The Gospel of Judas: what it says, why it is not credible

What about the gospels not included in the Bible? Why were they not chosen? What do they say?

29 JULY 2017 · 17:00 CET

When talking about Christianity and its historical origins with people, I have been asked by many: what about the gospels not included in the Bible?

Why were they not chosen? What do they say? Is there some kind of conspiracy going on which chose “the official truth” and left out legitimate voices?

This month I read N.T. Wright’s commanding study[i] of maybe the most talked-about alternative gospel: the Gospel of Judas. It is a fascinating read. But for those of you who can dedicate only 6 minutes and 43 seconds to the topic, here’s the skinny.

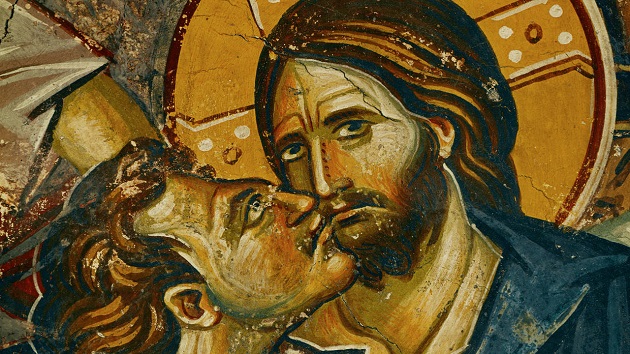

What it says: The Gospel of Judas is essentially a dialogue between Jesus and Judas, where Jesus asks Judas to hand him to death, and Judas obeys the command. Judas is the hero who helps Jesus escape this corrupt world by handing him over to death. Its worldview is quite different from the canonical gospels written by eye-witnesses or friends of eyewitnesses of Jesus. It features an obscure cosmology of heavenly realms and the idea that people have a “native star” that echoes the cosmology of Plato. Here a flavor:

“Adamas was in the first luminous cloud that no angel has ever seen among all those called ‘God.’ He … that … the image … and after the likeness of [this] angel. He made the incorruptible [generation] of Seth appear … the twelve … the twenty-four … He made seventy-two luminaries appear in the incorruptible generation, in accordance with the will of the Spirit. The seventy-two luminaries themselves made three hundred sixty luminaries appear in the incorruptible generation, in accordance with the will of the Spirit, that their number should be five for each.” (58-59)

Where it came from: The Gospel of Judas and most of the alternative gospels are products of a 2nd and 3rd-century (con)fusion of Christianity and Greco-Roman spirituality called Gnosticism. Wright describes its four main tenets as:

(a) “a deep and dark dualism” which makes this world essentially bad “and a place which, had it not been for an evil god going ahead and creating it, would not have existed at all”;

(b) the creator god is bad and corrupt but “there is another divine being, a pure, wise and true divinity”;

(c) salvation means “to escape the wicked world … attaining deliverance from the material cosmos and all that it means”; and

(d) “the way to this ‘salvation’ is precisely through knowledge, ‘gnosis’.” (pp. 31-33)

So, more than Savior, Jesus is a revealer whose secret collection of sayings imparts this enlightening knowledge. The gist of the story according to the Gnostics is “the story of a higher god who trumps the wicked, world-creating god of Israel and enables some humans, led by a mysterious revealer-figure, to discover the true divine light within themselves and so be liberated from the created order, and the created physical body, and all the concerns that go with the material world.” (71)

Why it is not credible: The Gospel of Judas is of course a credible historical artifact of 2nd and 3rd-century Gnosticism and its Christianity-borrowing wing. Yet, if our question is the historical origins of Christianity itself and the real Jesus who lived in Palestine, the Gospel of Judas does not contain credible information for a few reasons.

1. Date: It comes much later than the gospels written by the eye-witnesses. The Gospels in the Bible were written between 60 and 100 A.D. Our copy of the Gospel of Judas, on the other hand, was written between 240 and 320 A.D. in a local variation of Coptic (23-24). We have thousands of manuscripts of books of the New Testament, some going back to the 2nd-century, but just one late manuscript of the Gospel of Judas.

2. Recognition: The Gospel of Judas was not recognized (or even known before it existed of course) by the communities of early followers of Jesus, who instead recognized pretty unanimously the biographies written by Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John. When the canon of the New Testament was selected, there was debate about whether to include the books that now are at the end of the New Testament, such as 2 Peter and Revelation, but unanimity regarding the four gospels. No one then considered alternative gospels written centuries later by unknown authors (who used nonetheless names of apostles) as credible as the first biographies.

3. Cultural distance: Its message conforms to the wider 2nd and 3rd-century Greco-Roman context and is utterly foreign to 1st-century Palestinian Judaism. In fact, describes Wright, “One key feature of all such texts is their relentless hostility to the main lines of ancient Judaism”. The world is not good (unlike in Genesis); the creator is a malevolent god; the climax of salvation is not resurrection and a renewed world but escape from the world. Therefore, it is historically not credible to consider the Gospel of Judas a true expression of the teachings of Jesus when it contradicts the teachings recorded by the eye-witnesses and the Jewish roots of that worldview. It is totally credible, however, to consider the Gospel of Judas an expression of 2nd and 3rd-century Gnosticism who uses the name of Jesus to voice their message.

“Keep Jesus as the key figure, a great and powerful teacher, one who has come from the other side to tell us that it’s about and to rescue us from our plight… and simply adjust the nature of the plight (no longer sin, but materiality), the picture of God (no longer the creator of the material world, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, but a distant, pure being, unsullied by contact with the creation), the nature of salvation (no longer God’s kingdom and justice coming to birth within the space-time universe, but instead the rescue of some humans from the material world altogether) … and, lo and behold, we are still followers of someone we call ‘Jesus,’ but now we have a worldview and a religion without those nasty Jewish bits.” (39)

Verdict: Is the Gospel of Judas, then, a credibly recorded and transmitted dialogue between the historical Jesus and the historical Judas who lived in Palestine? Wright, a usually nuanced and sophisticated theologian, arrives at a quite clear conclusion: “In other words, anyone knowing the relevant history must realize that there is no chance of the ‘Gospel of Judas’ giving us access to the genuine, historical figure of Jesus of Nazareth.” (64) In a similar way, James M. Robinson, quoted in Newsweek, affirms that the Gospel of Judas “tells us nothing about the historical Jesus and nothing about the historical Judas. It tells only what, 100 years later, Gnostic were doing with the story they found in the canonical Gospels.”(64) Francis Spufford arrives at a similar conclusion, talking about not just the Gospel of Judas but most gnostic gospels:

What these other ‘gospels’ are instead is a series of pamphlets in which Jesus serves as the mouthpiece for the author’s preoccupations, usually magical or esoteric. It isn’t that they cast an intriguingly different light on someone who is recognizably the same person as the one in the New Testament. They are worlds away in mood and tone and attitude… Read much of the rival ‘gospels’, and you start to think that the Church Fathers who decided what went into the New Testament had one of the easiest editorial jobs on record. It wasn’t a question of suppression or exclusion, so much as of seeing what did and didn’t belong inside the bounds of a basically coherent story. [ii]

Quite a clear conclusion to me: just slightly more historically credible than Lady Gaga’s spin-off of Judas.

[i] N. T. Wright, Judas and the Gospel of Jesus: Have We Missed the Truth about Christianity? (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2006).

[ii] Francis Spufford, Unapologetic: Why, despite everything, Christianity can still make surprising emotional sense (London: Faber and Faber, 2012), 155-156.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - Culture Making - The Gospel of Judas: what it says, why it is not credible