The Grand Inquisitor

Our efforts to gain more influence and power may lead us to execute the very Jesus we hope to announce.

23 DECEMBER 2017 · 17:00 CET

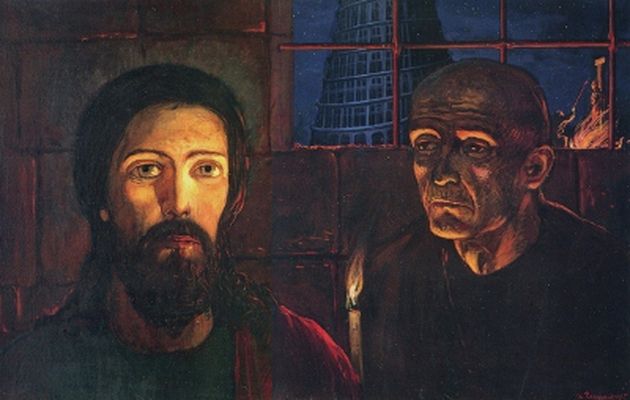

In one of the most electrifying chapters of all of world literature, Russian writer Feodor Dostoevsky imagines an unexpected arrival of Jesus Christ in Seville, Spain, during the height of the Holy Inquisition.[1]

Jesus enters the city unannounced, silently, but people recognize him immediately. People gather around him, amazed, and Jesus,with a smile of compassion, walks across down the crowd, irradiating love. He extends his hands over their heads and blesses them, and those who touch his clothes receive power and healing.

A man blind since his birth shouts, “Lord, heal me, that I may see you”, and the scales fall from his eyes and the man begins to see. The crowd weeps for joy and kisses the ground on which Jesus walks, and children lay flowers on his path and sing “Hosanna.”

Jesus stops in front of the cathedral, where a white coffin is being carried, amidst weeping and wailing, with the body of a girl covered with flowers. “He will bring the child to life!”, shouts the crowd, and when the coffin rests at Jesus’s feet, the crowd sees the girl get up with a flower in her hand.

People are moved, ecstatic, but suddenly the door of the cathedral opens. The Cardinal comes down the stairs, a tall man in his nineties, with sunken eyes and a wrinkled face, the Cardinal who heads the Inquisition.

He stops in front of the crowd, and observes. He saw it all – the coffin, the little girl, the commotion – and raises his hand and orders that Jesus be arrested.

The hot summer evening arrives, and we see the Cardinal open the iron door of the cell, carrying a lantern and saying, “Why should you come now, to hinder us in our work? ”

The monologue that follows is stirring – only the cardinal speaks, Jesus remains silent – and the Cardinal remembers when Jesus was tempted by Satan in the desert. He rejected the three greatest powers at its disposal: the miracle (turning stones into bread), the power of spectacle (throwing himself from the temple to be saved by an angel) and dominion over all kingdoms on earth.

Respecting human freedom, Jesus became too easy to be rejected, and missed his biggest advantage: the power to impose faith. Fortunately the church has recognized Jesus’ mistake, says the Inquisitor, and relies on the miracle, performance and power from then on, and for this the Inquisitor must burn Jesus on the stake, lest he disturbs the work of the Church.

It is a thrilling chapter, enough to send chills up our existential spines. What is Dostoevsky up to here? For those of us who do not believe, he asks us to separate what we understand of “Church” from what we understand of “Jesus.”

Actually, in Dostoevsy’s scenario, the Church may negate much of what Jesus affirmed in its quest for power, prestige and wealth.

Like the surprising ending of Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, choosing the cup of gold and diamonds – seemingly the cup of a King – leads to death, as we overlook the humility and divine humour in the offer of eternal salvation coming from a young peasant executed like a criminal.

So many of the friends I have and the people I know don’t give Jesus a hearing because of the sins and scars of Christians, and Dostoevsky invites us to deconstruct this easy association and to see that there is more in Jesus than the worst examples of the Church.

For those of us who are Christians, however, especially those who are leaders in some capacity, I hear from Dostoevsky a profound call to repentance and humility.

It is scary to think that our efforts to gain more influence and power may lead us to execute the very Jesus we hope to announce.

It is shocking to imagine Jesus dying on the cross with the full weight of the sins of the world on him, and yet have us crawling on top of him – “look at this Jesus,” we say – as a vantage point for our ambition and renown.

Let us not forget the radical humility and powerlessness of the Jesus we follow, and emulate it ourselves. This humility may be the very feature that makes people look for Christ again and the key to influence we hope to have.

[1] Feodor Dostoevsky, “The Grand Inquisitor”, in The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Farrar, Straus ad Giroux, 2002), 246-264.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Culture Making - The Grand Inquisitor