“Our culture of selfism is producing more narcissism and fragility”

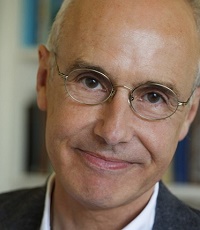

“We need a realistic, grounded sense of self that is not pre-occupied with maintaining its own importance, but serving a purpose bigger than ‘me’”, says Psychiatrist Glynn Harrison, author of ‘The Big Ego Trip’.

14 DECEMBER 2016 · 12:33 CET

Some of the main influencers in the world at the moment are ‘youtubers’ and Instagram stars. Admired and followed by millions, they constantly work on growing their personal brand.

A strong “ego” seems to be the key for this kind of success: to know what your dreams are and to believe in yourself enough to achieve them.

But where does this self-centred worldview come from? And how does it contrast with what the Gospel says about personal success?

In his book The Big Ego Trip, Psychiatrist Glynn Harrison analyses the roots of the self-esteem movement and some of the tangible consequences it has had.

The former Professor and Head of Department of Psychiatry of the University of Bristol (UK) believes Christians often fall in the same unhelpful trends: “many churches are tempted to air-brush the call to ‘die to self’ that sits at the heart of the Gospel”.

Glynn Harrison responded to questions of Evangelical Focus in the following interview.

A. It depends what he meant by ‘ego’. But yes, excessive self-belief and an inflated sense of your own importance does create a drive to succeed. It works the other way around, however. People with a low sense of self-worth may also be driven to succeed because they are fighting to prove their worth.

Both extremes can cause stress, or problems such as narcissism, as I show in my book. In the end we need a realistic, grounded sense of self that isn’t pre-occupied with maintaining its own importance, but serving a purpose bigger than ‘me’.

Q. You say “boosterism” does not work. How would you define this trend in the field of education? Why is it failing to build a better society?

A. ‘Boosterism’ is talking up somebodies abilities and qualities in ways that have no relationship with reality: ‘you’re special!’ ‘You’re a star!’ It’s usually done with the right intentions - we want people to be confident and to flourish – but it creates a pre-occupation with ourselves and centres motivation around maintaining self-importance.

Psychologists have shown that kids ‘boosted’ like this tend to avoid difficult tasks that put their self-image at risk. Children need to be resilient learners who want to know everything about the world and make a difference.

Q. Another idea that comes out of your book is the idea that we are creating a society of frustrated people. How have we come to this point?

A. Because we are raising unrealistic expectations. When we over-boost our children in an attempt to raise self-esteem, we create a generation of self-absorbed youngsters who measure their worth in terms of success and celebrity.

It would be better to nurture resilient, outward-looking kids with a sense of their own uniqueness and individuality – not narcissists pre-occupied with their social celebrity and importance.

A. We’ll have to see. Most pendulums eventually swing back. More and more people are recognising that our culture of selfism is producing more narcissism and fragility.

The obsession with ‘safe spaces’ and identity politics on campuses appears to be the latest manifestation of the need that self-orientated people have to protect their fragile ego’s. But as more educationalists cotton on to the dangers, schools are beginning to talking more about building character and resilience rather than boosting self-esteem.

Q. Are churches falling into the cultural trend of sending wrong messages that only revolve around the felt needs of people?

A. Yes, I think they sometimes do. There are Christian versions of ‘you’re special!’. Many churches are tempted to air-brush the call to ‘die to self’ that sits at the heart of the Gospel.

Of course we have to ‘connect’ with where people are by showing what true Gospel flourishing looks like. But eventually the desire to flourish must be pointed down the path of self-denial. That is God’s way. So we need to be careful about ‘piggy-backing’ onto our feel-good culture with a feel-good Gospel.

Q. The so-called “prosperity gospel” has been widely criticised but continues to have a huge influence. Is this theology an example of the promotion of ego?

A. Absolutely yes. It appeals to our desires to ‘be more by having more’. Of course the Scriptures do promise that, in the long run, in the end, we truly flourish and prosper (in the broadest sense of that word) when we walk faithfully in God’s ways. But this flourishing sits uncomfortably alongside the easy promises of the prosperity gospel – because it always comes by way of the Cross.

Q. How does Grace give us the right view of ourselves and of God?

A. Because God’s grace is unconditional. The self-esteem movement was correct in its diagnosis: self-worth can’t be built on achievements, or other people’s approval, because these are ‘contingent variables’ outside of your control. They go up and down. But it was wrong in its prescription – ‘believe in yourself, you say how much you are worth’.

There’s no evidence this works because in the end it’s just your own propaganda. Self-worth needs to be rooted in identity – an inner story about who we are, where we come from and what we are for. God’s grace not only confers this identity, it comes to us unconditionally in love.

Learning how to inhabit our identity as God’s children is a life-long journey. ‘My identity in Christ’ is easy to say, but hard to learn and to ‘live’. In my book I talk about various ‘techniques’ such as ‘judge the achievement not the person’ but in the end, it grows out of a life long deepening of the conviction that we are eternally loved by our creator: unique bearers of the Divine Image called to go out and make more of his world.

ABOUT GLYNN HARRISON

Glynn Harrison (a husband, dad and grandfather) was formerly Professor and Head of Department of Psychiatry, University of Bristol, UK, where he was also a practising Consultant Psychiatrist.

His main areas of academic research were in schizophrenia and psychoses, health service evaluation and epidemiology. He is a past President of the International Federation of Psychiatric Epidemiology and acted as an advisor to WHO. His clinical passion was for early intervention in psychotic disorders. Left untreated, these are among the most devastating and potentially long term disorders in psychiatry.

Glynn speaks widely on issues at the interface between Christian faith and psychology, neuroscience and psychiatry.

Read more about by Glynn Harrison by visiting his personal website. You can also follow him on Twitter.

Published in: Evangelical Focus - family - “Our culture of selfism is producing more narcissism and fragility”