Tolkien film at last in Europe

The main thing that J.R.R. Tolkien inherited from his mother was the Roman Catholic faith. With the help of a priest, he was able to gain access to higher education.

08 JULY 2019 · 11:00 CET

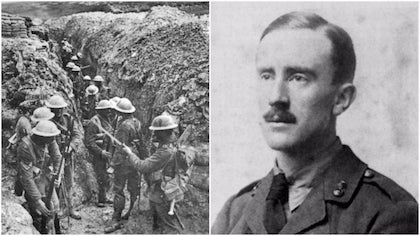

In June, the Tolkien film that came out two years ago at last premiered in Spain. The delay occurred in the United States, where the producer was bought by Disney – the Finnish director Dome Karukosko originally worked with an independent division of Fox Searchlight –.

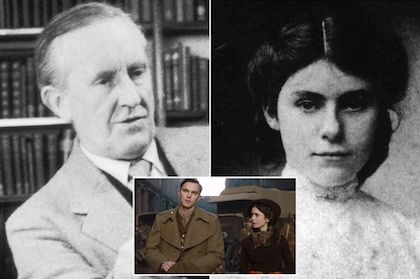

The film provides a discrete glimpse into the childhood and youth of the author of The Lord of the Rings, his faith, the trauma of the First World War and his love story with his wife Edith.

Although there are a number of Tolkien biographies – including the classic by Humphrey Carpenter – the best, I think, is possibly the one by Michael White. In amongst a growing bibliography on the author, we also find Hispanic contributions, such as Daniel Grotta and Eduardo Segura’s (the latter a PhD in English Literature and one of the advisers to the Director Peter Jackson).

Interestingly, the official book of the making of the second film in the trilogy is written by an evangelical Christian, Brian Sibley, who has also written various books about Tolkien’s Anglican friend, C. S. Lewis. There are, in addition, a number of noteworthy essays about the influence of Roman Catholicism in Tolkien’s work, such as Joseph Pearce’s Tolkien: Man and Myth.

White is a professional biographer who has written about characters as diverse as Mozart, Asimov and Lennon, but above all, about important scientific figure such as Leonardo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein, Galileo and Hawking. He isn’t one of those Tolkien specialists who knows the names of all the dwarf kings and elf princes. But, in that, I think that he is like most of us. One thing is to like Tolkien, as in White’s case, and another is the fanaticism of academics, who are capable of boring the socks off the most enthusiastic of readers with maps, songs, chronologies and genealogies of Middle Earth. From that perspective, I think that White provides an excellent introduction to Tolkien’s life.

THE NOSTALGIA OF ORPHANS

Born in 1892, Tolkien was baptized John Ronald Reuel in the Anglican cathedral of Bloemfontein, in South Africa, where his father was the director of a Bank. His mother’s poor health and constant frustrations took them back to England, leaving his father in Africa, where he died suddenly, shortly after Tolkien’s fourth birthday. His mother thus became the main influence in his life. He spent his best years with her, living in the countryside, playing in the woods and reading fantastical stories about dragons, serving as great inspiration for his own work. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis shared a constant nostalgia for childhood that made them both feel like spiritual orphans.

The main thing that Tolkien inherited from his mother, however, was his Catholic faith. When she converted to the Roman Catholic Church, her whole family rejected her. Her father was a strict Methodist, who became a Unitarian towards the end of his life, and he refused to have any contact with her from that point onwards. Her brother-in-law was a major figure in the Anglican Church in Birmingham. He had been the one to provide for her financially when she went back to England; now he withdrew all help, leaving her in the arms of Catholic charity. It is, therefore, no surprise that Tolkien hated Protestantism, which he always considered as his enemy, a feeling that was only intensified when his mother’s diabetes worsened and she died at the age of 34. Tolkien always saw her as a martyr to her faith.

Tolkien’s Roman Catholicism is therefore not any old kind of Catholicism. It is a faith of conversion. The proof is that Tolkien found his spiritual home – as so many other contemporaries, including Chesterton, Greene and Waugh – in the oratories founded by Newman, who went from being an Anglican minister to a cardinal in Rome. Tolkien’s tutor was a priest at the Birmingham Oratory who helped his mother when she was left to her own devices: father Francisco Javier Morgan. With his help, he was able to gain access to higher education, learn a number of languages and developed a love for the “blessed sacrament”.

His faith was so sacred that it somehow always lay beyond all his fantasies. This is one of the mysteries about Tolkien: how such a proselytist Catholic was able to resist the temptation of making his work an allegory of faith. This was one of the greatest differences between him and Lewis, who in a certain sense sacrificed his literary reputation to dedicate his life to producing an apology for Christianity in an academic environment that ridiculed him.

FRIENDSHIP AND CONVERSION OF LEWIS

Tolkien and Lewis met as English lecturers at Oxford. They shared some of the most creative years of their lives. Together they created the Inklings, a literary discussion group which used to meet in Lewis’ university rooms and at the Eagle and Child pub in Oxford. If you go to the pub today you will find photographs of their group and a commemorative plaque –it was where Tolkien first read The Lord of the Rings, and where Lewis first spoke about Narnia and The Screwtape Letters.

Their meetings became fewer and further between after the start of the First World War, a period over which Tolkien and Lewis grew apart. Their relationship definitively cooled off in the 1950s, even though the Inklings carried on until just before Lewis’ death in 1963. What happened to them?

White dedicates a whole chapter to the friendship between Tolkien and Lewis. There was no one that Tolkien opened up to as much as Lewis, accepting many of his suggestions and asking him to be the first to read The Hobbit. Tolkien’s feelings towards Lewis were so intense that he could not bear the intrusion of a third person when a writer called Charles Williams arrived in Oxford and absorbed Lewis’ attention. He was older than both of them and had already written twenty-seven books. He had worked at the Oxford University Press after having to leave his studies due to his father’s financial problems. Lewis not only brought him along to his meetings with Tolkien, but he also fought hard to get him a position at the university, even though his degree was only honorary. This made Tolkien jealous, feeling that Lewis had replaced him as he became an increasingly successful author, while Tolkien remained unknown.

Lewis had grown up in a Protestant environment in Northern Ireland, but he considered himself an agnostic when he met Tolkien at the age of 20. For him, Christianity was a myth like any other, which is why he was surprised to meet someone intelligent like Tolkien with such a commitment to his Catholic faith. Their friendship gave him another perspective on God, which in 1931, following a famous conversation, led him to think that the myth of Christ might in fact be true.

Lewis’ conversion made Tolkien hope that he would become a Catholic like him. Instead, though, Lewis returned to his Protestant roots. What’s more, he became an apologist for a faith in which Tolkien thought he had not yet gained enough maturity, writing about his conversion in The pilgrim’s regress (1933). Lewis dedicated his Screwtape Letters to Tolkien even though the latter didn’t really appreciate any of his books. He himself worked slowly and meticulously and found Lewis’ work too rushed and superficial.

DIFFERENCES WITH LEWIS

Tolkien’s work is generally considered to be children’s fiction, but whoever has read his stories gets a feel for his attention detail. The names are well thought out, although the majority are taken from the Edda of Icelandic mythology. He was continually revising his writing and driving his editors to distraction. He was so obsessively insecure in his corrections that he had to rewrite each book out time and again. He was moreover never able to meet any of his publication deadlines. For example, he started to edit three classical English poems in the 1930s, only to finish them in the 1960s. In the end, the preface had to be written by his son Christopher, who was actually responsible for bringing most of his father’s work to light posthumously. Lewis, on the other hand, had been churning books out since the 1940s, in addition to contributing to many joint publications, giving conferences, classes and even radio talks. This not only explains their difference in popularity, but also in income. Time seems to have given Tolkien the upper hand, however.

Contrary to most biographies about Tolkien, White appears sympathetic towards Lewis although he attributes a certain liberal sexual conduct to him that is not clearly demonstrated. It is true that as a bachelor Lewis lived in the same house as his brother and a divorcée, Janie Moore, the mother of one of his army friends whom he had promised to care for until her death. But the age difference between them suggests that there was something more of a maternal rather than sexual relationship between them.

THE BREAK

The breaking point for Tolkien came when Lewis met another divorcée, Joy Gresham, an American Jew who had also converted to Christianity. As she lived with Lewis some time before getting married, together with the two children that she had had with an alcoholic Hollywood writer who had been constantly unfaithful to her, White supposes that that relationship was also sexual. I do not think that it was, although there is little ground to reach the extremes of his secretary Walter Hooper, who claims that they lived a celibate relationship even after they married due to her illness from cancer. At that point Hooper had become an episcopal minister, after which he converted to Roman Catholicism and now he even hopes that Lewis will one day be canonized!

Although Tolkien’s love story, as recounted in the film, was with his wife Edith, Lewis’ marriage to a divorcée pushed him to break with him. Joy was very independent, a writer, and a Presbyterian to boot. Interestingly, she became friends with Edith, who always regretted having to convert to Catholicism in order to marry Tolkien. White describes their marriage as somewhat cold and distant as he seemed to prefer the company of friends and his children to that of his wife’s. This could just be more speculation though.

However, after Joy’s death in 1960, immortalized in the film “Shadowlands”, Tolkien and Lewis never met again. And when Lewis died in 1963, Tolkien refused all invitations to talk about him, even though Lewis had always talked and written enthusiastically about Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings. Thus ended a long friendship that had brought together a circle of writers who would make literary history.

REFLECTIONS OF GRACE

That club in Oxford did more than just smoke pipes and drink beer. Their conversations inspired great pieces of literature that continue to attract the modern reader and spectator. Their subjects should, at the end of the day, interest everyone.

In Tolkien’s work, we see the power of evil represented by Mordor, the temptation of sin in the ring, the miracle of forgiveness and the sacrificial love of the characters: this all speaks to us of the reality of redemption beyond myth. Its exaltation of nobility, integrity, trust and faithfulness continue to strike a chord in a desperate world.

In that regard, Tolkien’s work awakens in our deteriorated spirit a thirst for goodness and for the glory of the Lion of Judah, in the same way as the figure of the lion Aslan in Narnia reminds us of the Lamb on his throne, holding all power over heaven and earth. These aren’t parables, but reflections of the grace that belongs to those who – hobbit-like – are gentle and humble in heart and who will one day inherit the earth.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Between the Lines - Tolkien film at last in Europe