues to give pause for thought today. It should not be forgotten that this book is an allegory, albeit historical, the meaning of which goes beyond the circumstances experienced by a real person at a given time.

A FOREIGNER IN PARADISE

All the misadventures of Robinson are the result of his apparent obstinacy, being moved by a strange impulse that pushes him towards self-destruction. He does not understand why he runs in its direction, eyes wide open, flouting his clearest perspectives of wellbeing, hurtling towards the deepest abyss of misery. But Robinson comes around one day, when he is shipwrecked by a terrible storm and reaches the “shore on this dismal and unfortunate island”, which he calls the Island of Despair:

“I had hitherto acted upon no religious foundation at all, indeed I had very few notions of religion in my head, or had entertained any sense of any thing that had befallen me, otherwise than as a chance, or, as we lightly say, what pleases god; without so much as enquiring into the end of providence in these things, or his order in governing events in the world”.”

THE ONLY THING THAT CAN CHANGE US

He says that it is as if “a certain stupidity of soul, without desire of good, or conscience of evil, had entirely overwhelmed me, and I was all that the most hardened, unthinking, wicked creature among our common sailors, can be supposed to be, not having the least sense, either of the fear of God in danger, or of thankfulness to God in deliverances.” Given that “through all the variety of miseries that had to this day befallen me, I never had so much as one thought of it being the hand of God, or that it was a just punishment for my sin—my rebellious behaviour against my father—or my present sins, which were great—or so much as a punishment for the general course of my wicked life”.

What made him change his mind? “The grace of God”, writes Robinson. If it had not been for grace, he would have ended “where it began, in a mere common flight of joy, or, as I may say, being glad I was alive, without the least reflection upon the distinguished goodness of the hand which had preserved me”.

THE WORD OF GRACE

On turning to the Bible and reading the words of the Psalm that says: “Call on me in the day of trouble; I will deliver you, and you will honour me”. The Word takes on new meaning “through grace”, whereby: “before I lay down, I did what I never had done in all my life—I kneeled down, and prayed to God to fulfil the promise to me”.

“In the morning”, Robinson says. “I took the Bible; and beginning at the New Testament, I began seriously to read it, and imposed upon myself to read a while every morning and every night;”. And “It was not long after I set seriously to this work till I found my heart more deeply and sincerely affected with the wickedness of my past life.”

He found himself “earnestly begging of God to give me repentance, when it happened providentially, the very day, that, reading the Scripture, I came to these words: “He is exalted a Prince and a Saviour, to give repentance and to give remission…This was the first time I could say, in the true sense of the words, that I prayed in all my life; for now I prayed with a sense of my condition, and a true Scripture view of hope, founded on the encouragement of the Word of God; and from this time, I may say, I began to hope that God would hear me.”

HOW DOES REPENTANCE COME ABOUT?

Robinson continued to live on the island, but he says: “My condition began now to be, though not less miserable as to my way of living, yet much easier to my mind”. He explains this by the fact that: “my thoughts being directed, by a constant reading the Scripture and praying to God, to things of a higher nature, I had a great deal of comfort within, which till now I knew nothing of”.

That is why Robinson says that he gave “humble and hearty thanks that God had been pleased to discover to me that it was possible I might be more happy in this solitary condition than I should have been in the liberty of society, and in all the pleasures of the world”. Accordingly: “though I could not say I thanked God for being there, yet I sincerely gave thanks to God for opening my eyes, by whatever afflicting providences, to see the former condition of my life”.

This is what Christ calls repentance. Something that, as Robinson Crusoe shows us, is only possible through the grace of God. This is difficult to understand, but it has no other explanation than the amazing mercy of God, who takes us to the Island of Despair, to open our eyes and see our lives differently. And this only occurs by “constant study and serious application to the Word of God”. That is how “by the assistance of His grace, I gained a different knowledge from what I had before.”

If you feel shipwrecked in life, open that Word and see things differently.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - A desert island