The apathy of ‘Paterson’

We can allow a certain amount of loathing, as the author of Ecclesiastes did, but we must always progress towards hope.

18 APRIL 2024 · 17:00 CET

I have seen few such deep, accurate and sensitive portraits of the mediocrity of ordinary life in the West as some of the films of Jim Jarmusch, and specifically Paterson (2016).

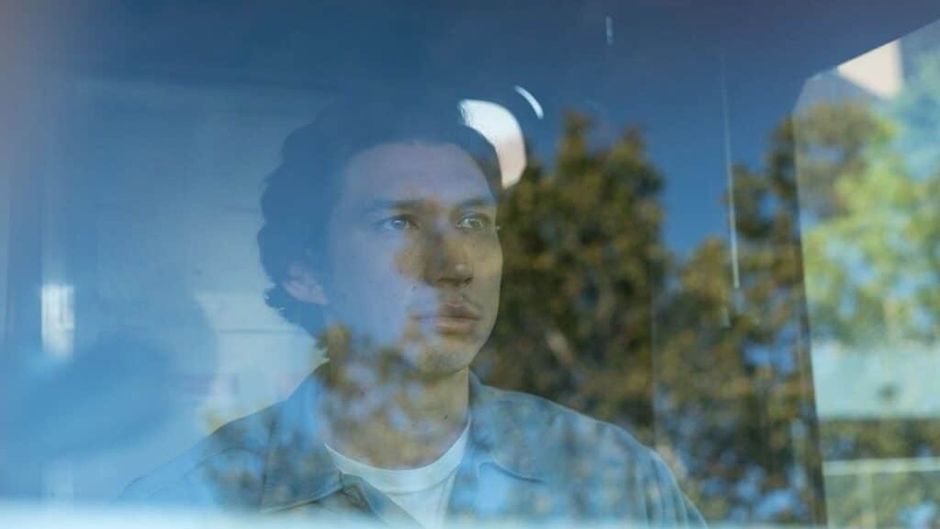

Starring Adam Driver, before he was known for his appearances in Silence, Star Wars or A Marriage Story, the film tells the life of a bus driver, commonly unsatisfied who lives his work, his relationships and also his passion: writing with the usual mediocrity that characterises us.

The film focuses on that strong point that Jarmusch has already explored in other productions, such as Broken Flowers, with Bill Murray: his approach to the monotonous, the everyday and the commonplace.

An example of this tedious daily routine is the coincidence of the name of the protagonist and the city where the story takes place, which is also the name of the film: Paterson.

The way Paterson sits on the sofa reading, his silent way of driving the bus through the streets of Paterson and this existence, driven by habit and contained frustration, was the reason why Jarmusch's film was nominated for the Palme d'Or at Cannes (2016).

Framing the problem

What is really unsettling about Paterson is the appearance of goodness and the profound dissatisfaction with which the protagonist lives: what else could anyone want but a stable, quiet job, in a safe and beautiful city, with a love affair going on and the necessary comforts at hand?

Yet Jarmusch manages to unsettle his audience through his protagonist. It seems that none of that is enough for Paterson, and Driver reflects it perfectly with a general apathy towards life.

It seems that he rather lives a detached love, without any innate, effortless affection.

The same cordiality he shows at his workplace is the one he has for himself in his solitude. It is a quasi-automatic, imperceptible mechanism to get through another day. And the only thing that seems to move his linearity, his writing, literally ends up in the mouth of a dog, to further illustrate the daily frustration.

The usual thing in cinema is the spontaneous, visceral reactions of characters enhanced by some nuance. But the average, mediocre Paterson, with whom anyone can identify, develops an attitude of apathy that makes him simply unperturbed by whatever may happen or happen to him.

The greatness of the Jarmusch film lies in the constant reminder that he doesn't even believe that.

A loathsome whole

In his identification with the protagonist, the spectator also gradually accepts his reluctance, and moves from the understanding to the emotional.

The fact is that, when it comes to evaluate the processes that are repeated over and over again around us, we often confuse exhaustion with disdain.

We may allow a certain amount of loathing, as the author of Ecclesiastes did, but we must always progress towards hope.

The famous preacher said that, after pausing to contemplate and reflect, he “hated life, because the work that is done under the sun was grievous to me. All of it is meaningless, a chasing after the wind” (Ecclesiastes 2:17).

That sincerity, as in Paterson, is to be welcomed amidst so many superfluous stories loaded with too much drama or triumphalism. The problem would be to stay, as happens to the protagonist of Jarmusch's film.

For the author of Ecclesiastes, however, there was hope: “That which is, already has been; that which is to be, already has been; and God seeks what has been driven away” (3:15).

The great event was, and still is, is the Cross and the empty tomb, the death and resurrection of the One who said: “I am the way, the truth and the life” (John 14:6).

Recognising that will not free us from experiencing frustration, but it can give new meaning to our lives, recognising the only One who can restore life, as the preacher in Ecclesiastes said. That is, God.

Jonatan Soriano, journalist in Barcelona, Spain.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Features - The apathy of ‘Paterson’