‘Only the Dead’, religion makes people angry

“We need to acknowledge this darkness within the human soul because only by coming to some understanding of it can we ever truly hope to embrace the light”, says war correspondant Michael Ware.

12 FEBRUARY 2016 · 13:18 CET

War correspondent Michael Ware talks to Solas Magazine reviewer Mark Hadley about his new documentary that details his descent into the darkness that is al Qaeda and Daesh (IS).

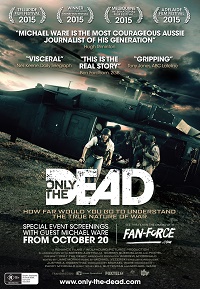

He is as Australian as they come and during our interview I get a sense of the “down under” jocularity that must have helped carry Michael Ware through the worst horrors the Middle East has to offer. After more than seven years as a war correspondent and bureau chief living in Iraq, Ware has decided to release a documentary on the dark heart of the Middle East called Only The Dead. However, he freely admits that he is as much a part of its story as the terrorists he chronicles.

“In one sense this story takes place in the pre-history of what we now call the Islamic State,” Ware relates over the phone. “But the focus of the narrative are my dealings with the man who created the Islamic State and what my pursuit of him not only revealed about the war itself, but what it revealed about me.”

Ware’s experience is hard to overrate. He began his war correspondent years reporting on the Indonesian invasion of East Timor for Time magazine in 2000, before transferring to Afghanistan to follow the United States hunt for al Qaeda. From 2003 onwards, he followed American troops right into the heart of Baghdad with the onset of the Iraq War. There, he began reporting for CNN as well as becoming Time’s Baghdad bureau chief.

Ware is one of the few mainstream reporters to live in Iraq near-continuously since before the American invasion, so it’s not surprising he also worked hard to cultivate contacts with Kurdish fighters and the Iraqi insurgency. This, he says, exposed him to a type of virulent religion that even then he realised would have far-reaching implications. “It was like being able to see our future unfold right then and there in front of me,” he tells me. “I could see from what was going on around me that this kind of militant Islam was going to keep impacting upon us, not just in that region but around the world for generations to come.”

Only The Dead is pieced together from the horrors Ware witnessed and filmed during those times, though it doesn’t aim to pass judgment on the conflict itself or even most of the combatants. First and foremost it is an examination of Ware’s own descent into the evil he was reporting on. His profession leads him to become a bloodhound for bad news. As the Gulf War and insurgency years unfold on screen, we witness his relationship with Islamic fighters deepen until he eventually becomes a go-between for the infamous al Qaeda terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and his horrific media campaign. The result is not only a terrifying revelation of the barbarous acts taking place but the transformation of the very normal people caught up in them, including the narrator: “I felt [Zarqawi] had made me complicit somehow in his war. [But] if he was obscene, the dark idea of him was becoming perverse.”

Only The Dead is both riveting and revolting; a film that should be viewed with extreme caution, but viewed nonetheless. The European community continues to reel from the consequences of an ongoing conflict that has displaced millions, recruited the vulnerable to participate in horrific acts and given rise to stunning human rights abuses. In that respect, Only The Dead’s disturbing images have little new to offer. Terrorist and news organisations alike have already colonised the internet with equally disturbing pictures. However, what Ware offers is a spiritual dimension on the conflict that is barely mentioned in the mainstream media.

Thinking back on the daily exposure to death and mayhem, Ware says it’s extraordinary what one can become accustomed to. War became his norm. “I found a hidden darkness lurking in my soul that I never knew I had, and that’s what we hope is the broader conversation that comes out of this film,” he says. “This is an opportunity for all of us to look at that human condition, that light and that dark that dwells inside each and every one of us.”

Ware uses the thought to reflect on humanity’s seeming inability to leave violence behind. His narration wonders whether we will ever be able to move beyond the sort of inhumanity that characterised the Taliban, al Qaeda and now the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). It’s not just the perpetrators or the victims who are transformed by such extreme violence, but those who report on it, and even we who watch it. Ware contemplates his years of concentrating on Zarqawi and concludes the terrorist’s atrocities wore away at his soul, reducing his essential humanity: “Zarqawi’s men kept on fighting, the dark idea he had unleashed too powerful to contain. He showed us recesses in our hearts we didn’t know we had. I was just so twisted up inside. At some dark hour I became a man I never thought I’d be.”

Ware reached this conclusion when he found himself filming the slow death of an Iraqi insurgent who had been wounded by US Marines. His unrelenting camera work testifies more than his words how unconcerned he had become. With intense sincerity he tells me on the telephone: “We need to acknowledge this darkness within the human soul because only by coming to some understanding of it can we ever truly hope to embrace the light.” As a Christian I can’t help but agree. Jesus would have said only those who know they are sick welcome the doctor. But Ware’s experience with al Qaeda has also left him with a distinct conviction about where the root of the documentary’s darkness lies.

“One of the greatest killers in the world is T.B. – true believers,” he tells me. “It’s not Islam that has a problem, it’s absolutism. Anyone who believes so firmly in the righteousness of their own ideas that no new information or evidence can change that blinkered view …” his voice trails off, his frustration evident. “These are people you cannot negotiate with.”

Ware is not the first person to point to fundamentalists as the authors of some of history’s darkest chapters. Look beyond the Iraq War to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Europe’s Thirty Years War, the Crusades … and you can start to see why some people think religion in particular makes people angry. As Christians we might instinctively rise to defend the charge by pointing to the many good things believers have done in God’s name. However, we’d do well to consider that religion was the primary motivation for the zealots who opposed Jesus.

In the Gospel of Mark, the Pharisees come into conflict with Jesus over a number of specifically religious questions like fasting and forgiveness, with the flashpoint becoming appropriate behaviour on the Sabbath. Jesus heals a man with a shrivelled hand, telling the Pharisees the laws they were obsessing over were supposed to reflect the character of God, not become gods in themselves. “Which is lawful on the Sabbath,” he asks them, “to do good or to do evil, to save life or to kill?” But they will not answer because they are more dedicated to their rules for worship than the mercy of God. In fact, Jesus’ refusal to submit to their religion raises in them a level of anger that rises to murder: “Then the Pharisees went out and began to plot with the Herodians how they might kill Jesus” (Mark 3:6 NIV).

Only The Dead makes it abundantly clear that the association between offended religion and murderous rage is still very much with us. Ware narrates that Zarqawi’s worst atrocities were perpetrated in the name of laying what would become the foundations of ISIL. Yet we don’t have to go to Syria to discover offended religion resulting in anger. A friend of mine was recently conducting a Christmas service at his church where he had the opportunity to preach the Gospel to hundreds of non-Christians. Afterwards, he was returning to the vestry thanking God for the opportunity, when he came across a group of deeply upset women from the church. They were angry to the point of tears because a few verses had been left off the reading of a traditional passage of scripture.

Ware suggests that any religion – Islamic, Christian or otherwise – that is so closed it cannot listen to reason is a dangerous belief system. Jesus would agree. The fundamentalists of his day missed the Saviour of the world because they could not see beyond teachings taught by men.

When we elevate our practises above what God actually requires of us, we not only risk destroying ourselves, we invite the sort of self-righteousness that eventually saw Jesus nailed to a cross. Only The Dead is a tale we should certainly take caution from. Religion that is unfettered from grace is indeed a real danger, for ISIL, the secular West and for us.

Mark Hadley

This article was first published in Solas magazine. Solas is published quarterly in the U.K. Click here to learn more or subscribe.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Solas - ‘Only the Dead’, religion makes people angry