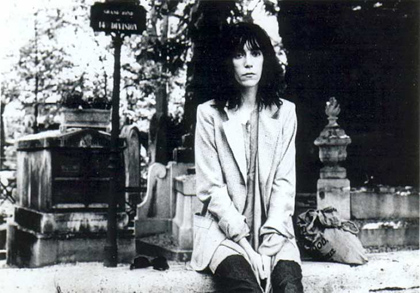

Patti Smith: The childhood dreams of a Jehovah’s Witness

In her famous Album “Easter” (1978), she focuses on the figure of Christ. Back then she said that “the myth of Christ is still exciting and stimulating to me”.

07 MAY 2015 · 11:55 CET

Patti Smith, the legendary singer and visionary poet of New York’s counter culture remembers her childhood as a Jehovah’s Witness in her book Woolgathering. Her previous book, Just Kids, talked about her life at the end of the 60s and beginning of the 70s with the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who died from AIDS in 1989. In contrast, these pages are full of anger. This icon of both the rebellious punk movement and the poetry of the Beat Generation – represented her friend Ginsberg and the pop art of the Andy Warhol Factory –, has always had a strange spirituality, revealing a curious fascination for Jesus.

Patti Smith’s book Just Kids begins: “It was the summer that Coltrane died – referring to the jazz legend who produced the “A Love Supreme” album – The summer of Crystal Ship, the psychedelic song of The Doors. Flower children raised their empty arms and China exploded the H-bomb. Jimi Hendrix set his guitar in flames in Monterey. AM Radio played “Ode to Billie Joel” – the country song by Bobbie Gentry, which is a first person narration about the suicide of a young man set in a gothic southern atmosphere – There were riots in Newark, Milwalkie and Detroit. It was the summer of Elvira Madigan – the Swedish film by Bo Wilderberg, which tells the love story of a tightrope walker and a deserter lieutenant – The summer of love in San Francisco.”

This was still long before Mapplethorpe came out as homosexual and published his photographs of Afro-American nudes, provoking a political crisis in the 1980s in relation to freedom of expression. Robert, “wishing to shed his catholic yoke, delved into another side of the spirit, reigned over by the Angel of Light. The image of Lucifer, the fallen angel, came to eclipse the saints he used in his collages and varnished onto boxes. On one small wooden box, he applied the face of Christ; inside, a Mother and Child with a tiny white rose; and in the inner lid, I was surprised to find the face of the Devil, with his extended tongue.”

JEHOVAH’S WITNESS

Smith was born in Chicago in 1946. Her father read the Bible, but was an atheist, awakening in her a passion for reading, which would lead on to poetry. Her mother was a Jehovah’s witness and would take her children from house to house handing out Watchtower copies. Patti remembers her neighbours threatening them as they shouted at them to go away. She says that her mother taught her to pray, explained that there was an absolute order, and that she could talk to God whenever she wanted to.

The dilemma arose when she tried to choose between her mother’s religious doctrines and her early artistic leanings. “By the time I was about twelve or thirteen I just figured out, well, if that was the trip, and the only way you could get to God was through religion, then I didn’t want him any more”. When she asked the Jehovah’s Witnesses, “Well, what's going to happen with the museums, the Modiglianis, the blue period?” – which she loved so much –, they said that it would fall into the molten sea of hell!”, and she “certainly didn’t want to go to heaven if there was no art in heaven”. However, according to her biographer, her battle with faith became the reason for her artistic vocation as it was through writing, art and music that she would find her own spirituality.

HOTEL CHELSEA

When she was studying art in Philadelphia in the 1960s, Patti Smith read Lorca, listened to the Rolling Stones and acquired her rebellious image. She became pregnant, but gave her son up for adoption. She moved to New York in 1967 to work in a bookshop on Fifth Avenue. She then began living with Mapplethorpe, but when he went to spend some time with his sister in Paris, pursuing the ghost of Rimbaud, he realised that he was homosexual. On his return, she continued living with him at the famous Hotel Chelsea, along with a number of other artists. She began to go to fashionable clubs, to paint, write and act.

Patti was only just twenty when she published her first book, “Seventh Heaven”, but she soon began to brush shoulders with musicians who introduced her to the rock scene in 1971. In 1974 she started her own band and the following year she released her first album, “Horses”. Her most famous collaboration was with Bruce Springsteen. Together they wrote “Because the Night”.

Patti also had an intense relationship with the actor Sam Shepard at the beginning of the 1970s. Together they wrote a play, where the main character announced rock as a new religion which would substitute the Church and its pomp, circumstance and revelation.

ROCK AS RELIGION

“In the old days people had a Jesus and those people to embrace”, says Smith. “They created a god with all their belief energies”. So that “when they didn’t dig themselves they could lose themselves in the Lord”. But “it’s too hard now”, because “God is just too far away”, and “He don’t represent our pain no more”. So “his words don’t shake through us no more”. That is why rock is made “from our own image”. Her band set itself up in the most popular club at that time, which she likened to an evangelical assembly.

The legendary New York musician, John Cale, said that “she had a Welsh Methodist – a Presbyterian denomination born out of the Revival in the eighteenth century – idea of improvisation”. The producer of “Horses” said that her songs were “like declamation…but a lot of Patti’s impulses came from preaching” and prayer. However, the truth is that the studios were full of all the stimulants known to man. Her success rapidly led to a second album, “Radio Ethiopia”, which identified her with the punk movement in England. According to her, above all, the album was “a challenge to God”, to whom she dedicates a whole catalogue of blasphemies. She speaks a lot about Jesus Christ, but through obscenities, in clear provocation.

“Religion is always to the exclusion of other people”, Smith says. “The imagery of religion is fantastic but I can’t get into the dogma.” For her “the one cool thing about music, or the one cool thing about art, is that it’s not to the exclusion of anybody”. And that is why she says that “I think that art and music are the new answers for religion” since “people desperately want to believe in something, but because every time they try to believe in something they’re given a bunch or rules, it doesn’t happen”.

FOR WHOM DID JESUS DIE?

Patti sings that “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine”. She didn’t want “some ethical and mythical symbol taking the blame or the credit for what I do”. In 1977 she suffered from a serious fall which could have left her severely disabled. The accident pushed her towards a deeper mythical quest. The result was her famous album “Easter” (1978), focused on the person of Christ. “The myth of Christ is still exciting and stimulating to me, and whether he's a real guy or not doesn't really matter anymore”.

She said: “I have always sought to communicate with God through myself”, but “in the New Testament man has to communicate with God through Christ”. That is why “I’m reevaluating my state of being, I’m learning to accept a more New Testament kind of communication” and therefore “reevaluate exactly who Christ was”, since “the highest thing an artist goes for is communication with God”

That search did not seem to change her life. For her “the greatest thing about Christ is not necessarily Christ himself but the belief of the people that have kept him alive through the centuries”. It is ultimately a faith in faith. That is the problem. Jesus was nothing more to her than a great man.

But Christ is more than just the path to God. He is God himself made man. And only when we surrender at his feet, we discover that Jesus did not die for somebody’s sins, but for me, so that once I am forgiven, I can speak to Him.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Patti Smith: The childhood dreams of a Jehovah’s Witness