Christianity in the UK

Church trends in the 21st century.

27 OCTOBER 2021 · 11:50 CET

Although the 21st century is only 20 years old, change is already the hallmark of the UK church scene.

Prior to 2000 the overall assessment of the church was summarized in one word: ‘Declining’. While some would still use that word today, looking below the surface tells a different story.

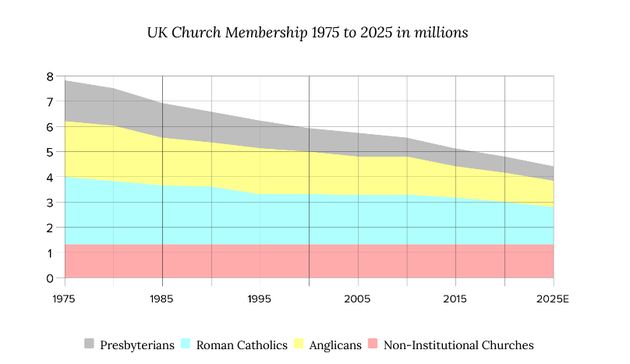

Over the last 50 years, the picture is readily summarized by the following graph, 2025 being estimated:

The overall trend is plain. The Anglicans have seen all their basic measures drop, whether Electoral Roll, Usual Sunday Attendance, or Average Weekly Attendance. In 2012 a new measure was introduced—Worshipping Community—a count of all those associated with a particular church.

While it increased between 2012 and 2015, it has slowly declined since, though it still embraces 1.1 million people, showing the church is actively in touch with 2% of the population.

The Roman Catholic Church has seen its Mass Attendance numbers drop, partly because of the abuse scandals, but also because of a shortage of priests, despite the requirement for them to continue until they are 75.

The Presbyterian Church, largely the Church of Scotland, has seen the greatest rate of decline, partly because some churches have left owing to its changing theology, and other inward tensions.

These three big institutional churches formed three-quarters, 74%, of the total of 6.0 million church members in 2000, almost exactly 10% of the then UK population.

Twenty years later, in 2020, those same three groups formed only 64% of the total, a decrease to 4.8 million, or 7.1% of the population. That shows something of the increase in denominations outside the very large ones.

The three institutional groups have smaller like denominations counted within them. The Anglicans have the Free Church of England, for example, and the newest, the Anglican Mission in England included (with small numbers on its website in 2020 but hoping to have started 250 churches by 2050).

The Roman Catholics started a myriad of overseas chaplaincies (35 in the Diocese of Westminster alone) catering for immigrants from Catholic countries, and there are 15 other smaller Presbyterian denominations included with the Church of Scotland.

The three denominational groups of Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians, including the smaller denominations within each, make up the 64% of total church membership.

However, the total number of all the major and minor denominations in these groups account for only a fifth, 21%, of all the many denominations actually in existence in the UK!

The non-institutional churches

The fourth group in the graph, the non-institutional churches, is, however, very significant. Close inspection shows that it has been growing since about the turn of the century.

There are six denominational groups within it, three declining (Baptists, Methodists, and Independents), and three growing—the Orthodox (which would count as institutional in some countries), the Pentecostals, and the smaller denominations.

The declining denominational groups

Baptists have declined a quarter, 26%, in the 20 years 2000 to 2020 and the Methodists exactly half, 50%. In contrast, the Independents grew between 2000 and 2010 (from 355,000 to 395,000) but have declined again (to 358,000 in 2020), to where they were in 2000.

Why has the earlier Independent growth in this century been lost in more recent years?

This group includes the Congregational churches, the largest of which is Annibynwyr (Union of Welsh Independents), which has seen its numbers halved since 2000 down to 17,500 in 2020.

The Independents also include the Christian Brethren, both groups of which have declined, the Open Brethren by 23% down to 59,000 in 2020, and the Exclusive Brethren by 34% to 13,000.

In addition, the Independents include the many New Churches as they were called, made up of streams like Vineyard, Newfrontiers, Salt and Light, Pioneer, Ichthus, and others.

Between 2000 and 2010 these collectively grew from 46,000 to 69,000, but since have dropped to 61,000, primarily because their church starting initiatives, which had been their major means of growth, stalled.

The three growing denominational groups

First, the Orthodox Churches have had quite a turbulent history in the last 50 years. The largest in the UK, the Greek Orthodox Church, which is four-ninths, 44%, of the total UK Orthodox membership of 480,000, grew between 1975 and 2000, but has been static since.

The Russian Orthodox Church grew very rapidly from 1975 (3,000 in the UK) to 40,000 by 2000, and more than doubled (to 90,000) by 2020.

But with EU legislation allowing Romanians into the UK in 2008, the number has grown from the official Population Census figure of 83,000 Romanians in the UK in 2011 to an estimated 430,000 in 2019.1

The 2020 edition of the World Christian Encyclopedia says 89% of Romanians are Orthodox, and while only a few of these will be active church members while in the UK, numbers are sufficiently great for an estimated 103,000 to be church members, although only about 3% attend church.

All these are part of the Eastern Orthodox churches, in total 90% of all UK Orthodox, the Oriental Orthodox accounting for most of the remainder. While 100 new Orthodox churches have started between 2000 and 2020, their main growth has been in existing congregations becoming larger.

Second, the Pentecostal churches in the UK have exploded in the last 20 years, from 2,500 congregations in 2000 to 4,200 by 2020.

One key observer, however, Dr Joe Alfred, former Multicultural Relations Officer in Churches Together in England, feels there could be literally thousands more uncounted—double the number just given.

The starting of new churches was especially seen in London where 1,000 congregations in 2005 became 1,450 by 2012! Pentecostal church attendance in London in 2012 was 62% of the total Pentecostal attendance in England that year! Many of these are black churches. 2

Church planting has been especially espoused by the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), a major international denomination which began in Nigeria in 1952, and came to the UK in 1993, since when it had started 865 churches by 2020. 3

The RCCG call their churches ‘parishes’, essentially using the same model as the institutional churches—you live near us, why not join us?

The Pentecostal sector, however, is not limited to large denominations like the RCCG (just over 72,000 in attendance), Elim Pentecostal (just under 72,000), and the Assemblies of God (48,000), the three largest, followed by Hillsong (perhaps 17,000), but includes literally hundreds of either totally independent one-off invariably black churches, or very small groups (denominations?) of three or four churches. And they are starting new churches in each of the four UK constituent countries.

There is an enthusiasm, gospel-centred drive, willingness to help and serve in many of these congregations. 4

Third, another large denominational group which is growing is the Smaller Denominations, the largest of which was the Salvation Army, huge in the early 20th century (170,000 members in 1930) but numbering some 31,000 members in 2020, and its weekly attendance of around 25,000 is behind the Seventh-Day Adventists with approximately 38,000.

The group includes the Lutherans (16 small denominations) totalling 34,000, the Quakers (13,000), and the many Diaspora Churches, or Overseas National Churches with 46,000 members in 2020 in total.

The Diaspora include Asian, European, Indian churches, and many others. Collectively it is this group of Smaller Denominational churches which are growing, and the reason is simply (mostly) evangelical churches responding to the needs of floods of immigrants coming into the UK. 5

The growth is seen largely in the expansion of existing congregations rather than the starting of new ones. This catering for those who come from abroad is self-propagating.6

Growing churches

Church growth is also seen where leaders (often ethnically white) are starting new churches in ‘places of need’. Most of these are evangelical. 7

There are many organizations involved in church planting, and many large churches involved in starting or helping to transform existing congregations, like Holy Trinity, Brompton (HTB), which has helped renew over 50 usually city-centre churches. 8

Between 2015 and 2020 some 880 churches were started in the UK, 9 but against this there were 1,900 church closures, of which 540 were Methodist, but closures occurred in every denominational group. Hence why growth is offset by decline.

The post-COVID church

The above describes the church as it was at the beginning of 2020. Lockdown began in March that year, so what of the future post-lockdown? The church as a whole has had to go through a very rapid learning experience, and the curve for some has been very steep.

Many churches have turned to live-streaming, or playing pre-recorded videos of services, whether through Zoom, YouTube, or a host of other like mechanisms.

As journalist Tim Wyatt commented in the March 2021 issue of Christianity, ‘What would have taken us ten years in normal times—catching up with the digital revolution—has happened in a year.’

There have been many reports of people not known to an existing church who have joined in viewing a particular service. 10

Some of these ‘unknown’ viewers will be existing churchgoers trying out a different church rather than new unchurched people. The proportion of the latter is also unknown, but there have been reports of people coming to faith. 11

That will also be augmented by the fact that many older people, and perhaps especially those in Care Homes, will have found the convenience of watching in their own rooms with a cup of tea preferable to travelling to church to sit on a hard seat. 12

On the other hand there will be others, particularly among the elderly, who are not tech-savvy and will be only too glad to come back to real services.

At the time of writing the pandemic has taken the lives of nearly 130,000 people. In 2020 4.9% of the population were going to church. That percentage applied to pandemic deaths means some 6,000 churchgoers will have died. 13

The above comments relate to adults, and projections of their impact on church life post-COVID suggest relatively small losses of those between 20 and 60, but probably much heavier losses (in people not returning) among older people (perhaps 30%).

What of young people? Tim Wyatt says this is an area where many churches have lost out. 14

On the other hand, during lockdown, many churches have engaged in huge amounts of social action, with food banks, counselling services, delivering prescriptions and groceries, staying in touch with the lonely, and so on.

This flourishing of services could lead to new areas of service for local churches, but how far these may lead to evangelism, church attendance, and growth is an unknown scenario.

Church life still has many strengths; churches have taken a battering over recent decades; but post-COVID opportunities lie ahead. Perhaps the word ‘opportunity’ will characterize the coming decade.

Dr Peter Brierley is a statistician, and a former Lausanne Catalyst for Research and Strategic Information. He has been collecting and analysing church statistics for over 50 years and serves now as a church consultant.

This article originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission. To receive this free bimonthly publication from the Lausanne Movement, subscribe online at www.lausanne.org/analysis.

Endnotes

1.Non-British Population in the UK, Office for National Statistics, 2015 to 2019, http://www.ons.gov.uk. ↑

2. Why their growth? ‘Mission is more important than justice’, explained Dionne Gravesande, then of the Afro-Caribbean Evangelical Alliance. ↑

3. This growth has been greatly encouraged by the Head of their UK Executive Council, Pastor Agu Irukwu, leader of the Jesus House for All Nations Church in Brent, London with over 4,000 on a normal Sunday. In 2015 they had 188 churches in London; by 2018 they had 214, according to their website. Their basic aim is to have a church ‘within 5 minutes travel distance’ (by walking or by car) of where people live (in their case, mostly Nigerians). ↑

4. A few have their own buildings, a few meet in their own homes, but the majority either hire a room to meet (often in a local pub) or hire/borrow a local church where they can worship, often led by someone in their 30s or 40s working part-time and pastoring/preaching part-time. ↑

5. Many settle in England, which is why this group is growing in England but not in the UK’s other three countries. ↑

6. If someone comes to the UK to work from, say, Croatia, who struggles with English from Monday to Saturday, they are very likely to go to a Croatian church which speaks Croatian on a Sunday, even if they did not attend church when they lived in Croatia! ↑

7. Some are started by an individual or small group (43%), or are a planned offshoot from an existing congregation (30%), or are an initiative by a denomination (19%) or other ways (8%), quoting the results from the 2012 London Church Census (in a book called Capital Growth). ↑

8. The initial congregation of a newly started (non-HTB) church has on average about 28 people, and often doubles over the first 5 years. Half their leaders are full-time, and the leader of a new church is usually younger than leaders of existing churches (46 years to 54 years). The annual budget initially is about £25,000, or say £1,000 per member. The results of such planting are enormously hard work, but when leaders were asked if they would do it again, 97% said ‘YES’! These churches are across all denominations, including the declining groups. ↑

9. Of which 400 were Pentecostal, 240 Independent, 120 Smaller Denominations, 80 Catholic, 20 Orthodox, 10 Anglican and 10 Presbyterian. ↑

10. These numbers are not widely known but percentages like 20%, 50% or even 100% have appeared in write-ups of services. How long these people actually stay to watch a particular service, or whether they listen to the talk/sermon, is not known. ↑

11. Listening to a service in the comfort of one’s home is far less intimidating than entering a church and a new situation, and some viewers may well prefer to continue to view rather than physically attend. This is therefore an argument for continuing streamed services in some way. ↑

12. They too would prefer to continue with streamed services, even if they miss the companionship and friendship of church fellowship. Whether such is a biblical reaction is another matter! ↑

13. While that is a huge loss, spread across the 45,000 active congregations in 2020 in the UK will mean it will not have a large impact on many congregations, except some of the smaller, elderly congregations found mostly in the countryside. ↑

14. Some with youth workers have managed to provide regular YouTube or video presentations, some churches have run Bible Studies for teenagers over Zoom (‘greatly enjoyed’, said one participant known to the writer), but smaller or middle-sized churches (of which there are thousands) without that kind of support and encouragement may find it very difficult to get their young people back. ‘A large drop-off in adolescents engaging with church would only exacerbate plummeting church attendance figures.’ ↑

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Lausanne Movement - Christianity in the UK